Do You Know Etaoin Shrdlu?

This 1956 ad for A&P showed terrific prices, but not-so-terrific proofreading.

Chances are that you deal with Lorem Ipsum on a regular basis. But you’ve probably never met his second cousin, Etaoin Shrdlu.

Allow me to introduce you.

Etaoin Shrdlu was born of the Linotype machine. Before Macs, before PCs, before Adobe Suite and Aldus PageMaker, there was the Linotype. This behemoth (approximately two tons of metal standing about seven feet tall) was invented in Baltimore in the middle of the 1880s by a German clockmaker. His name was Ottmar Mergenthaler, and his revolutionary machine reigned supreme as the typesetting solution for about 100 years.

Ottmar Mergenthaler c. 1912.

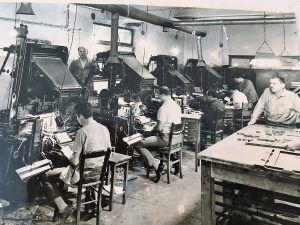

A Linotype operator at work at the Swedish Tribune, Seattle, Washington, February 1904.

Lots of Linotypes, c. 1950.

The Linotype was a radical improvement over setting type by hand. (Thomas Edison, apocryphally, called it the eighth wonder of the world.) Rather than having to gather minuscule pieces of type, one letter at a time, and arrange them meticulously in a composing stick (a portable type holder), a Linotype operator would simply press keys on a keyboard, brass molds of letters would fall into place, and the machine would form a beautifully justified “line o’ type” using a molten lead alloy.

I’ve heard that this liquid metal was 550ºF; I’ve heard it was 530ºF. I can confidently say that it was frighteningly hot, especially on those occasions when, due to misaligned matrices (molds of letters), it would suddenly spew out toward the unfortunate operator.

Linotype keyboard. Copyright 2006 Marc Dufour for Wikimedia.

The Linotype keyboard was not the “qwerty” situation we’re all accustomed to. On this 90-key arrangement, the uppercase keys sat on the right side and the lowercase keys on the left. And—rather brilliantly, if you ask me—the keys were arranged according to how commonly they were used. The first column of both the uppercase and lowercase sets, from top to bottom, were e, t, a, o, i, and n. The second row contained, from top to bottom, s, h, r, d, l, u. (Keep these most-common letters in mind for the next time you play Hangman.)

There was no backspace on a Linotype. No delete key. And certainly no screen to identify any mistakes you might make. You just had to proceed with extreme attentiveness, caution, and dexterity.

To err is human, however. When a mistake was inevitably made, all that could be done was to remove the bungled line in its entirety. This would happen when all the slugs (pieces of lead) were assembled and arranged for the press. So if the Linotype operator noticed he’d made a goof while typing (chances were better than 95% that the operator was a man), he’d call attention to that goof. To convey, “There’s a mistake here,” he’d give the line the ol’ etaoin shrdlu treatment. He’d run his finger down the first one or two rows of keys, which would spell out “etaoin” or “etaoin shrdlu.” That was the red flag that commanded, “remove this line.”

Well, as we all know, publication deadlines can lead to rushing, and rushing can lead to mistakes. And sometimes, even though an “etaoin” or “etaoin shrdlu” had been thoughtfully typed out, the messed-up line would not get removed and would end up getting printed.

Readers came to notice these bizarre inclusions, and “etaoin shrdlu” earned something of a mythical status. The two words have been used to name characters in books, comics, and music.

I thought it would be fun to hunt down these words in the wild. So, using the Library of Congress’s “Chronicling America” collection of digitized newspapers, I searched for the word “etaoin” in print during the Linotype years. I found countless examples. Here are just a few—each offers its own anachronistic charm.

An ad in the El Paso Herald, 1911.

A bit blurry, but worth squinting for so you can see how far your real estate dollar went in Omaha in 1911. Also, Potato Cave would be an excellent name for a band.

From La Sentinella (Port Chester, NY), 1923. Italian! “Etaoin shrdlu” transcends languages.

So, if you’ve ever accidentally left a bit of “lorem ipsum” text in a layout, know that you are part of a long history of such oversights. And feel a connection to the remarkable Ottmar Mergenthaler and his wondrous typesetting machine.

Check out this clip from Linotype: The Film for more on etaoin shrdlu.

etaoin shrdlu from Linotype: The Film on Vimeo.

This article was last modified on May 7, 2020

This article was first published on November 11, 2019

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Previewing Separations and Flattening

Claudia McCue shows how to use the Separations Preview and Transparency Flattene...

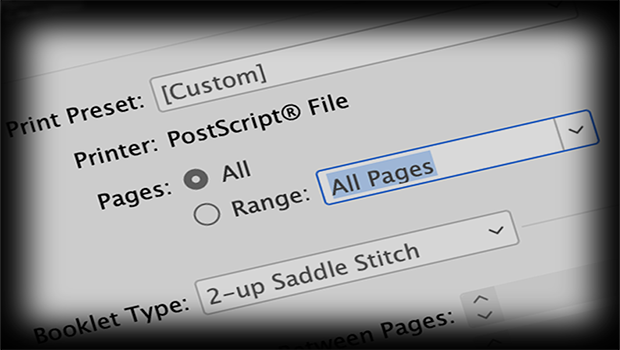

Creating a PDF from InDesign’s Print Booklet Feature

A step-by-step guide to creating a PDF of printers spreads with Print Booklet.

Creative Folding for Every Budget

Whether you’re a high roller or watching every penny, you can find an eye-catchi...