Multilingual Publishing

Tips and tools for working in any language in InDesign

This article appears in Issue 17 of CreativePro Magazine.

Many people start to break a sweat whenever a client or boss asks them to incorporate foreign languages into their layouts. When you hear this, should you head for the hills or should you dive in, add some tools to your toolbox, and expand your capabilities?

It sounds like a no-brainer to me that you would want to expand your tools, as we are living in a fast-paced publishing world where the competition is fierce and the budgets are tight. Being able to work with multilingual projects is a valuable skill that will open up new opportunities for you. So, let’s get started!

Setting Expectations

Before I show you the tools and scripts and other magical methods of multilingualism, let me set correct expectations.

Technically, nothing is stopping you from typesetting hundreds of pages in various languages, given the capabilities that Unicode operating systems, OpenType fonts containing more glyphs than you can shake a stick at, and our beloved InDesign have to offer. But there are perils. Unless you are a native speaker of said language(s), you might be setting yourself up for the shortest customer-supplier relationship ever.

Consider a few tips:

Choose your language wisely. Though all languages will provide challenges, some languages are just easier to handle than others. Russian can be typeset in InDesign without any additional tools or scripts. Although Arabic may look intimidating at first, it is actually relatively easy to work with. Languages like Chinese and Hindu are on the more difficult side of the spectrum, and Japanese is—well, let’s just say you don’t want Japanese to be your inaugural language in the world of multilingual publishing.

Work with a proofreader who is a native speaker. Russian may be easy to work with in the sense that it does not require any tools other than a good OpenType font with the necessary Cyrillic characters, but it also has some specific requirements that InDesign does not handle very well. As such, when working with languages, it’s vitally important to have a good proofreader who is a native speaker and reader of the language. They can help ensure you don’t make costly mistakes. After all, if you have no idea what you are putting on the page, you won’t know if InDesign is doing a good job of breaking and hyphenating.

Start small. Though you may technically be able to lay out hundreds of pages in a foreign language, it is probably best not to dive headfirst into this pool of glyphs. Dip your toe in the water first, and start small (again, with a proofreader who speaks the language). Less risk is always good.

Be prepared to use character styles. InDesign’s No Break function and language-specific character styles are essential tools in a multilingual workflow. Though GREP can help, some manual application of character styles is inevitable.

Did I mention you should work with a native-speaking proofreader? Yes, I know I did, but I am mentioning it again. Because if you don’t, you should be prepared for some tough questions from your customer. If you remember only one thing from this article, I want it to be the requirement of including a native-speaking proofreader in your process. Let the road sign in Figure 1 serve as a cautionary example.

Figure 1. This road sign was made without a native Welsh speaker proofreading the text. It’s a very funny example of what can go wrong, though I doubt the person who had to pay for the sign to be replaced was laughing. Source: The Guardian

InDesign and Regions

A quick Google search reveals that there are currently an estimated 6,500 spoken languages, of which about 4,000 also have a written form. In terms of InDesign, we can sort some of those languages into a few groups.

The “standard” version of InDesign

By default, InDesign is ready to work with left-to-right languages, which include but are not limited to these subgroups:

Western European: These languages, closely related to English, include French, Spanish, German, and Italian. Most fonts should have all the glyphs required to typeset in these languages, which use the roman alphabet and the Adobe Paragraph Composer.

Central European: Still closely related to English, these languages include Polish, Czech, Lithuanian, and Turkish. They use the roman alphabet, but they also employ a lot of glyphs with accents specific to the language (?, ?, or ?, for instance) that may not be available in every font you use. These languages also use the Adobe Paragraph Composer.

Greek and Cyrillic: Neither of these use the roman alphabet, and both have such extensive character sets that most regular fonts will not suffice. OpenType is pretty much a requirement to work in these languages, and you will also need to investigate and make sure your font of choice supports Greek and Cyrillic. These languages use the Adobe Paragraph Composer.

Indic and South-East Asian: These languages do not use the roman alphabet and include Hindi, Vietnamese, and Thai. They have extensive character sets requiring specific fonts, and they also require the Adobe World Ready Composer.

See Issue 128 of InDesign Magazine for the fundamentals of setting type in Indic scripts.

InDesign ME (Middle Eastern)

Setting type in Middle Eastern languages brings a challenging set of requirements. First, you need to use fonts with appropriate character sets, because these languages use a different alphabet comprised of Arabic or Hebrew. You also need the Adobe World Ready Composer and the ability to set text right to left.

The good news is, technically speaking, all versions of InDesign have right-to-left functionality built in. If you receive a document from someone in the Middle East, you can open that document with your “regular” version of InDesign, and everything will be rendered correctly. However, you’ll need a specific version of InDesign (the Middle Eastern, or ME, version) to actually have an interface for the right-to-left features or a third-party utility that brings them out of hiding. (We will discuss these options shortly.)

See Issue 92 of InDesign Magazine for a look at the details of working with Arabic fonts.

InDesign CJK (Traditional and Simplified Chinese, Japanese, and Korean)

Typesetting Arabic and Hebrew may make you a bit uncomfortable, but at least they still have an alphabet with a relatively limited character set. Just wait till you have to do some Chinese, Korean, or Japanese typesetting—that’s when the fun really starts!

You will very likely need additional fonts beyond what is delivered with InDesign. You will definitely need the Adobe Japanese Composer. Even though many of these languages do run horizontally from left to right, some of them may not only be vertically typeset, but also be typeset from right to left.

In other words, CJK may be the toughest of all. As with Middle Eastern languages, the requirements are very specific, and as such you will need the right set of tools to deal with them properly.

Working with Languages in InDesign

Let’s consider some of the options and tools for working with multilingual content in InDesign.

Working with the “standard” version

As I’ve mentioned, the standard version of InDesign has ample support for multi-lingual typesetting. There is one important thing to note, though: You won’t find a universal language setting in InDesign as you would in Word.

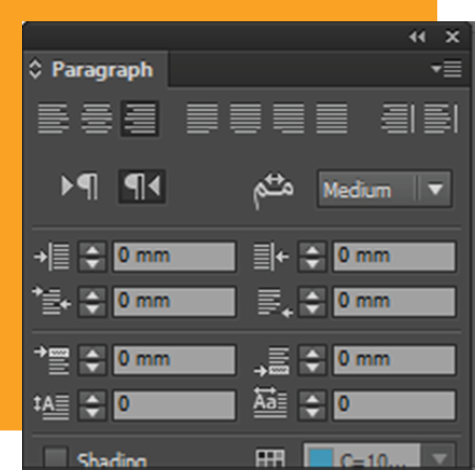

Instead, languages are defined at the character level and can be captured in either paragraph or character styles under the Advanced Character Formats option. So, please—do yourself a favor and use styles when working with multi-lingual documents!

Though I do believe a global language setting might come in handy in InDesign, one of the big benefits of language defined at the character level is that you can easily define multiple languages in a single paragraph.

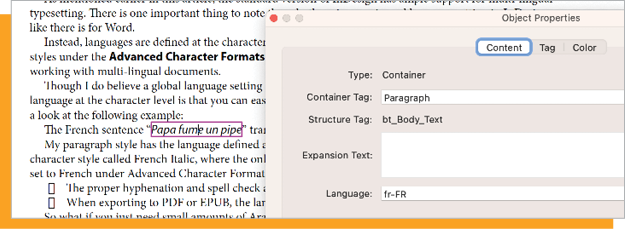

Let’s look at an example: the French sentence “Papa fume une pipe,” which translates to “Dad smokes a pipe.”

My paragraph style has the language defined as English: UK. For the French portion, I created and applied a character style called French Italic, which does only two things: It applies italic, and it sets the language to French.

This ensures:

- That the proper hyphenation and spell check will match the defined language

- That when I export my layout to PDF or EPUB, the language tag will travel through to the exported file (more on that later)

So, what if you just need small amounts of Arabic or other languages that are not supported by “standard” InDesign?

In that case, you have a couple of options. First, you could use free scripts to switch character direction. Secondly, you could copy and paste from an existing InDesign file typeset with an ME or CJK version of InDesign if you know someone who could provide that file for you.

When you need more

Based on your requirements, you have two main roads open to you.

Use a third-party plug-in: Remember that any recent version of InDesign has the core capacity to deal with composing text in other languages, but the interface offers no way of setting the required parameters. Third-party plug-ins at the very least enable these interface elements, while offering other options as well.

You have two main choices of plug-ins for working with multilingual output in Arabic: ScribeDOOR from WinSoft and World Tools from In-Tools. In terms of composing both Arabic and CJK, there’s really only one plug-in you can use: World Tools Pro from In-Tools.

Install ME or CJK versions of InDesign: Back in the day, you had to purchase separate versions of InDesign to be able to work with Arabic and CJK content. With the introduction of Creative Cloud, installing a different language version is now as easy as following five steps, outlined by Adobe in this support article.

So which road do you choose?

As is often the case, both paths come with their own advantages and challenges. If you plan to set large amounts of text in foreign languages and you use Creative Cloud, then you might be tempted to save money and install complete versions of a different language version of InDesign. That may seem to be a good idea, but be sure you know what you’re getting into.

Choosing the English (Arabic) or English (Hebrew) option installs InDesign ME, which adds options to panels and installs additional fonts, but your interface will remain in English (Figure 2). If you install Creative Cloud in Korean, Japanese, or Traditional or Simplified Chinese using the procedure outlined in the Adobe support article, you will need to set your operating system to the respective language as well.

Figure 2. In the ME version of InDesign, the Paragraph panel adds features specific to right-to-left typesetting, but the interface remains English.

For Middle Eastern languages, installing a specific version via Creative Cloud promises a relatively smooth ride, but installing CJK can be a rough road. So, in my opinion, World Tools Pro is the best option for a non-native speaker to tackle CJK publishing.

If you know you will be working with both Middle Eastern and CJK languages, you can install the complete version of InDesign ME and grab World Tools Pro for CJK. Having World Tools Pro is a no-brainer, because it offers one-stop shopping for all your language formatting needs (and doesn’t require you to learn Chinese).

This scenario might also make sense if you plan to typeset only Middle Eastern languages on top of Western European, Eastern European, Greek, Cyrillic, Indic, and Southeast Asian, which you could do with a default installation of InDesign. In that case, World Tools or Winsoft’s ScribeDOOR might still be the best choice for you.

Note: In the interest of full disclosure, I work with companies that have access to ME or CJK versions of InDesign and often have dedicated staff creating multilingual content. As such, I do not feel comfortable offering advice on which plug-in is best, since I have not used either of them. However, in researching details for this article, I got the sense that people are generally very happy with World Tools. Both In-Tools and Winsoft offer free trials of their plug-ins. Diane Burns wrote an extensive review of the In-Tools plug-ins in InDesign Magazine Issue 51.

Unicode and OpenType

Let’s take a step back and talk about Unicode and OpenType, as these standards form the foundation of multilingual publishing.

As the name implies, Unicode is an international encoding standard. It is used with different languages and scripts, and it has the bidirectional support that is so integral to Arabic and Asian languages. This standard works brilliantly to ensure that any computer system that supports Unicode shows the same symbol, be it in Word, a browser, or InDesign.

If you really dive into it, Unicode is quite comprehensive, but in essence it’s nothing more than a very big table that gives each of more than 120,000 characters an exact and unique four-character alphanumeric value. In Figure 3, you’ll see that the humble pilcrow has a Unicode value of 00B6.

Figure 3. Using the Glyphs panel to search for Unicode values: Hover over a glyph to see the Glyph ID or Unicode value.

On the website of the Unicode consortium, you can find charts that tell you exactly what value a certain character has.

Back to the other foundation: OpenType, a font format designed primarily by Microsoft with support from Adobe to replace TrueType and PostScript Type 1 formats. It was meant to have the advantages of TrueType (cross-platform compatibility and other technical stuff) while offering potential storage for a lot more glyphs: 65,536, to be exact.

I firmly believe that in this day and age PostScript Type 1 fonts should be avoided at all costs, although there are undoubtedly exceptions where you would still use them (perhaps in EPS files). For multilingual publishing with large character sets, using OpenType fonts is the sensible thing to do.

A very important warning: Just because a font is labeled as OpenType does not mean it actually contains the required glyphs for multilingual publishing! Some font foundries simply repackage a TrueType font with its original 265 characters as an OpenType font.

In other words, make sure that any font you intend to use actually contains the characters you need for the particular language you will be using. If the font is synced via Adobe Fonts, you can check its language support by clicking Details on the font family page (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Details on the Adobe Fonts website showing the languages supported by a font

Unicode Tips

Searching for glyphs: InDesign can search by name or Unicode value in the Glyphs panel; be aware that this search applies only to the font selected in the bottom left of the panel. It would be a great addition in a future version of InDesign if you could search for fonts that contain a specific Unicode character.

Finding a Unicode value: The charts on the official Unicode web pages are very detailed but also very hard to search. Though there are quite a few websites that provide searchable Unicode overviews, one of the best is unicode-table.com. Use the search feature, or scroll through the glyph tables until you find the glyph you’re looking for. Once you do, hover over a symbol to learn more about it. Then check out InDesign Magazine Issue 41, which has an article called “Tracking Down Obscure Glyphs” that provides a workaround for inserting a glyph by number. Or, you could use this free script from Rorohiko.

GID versus Unicode: Any character in Unicode has a unique alphanumeric value that represents the same character across multiple systems. The GID (Glyph ID) essentially determines the position of a glyph within a given font and as such is unique. The same Unicode character can have different Glyph IDs in different fonts, and alternate designs for the same Unicode character can coexist in the same font. For example, in Minion Pro, three versions of the close parenthesis all share Unicode 0029, but the default character’s GID is 10. The one used with numerators has a GID of 477, and the one used with denominators has a GID of 494.

Don’t Forget the Glyphs Panel

Can’t find information about your font on a website? Glyphs panel to the rescue!

To confirm whether the Glyphs panel contains the characters you need, select text in the font you wish to verify. Open the Glyphs panel (Windows > Type & Tables > Glyphs) and make sure to select Entire Font under the Show menu. If you want, increase the preview size using the icons at the bottom right. You can now see all the characters available in the font.

Also, check out Steve Werner’s great article at CreativePro.com, “How to Find the Font That Has the Glyph You Need.”

Getting Your Content Into InDesign

You now have some background knowledge about dealing with languages, so let’s take the next step and actually get some stuff into InDesign. At this point, you might think it will be really hard work, but it is surprisingly easy to get your multilingual content into InDesign. Use InDesign’s File > Place command as you normally would, and presto—you are a multilingual publisher!

Even without any third-party tools or language-specific versions of InDesign, InDesign gives you access to Adobe Fonts, which offers enough fonts to place a large portion of the text (Figure 5). From here, you can set up the correct fonts, set the correct language, and even choose the Adobe Paragraph Composer or Adobe World Ready Paragraph composer without needing any additional tools.

Figure 5. Proof you can place multilingual content quite well without additional tools

As I stated earlier, that means you can set Western European, Central European, Greek and Cyrillic, and Indic and South-East Asian languages right out of the box. You can already set the correct fonts and languages for Middle Eastern languages and Chinese and choose the World Ready composer for Middle Eastern languages. That is already a whole lot of languages!

To go any further, however, you will need additional tools. I am presuming you will be using World Tools or World Tools Pro.

No Typing or Translating

You might notice I do not talk about any other ways of getting your content into InDesign other than File > Place. There are several reasons for this.

First, using the Place command ensures the text is correctly processed by InDesign (unlike pasting, which can cause problems).

Second, typing content in Thai, Hebrew, or Hindi—though theoretically possible—is not practical at all, especially for a non-native speaker.

Third, InDesign cannot turn one language into another, just in case you had that idea. Your content needs to come into the program in the correct language to begin with.

No Typing or Translating

You might notice I do not talk about any other ways of getting your content into InDesign other than File > Place. There are several reasons for this.

First, using the Place command ensures the text is correctly processed by InDesign (unlike pasting, which can cause problems).

Second, typing content in Thai, Hebrew, or Hindi—though theoretically possible—is not practical at all, especially for a non-native speaker.

Third, InDesign cannot turn one language into another, just in case you had that idea. Your content needs to come into the program in the correct language to begin with.

Getting Your Content Out of InDesign

As designers become increasingly aware of accessibility needs, it should come as no surprise that special consideration for multilingual documents apply to material prepared for screen readers and other ways for people to access the content.

Working with PDF

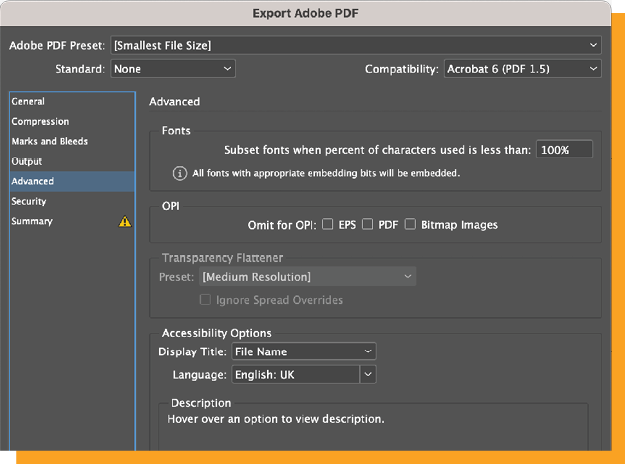

As I mentioned, InDesign does not have a global language setting like Word does. When exporting an interactive PDF or one for print, you can define such a language for the PDF in the Advanced section (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Setting a language for the export to PDF under the Advanced tab

Even so, it is important that other languages defined in the styles are still properly tagged. When exporting PDFs for digital consumption, make sure to select the option to Create Tagged PDF.

In a tagged PDF you can select an item in the Tags panel and view its properties to see the assigned language. For example, in Figure 7 you can see that the clause Papa fume une pipe has been defined as French, even though the rest of the document is English. This has huge benefits for accessibility!

Figure 7. Looking at the tags structure in Acrobat shows French assigned to this content.

Tip: For more comprehensive guidance on accessibility in publishing, CreativePro members can download our Accessibility SuperGuide.

Working with EPUB

For those of you using InDesign to create EPUBs, the language attribute also travels through to the HTML embedded within the EPUB. But unlike for PDF, there is no global setting for language when exporting to EPUB, yet InDesign does embed a language tag in the <body>. I have not found the logic Adobe uses to determine the <body> language.

As with PDF, the sentence in InDesign with a portion defined as French is exported to EPUB with that language specified at the character level: <p class="bt_Body-Text">The French sentence "<span class="French-Italic" lang="fr-FR" xml:lang="fr-FR">Papa fume une pipe</span>" translates to “Dad smokes a pipe”.</p>

A special note about InDesign 2023

In InDesign 2023 (v18.0) Adobe made some small, undocumented tweaks to the export of EPUB which resulted in every single paragraph now having a lang attribute and people getting validation errors like:

Error while parsing file: value of attribute “lang” is invalid; must be an RFC 3066 language identifier.

Fortunately, in version 18.1, the validation errors have been fixed.

Multilingual = Multiplied Opportunities

Producing multilingual content is not necessarily more difficult than producing content in your native language. The foundation for many languages is available in InDesign, technologies such as Unicode and OpenType make it relatively easy to handle different characters, and with a small investment you can expand the language support greatly.

Naturally, you’ll need to learn about the details of a new language, and—have I mentioned this?—it is absolutely vital that you have a native speaker of the language to proofread your content before you deliver it to your customer.

Let’s be honest: You very likely won’t be able to produce long documents without some practice. But the next time a customer asks you to incorporate multiple languages into a project, you will be able to weigh the pros and cons and expand your business!

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

InDesign Magazine Issue 136: Advertising

We’re happy to announce that InDesign Magazine Issue #136 (August 2020) is now a...

Tips for Multilingual InDesign Projects

Learn how you can help your InDesign translation process go as smoothly as possi...

InReview: MindSuite Pro

Master collection of linguistic products includes grammar checking, a thesaurus,...