The Ultimate Guide to Kerning

Even the smallest of spaces can have the biggest impact on the appearance of type. Here’s how to always get it right.

This article appears in Issue 75 of InDesign Magazine.

Even the smallest of spaces can have the biggest impact on the appearance of type. Here’s how to always get it right. Have you ever been reading something, innocently absorbing information, when you come across something that just doesn’t seem right—like a word that looks more like amica when you expected to see arnica? Or dang when you expected clang? You’re not alone—you’ve just experienced a Kerning Problem. Kerning in the digital world refers to the addition or reduction of space between two specific characters, often referred to as a kern pair. Kern pairs are necessary to balance the white space between certain letter combinations in order to create even typographic color and texture as well as to optimize readability. The term kern originated in the days of metal typesetting, when a kern was the part of the metal type that overhangs or extends beyond the body (or “shank”) of the metal type (or “sort”) so that it could rest on the body of an adjacent character, allowing for closer spacing and better letter fit. Although kerning originally referred to the cutting away of the body of the sort, “to kern” type came to mean the removal of space between two characters, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Left: 72-point Garamond Italic metal type demonstrates the large space between the unkerned lowercase s and an apostrophe. Center: An s kerned by cutting away the side of body, or shank, resulting in an overhang that will sit atop the apostrophe sort. Right: A lowercase p cast with the kerning of the descender, which now extends off the sort. Photo by Ray Nichols of LeadGraffiti.

Now back to today: in a professional-quality digital font, each character is spaced to

create optimum overall fit with as many characters as possible. The spacing of a character consists of the width of the actual glyph plus the space that is (most often) added to the right and left side (also called “sidebearings”) in order to keep the characters from crashing into each other when typeset. (Visualize this as an invisible box around each character consisting of the character plus the space on both sides.) But due to the quirks of our Latin-based alphabet (and many others as well), there are many combinations that don’t naturally fit together well and need adjustments. Therefore, kern pairs of both positive and negative values are built into a font to improve its overall spacing. A high-quality font can have thousands of built-in kern pairs, but this alone doesn’t mean it will look good. Note that if you place the cursor between any two characters and look at the kerning field in the Character panel, any built-in kerning values will appear in parentheses (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Default kerning values are displayed in the Character panel when you put your type cursor between two characters.

If a typeface isn’t spaced well to begin with, it will need many more kern pairs than a properly-spaced font. In addition, if a font is sized much larger than its intended range—like setting a body text font at a large display size—the spatial relationships between the characters can optically change and appear uneven, necessitating some additional custom kerning to balance out the negative spaces between some letter combinations.

The Principles of Custom Kerning

The goal of kerning, as well as of proper letter fit in general, is to create an even sense of typographic color, texture, and balance between all characters. In order to achieve this, all character pairs should theoretically have the same volume of negative space between them. I stress theoretically as this is not actually possible with all character pairs, but it is a good place to start in order to understand the goal of good kerning and of spacing in general. Another way to help visualize this principle is to imagine pouring sand in between each pair of characters: every space should theoretically have roughly the same volume of sand. This might sound easy to achieve, but in reality it can be difficult, if not impossible in some cases, due to the idiosyncrasies of the individual characters. Here are some important guidelines when considering custom kerning: Proper kerning begins with an under-standing of the spatial relationship between straight-sided characters, such as H or l, and rounded characters, such as O (Figure 3). There are three basic classes of character relationships:

- Straight to straight: requires the most open space of the three

- Straight to round (or round to straight): slightly tighter spacing than straight to straight

- Round to round: slightly tighter spacing than straight to round

The operative word here is slightly, as round-to-rounds are often over-kerned by those unfamiliar with proper kerning principles. (And of course, many characters are a combination of straight and round shapes, such as b, d, g, p, and q.)

Figure 3: These three relationships are essential to understand in the execution of proper kerning: straight to straights are one distance apart, straight to rounds (and vice versa) are slightly closer, and round to rounds are slightly closer than that.

Like, or similar, neighboring shapes should have like, or similar, spacing. That is, a round to a straight character combination, such as or, should have the same spacing as a straight to a round, such as le. Serifs of straight-sided characters should not touch each other. (Neither should rounds, for that matter.) Diagonals can touch or overlap slightly, as well as some other combinations whose shapes create large negative spaces, but it’s a question of taste, not a hard and fast rule (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Rounds should never touch; nor should the serifs of straight-sided characters, as shown in the upper example. The lower image illustrates the proper relationships.

Strive for visually even negative space between all characters. Don’t over-kern. “Less is more” when it comes to proper kerning. When in doubt, go without… custom kerning, that is. Consistency is critical! When kerning, review your work often to make sure you maintain consistent negative spaces, especially between the same or similar characters (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The two RA combinations are spaced differently in this example of inconsistent kerning. Although both are acceptable solutions, they should look exactly the same.

You can train your eye to see spacing more acutely by observing character shapes and their spacing all around you—in magazines, book covers, posters, packaging, menus, logos, and so on. Some find it helpful to turn the type upside down to more easily see the special relationships without being distracting by reading the actual words. Others like to squint their eyes so they can see the “gray” of a word or phrase. Just as musicians practice their instruments, or athletes practice their sport, observing your surroundings with a critical eye will help you to do your job with more finesse. You’ll learn to see spatial relationships that you might have trouble seeing now, which in turn will help you to properly kern your typography.

Kerning in Action

Figures 6–8 illustrate how to apply these important principles. Keep in mind that while there’s tasteful kerning and poor kerning, there’s no one single correct way of kerning, but rather a range of acceptable solutions.

Figure 6: All-cap settings can present spacing challenges. Resist the urge to jam or over-kern parallel diagonals, as well as rounds, as shown in the upper image. Keep their negative spaces balanced with the rest of the word.

Figure 7: The upper setting has inconsistent spacing between like combinations (po and og, ph and ic) as well as very open spacing between the Ty and the yp—all improved in the lower image. The Ty and the yp pairs overlap, which is acceptable with diagonal strokes.

Figure 8: You can adjust uneven word spacing as well as punctuation (upper) with the kerning feature (lower). To kern a word space, place the cursor between the character and the word space (or vice versa) and kern as you would two characters.

Try the Three-letter Approach

As previously mentioned, the goal of kerning is to create even color, texture, and balance between all characters. All character pairs should theoretically have the same negative space between them. But analyzing the spacing of many characters and/or several words at once can be overwhelming without a strategy. That’s where the three-letter technique can make the process easier. The technique goes like this: when looking at a headline or display setting, start from the beginning and isolate three letters at a time, either by blocking them off with your hand, two pieces of blank paper, or, as you become adept at it, just mentally. If you’re looking at a computer screen, enlarge the type as much as necessary to get a more accurate representation of the actual outline of the characters as well as the space between them. Just make sure you can still see the entire word. Look at the negative spaces between each pair of letters, and determine if they’re relatively even. If the negative spaces are noticeably different, you might need to open or close one or both letter pairs. But before you make any changes, use the three-letter technique for the entire word or several words to get a feel for the rhythm, flow, and balance of the headline (Figure 9).

Figure 9: The three-letter technique makes it easier to identify unbalanced character pairs, which can then be opened or closed for a better overall result.

The optimum overall spacing depends on the typeface (serif, sans, and overall design characteristics) and on the intended size of the actual type. Once you get a sense of the overall rhythm of the spacing, begin to open or close some of the worst spacing. Then step back, take a look, and go through the process again, adjusting as much as necessary to create even typographic color. Print out the type often during this process for a more accurate representation. Note that certain character pairs, such as Ty and rk, always have a lot of negative space between them. Don’t over-tighten them, and don’t use them as a guide for the rest of the character combinations. Once you become adept at this technique, kerning a headline will undoubtedly become faster and easier, and you will be able to kern without fear. Remember, when it comes to custom kerning, don’t err on the side of overdoing it. Kerning too many pairs too much—especially before one develops a trained eye—can be worse than not kerning at all. In most instances, less is more, especially until your eye begins to see the spatial relationships between characters more easily and accurately. In time, your eye will become highly trained, and fine-tuning type will become second nature to you.

Metrics vs. Optical Kerning in InDesign

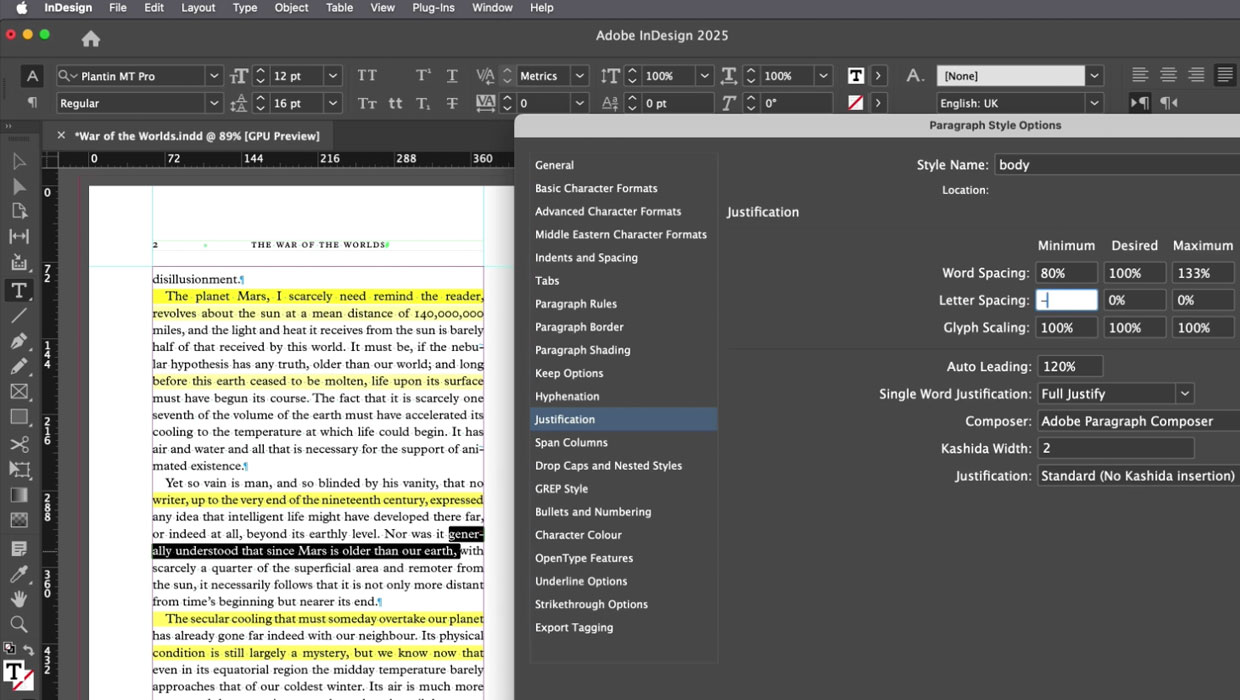

InDesign has two options for controlling automatic kerning: Metrics and Optical (Figure 10).

Figure 10: InDesign’s kerning features can be found in the Character panel and the Contol panel.

The Metrics setting, which is the default, uses a font’s built-in kerning pairs. If the font has adequate kern pair tables (as do most professional-quality fonts from reputable type foundries), this setting is usually the best choice, especially for small body text. The Optical setting, on the other hand, overrides a font’s built-in kern tables, and replaces it with values determined by an InDesign algorithm based upon the character shapes. This can be useful when a font has few or no built-in kern pairs, or when the overall spacing seems uneven. However, the real value of the Optical setting is that it automatically adjusts the letter fit when you combine different fonts, or different sizes of the same font (Figure 11).

Figure 11: InDesign’s Optical kerning, used for the Wi combination only (the rest of the word looks fine), improves the spacing between two different typestyles and sizes, although it might still need some tweaking.

To apply Metrics kerning

- Select text, or insert the text insertion point between the characters you want to kern.

- In the Character panel or Control panel, choose Metrics from the Kerning menu.

To apply Optical kerning

- Select text, or insert the text insertion point between the characters you want to kern.

- In the Character panel or Control panel, choose Optical from the Kerning menu.

Adjust kerning manually

- Place an insertion point between two characters.

- Either use the Character panel’s Kerning drop-down menu to select a preset or to insert a value, or, my preferred method, use the keyboard command (Alt/Option+Left Arrow or Right Arrow). Note you can change the default keyboard kerning increment of 20/1000 em to a smaller value for more control; this is located under Preferences > Units & Increments > Keyboard Increments (Figure 12).

Figure 12: You can change the default keyboard kerning increment to a smaller value under Preferences > Units & Increments > Keyboard Increments.

In Kernclusion

In closing, here are a few final things to remember when you’re kerning text:

- Both Optical and Metrics kerning can be selected from within style sheets.

- You can combine Optical and Metrics kerning in any given setting.

- If you change fonts or versions, be sure to double-check the type’s spacing, as what looks good for one weight or version might not look good for another.

- And ultimately, no matter which settings you use, don’t be afraid to add manual kerns as needed. The more you practice, the more you’ll develop an eye for kerning and the result will be better looking type in your documents.

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Certiport Holds Worldwide Design Competition for Students

Oh, look! Another design competition! Everyone can just relax, though, because t...

Ten Tips for New Web Designers

For those of you who may be less familiar with the details of web design it can...

Members-Only Video: How to Set Great-Looking Body Text in InDesign

Learn all the essential tips and techniques for setting great-looking type in lo...