Out of Gamut: Why Is Color

The Observer

Remember: The different wavelengths of light aren’t really colored; they’re simply waves of electromagnetic energy with a known length and a known amount of energy. It’s our perceptual system that gives them the attribute of color. Our eyes contain two types of sensors — rods and cones — that are sensitive to light. The rods are essentially monochromatic, with a peak sensitivity at around the 510nm wavelength: They contribute to peripheral vision and allow us to see in relatively dark conditions, but they don’t contribute to color vision. (You’ve probably noticed that on a dark night, even though you can see shapes and movement, you see very little color.)

The sensation of color comes from the second set of photoreceptors in our eyes — the cones. Our eyes contain three different types of cones, which are most properly referred to as the L, M, and S cones, denoting cones sensitive to light of long wavelength, medium wavelength, and short wavelength, respectively. It’s tempting to make the gross oversimplification that the cones are sensitive to red, green, and blue. Certainly, the fact that we can combine the primary colors (red, green, and blue) to make a huge range of other colors is due to the three types of cones in our eyes, but the cones are a lot more complex than sensors with RGB filters.

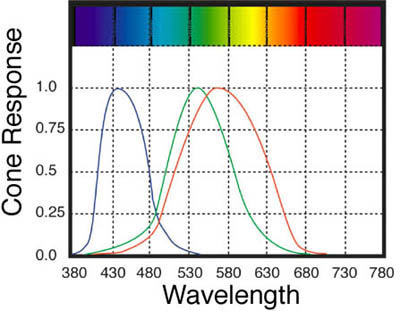

Figure 4 shows the cones’ raw sensitivities to differing wavelengths, and also shows why labeling them R, G, and B would be a gross simplification. The horizontal (x) axis shows wavelengths, and the vertical (y) axis depicts the intensity of cone response to each wavelength. There’s a great deal of overlap between the M and L cones, and a small region where all three responses overlap. For example, a pure wavelength of 480nm will stimulate all three cone types. A wavelength of 580 nm stimulates the L cones slightly more than it stimulates the M cones.

Figure 4: From left to right, the curves above show the sensitivity of the S, M, and L cones to various wavelengths of visible light.

Moreover, the cones respond to light in a complex manner; they aren’t like the sensors in a scanner or digital camera, where each sensor simply records the amount of light it receives. Rather, the cones in our eyes feed into a processing system that not only receives the signal from each cone, but also compares each signal to that of its neighbors, and assigns weighting to the raw signals. One reason such weighting is necessary is that we have many more L and M cones than S cones. The relative population of the L, M, and S cones is approximately 40:20:1.

Red, green, and blue work well as primary colors for monitors, scanners, and digital cameras, but due to the overlapping responses of our cones, we can’t create wavelengths that would act as primaries for our eyes, stimulating only one cone type. Mathematically, however, such a set of theoretical primaries is possible, provided we allow ourselves the unlikely luxury of creating “negative light” that can subtract itself from one cone type while stimulating another. A model based on just such an approach forms the basis for all our current color-management systems.

CIE 1931 Standard Observer

In 1931 the Commission Internationale De l’Éclairage (CIE) — the international standards body that deals with all aspects of light (and hence color) — created a mathematical model that uses synthetic, imaginary primaries that represent the individual cone responses. These primaries are labeled X, Y, and Z. Though mathematical constructs rather than physical realities, the CIE primaries model behavior that is very real.

If mathematical trickery makes your eyes glaze over, don’t worry: The key point to understand here is that this model represents the way our eyes receive continuous spectra as stimuli, and convert those continuous spectra into varying amounts of three different primaries.

A second important point is that, while it’s true that each individual’s color perception is to some degree unique, this model aims to represent the color perception of an individual with “normal” color vision — dubbed “the CIE 1931 Standard Observer,” and decades of testing have shown that it does so very well.

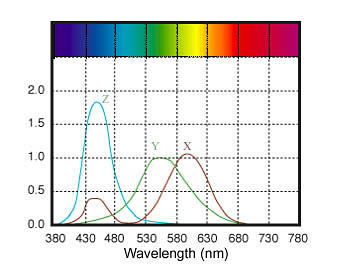

Figure 5 shows the response of the CIE 1931 Standard Observer, which represents “normal” color vision. Unlike spectral measurements, which use values for each band of wavelengths, CIE XYZ represents colors using three values.

Figure 5: The CIE 1931 Standard Observer represents the color perception of a “normal” person. The curves show the intensity of X, Y, and Z values (akin to cone response) for a given wavelength.

We don’t typically interact with CIE XYZ directly, but CIE XYZ lies at the heart of all current implementations of color management: In short, CIE XYZ and its close cousin CIE LAB (derived from CIE XYZ) define well-known, light-independent, device-independent color spaces that software, device profiles, and drivers often use when interpreting or translating color information.

If you care to understand the principles of color management, the most important thing to note about the 1931 standard observer is that each of the three responses covers a wide band of wavelengths, and that there is considerable overlap. The implication is that samples with different spectral response curves — samples that reflect or transmit different amounts of energy in the visible portions of the spectrum — can appear the same color, by creating the same response from our eyes’ cones. For instance, let’s say the light reflected from one object comprises multiple wavelengths that each cause a gentle response from the M cones. Another object with a different spectral composition might match the overall M-cone response with a narrower band of wavelengths that individually cause a sharper reaction.

This article was last modified on July 18, 2023

This article was first published on April 25, 2001

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

How to Link Text Between Two InDesign Documents

Find out how to link text in one InDesign document to a completely separate docu...

Moving Text From Word to InDesign

While some InDesign users focus on getting great-looking graphics into their lay...