Designing a Product Layout

Organizing chaos with white space.

This article appears in Issue 134 of InDesign Magazine.

An image-driven layout is a staple of lifestyle magazines: a roundup of products arranged over a page or spread, with a brief description of each and information about how they can be purchased. These designs seem simple—until you try to create one yourself. Often the simplest layouts are the hardest, so in this article, I’ll provide some fundamentals to help you build this kind of image-driven layout.

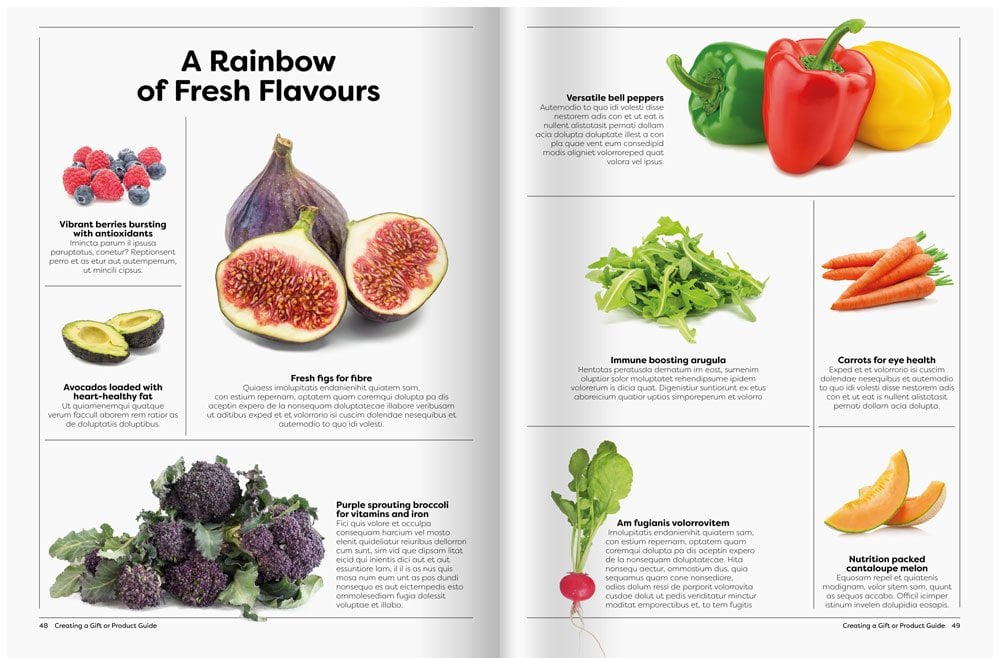

To begin, step away from your computer for a moment. As always, I suggest that you start by researching how others have solved the design problem. Look through magazines you may have for inspiration, or browse the magazine racks at your local bookstore, newsstand, or library. Ask yourself what worked well (and what didn’t) in the designs you find, then build on what you liked by adding your own nuances and style. You should, of course, do the same with this article’s example layout (Figure 1).

Figure 1. What we’re aiming for

Image Treatment

Now that you’re full of inspiration, let’s start by preparing your images in Photoshop. To maximize the use of white space and give the layout an airy feel, you’ll want to silhouette the images. The irregular shape of the images is key to providing visual interest. Although it’s okay to include a couple of conventional rectangular images, if you go overboard with them, the layout might look staid and static. Because you’ll be cutting out the subjects from their backgrounds, make sure the images you choose are not cropped. Ideally, they should be shot against a white or contrasting color background, making it easier to mask them in Photoshop.

Be sure to include any area where the subjects cast a shadow in the

selection to provide some dimension. With the Quick Selection tool active, choose Select Subject in the tool options, refine the selection if necessary, and then convert this to a layer mask. With a soft brush paint in white on the layer mask in the foreground of the subject to reveal the shadow—or as much of it as you want (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Use fixed color sample points (A) in conjunction with the Info panel (B) and a Levels adjustment (C) to ensure that any unmasked white areas are indeed pure white. Mask the background with a layer mask (D), but paint back in the shadow cast by the object (E).

Use Photoshop’s Info panel to verify that the white of the background is a pure white (R 255, G 255, B 255). It can help to put down color sample points, using the Eyedropper tool with the Shift key. If necessary, use a Levels adjustment layer to force any light grays to pure white.

Yes, getting the images ready in Photoshop can take a lot of time, but it’s worth it to be precise at this stage and avoid unpleasant surprises later.

Document Setup and Layout Grid in InDesign

With the images ready, switch to InDesign and create a two-page document. Because you want a spread, turn on Facing Pages and make sure your first page is an even-numbered page. (Even-numbered pages begin on a left page in most languages.)

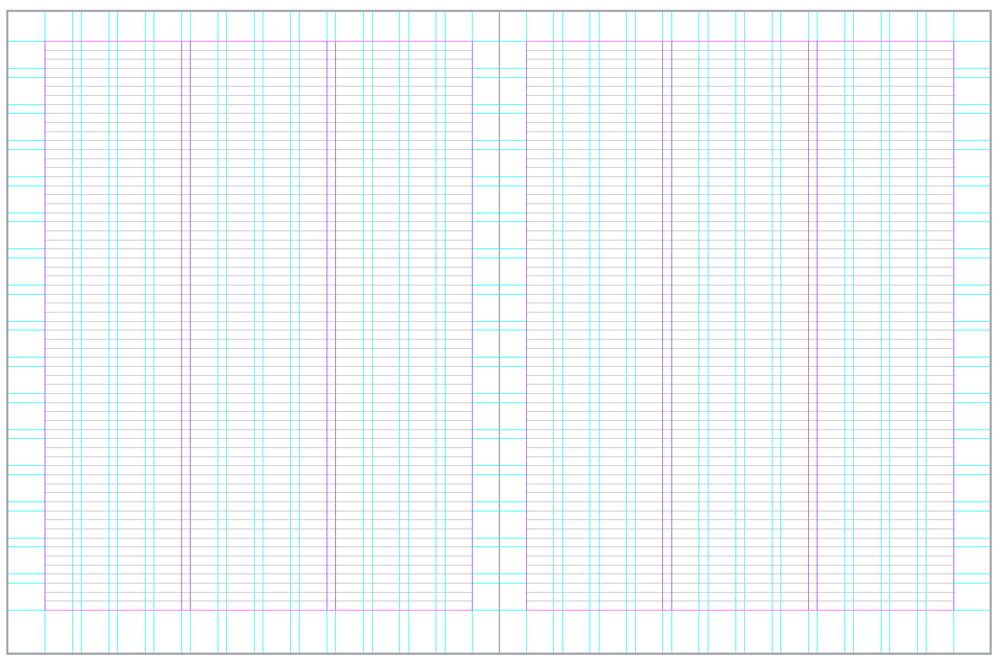

A layout grid will help you to organize the information. The number of grid subdivisions you use is partly a matter of personal preference. For the example, I opted for 12 columns and 16 rows—a combination that provides much flexibility, but also comes with the potential visual confusion of having many grid lines (Figure 3). At its core, this is a 3-column layout, with the larger items occupying 2 columns and the smaller items a single column. A 12-column arrangement is divisible by 2, 3, 4, and 6, making it malleable to your needs and also suggesting layout opportunities.

Figure 3. The layout grid, together with the baseline grid, helps structure the content and suggest layout options. Should it become too restrictive, you can always break it.

Balance and Image Placement

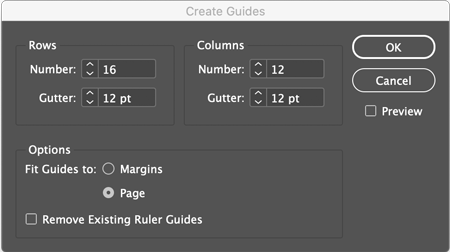

Design is largely about leading the reader’s eye to where you, the designer, want to take it. Images often have a sense of direction: where it looks like they’re pointing. With faces, this is easy, but with vegetables, it’s more subtle. The images should face in—towards the spine—rather out to the edge of the page. Notice the green pepper stem and larger crown of broccoli point inward. This makes them sit comfortably within the composition rather than looking like they’re trying to escape the page. The spread is balanced with a large image at bottom left and a correspondingly large image at top right, leading the reader’s eye diagonally up and around the spread (Figure 4). To introduce an element of mischief, some images break out of the grid or even bleed off the edge of the page.

Figure 4. Placing a large image bottom left and another top right leads the eye down from the large, bold headline around the spread.

Just because you’re using a grid to organize your content, doesn’t mean you necessarily want the reader to notice it. Irregular image shapes help downplay a grid’s linearity. Combining the organic shapes with the structured nature of the page allows you to create a layout that is fun and dynamic but gives up nothing in terms of hierarchy and readability.

Type Choice and Treatment

In an image-driven layout, the type plays a supporting role to the imagery. It does so in a way that is unobtrusive while at the same time quietly firm about the hierarchy of information. To reinforce this, bold subheads contrast with a lighter weight of the body text in the example. I chose a sans-serif family, Filson Soft, in keeping with the minimalist aesthetic of the spread. Although many sans-serif typefaces are neutral, Filson has a lot of personality. Its rounded quality makes it appear friendly, and it has a particularly eccentric uppercase R (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Filson Soft is rounded for friendliness and has a distinctive R.

Most designers insist on consistency in type treatments, but sometimes being flexible can help your cause. Here, the type alignment is fluid—sometimes left, sometimes centered, sometimes right—with the text “leaning in” to its associated product, helping establish the visual connection between each item and its description. While long passages of center- or right-aligned text are seldom advisable, it works here because the descriptions are short and because the alignment plays off the position and shape of its associated picture.

Take care to craft the text with forced line breaks (Shift-Return) or judicious application of the No Break formatting, both to improve readability and to provide pleasing shapes. For paragraphs that are centered, aim for a chandelier shape. It’s important that these paragraphs look intentionally centered, rather than almost left aligned or justified. Similarly, with right-aligned paragraphs make sure your intent is clear—while at the same time avoiding lines that are very long or very short. When working with short bursts of text like these, keep hyphenation turned off.

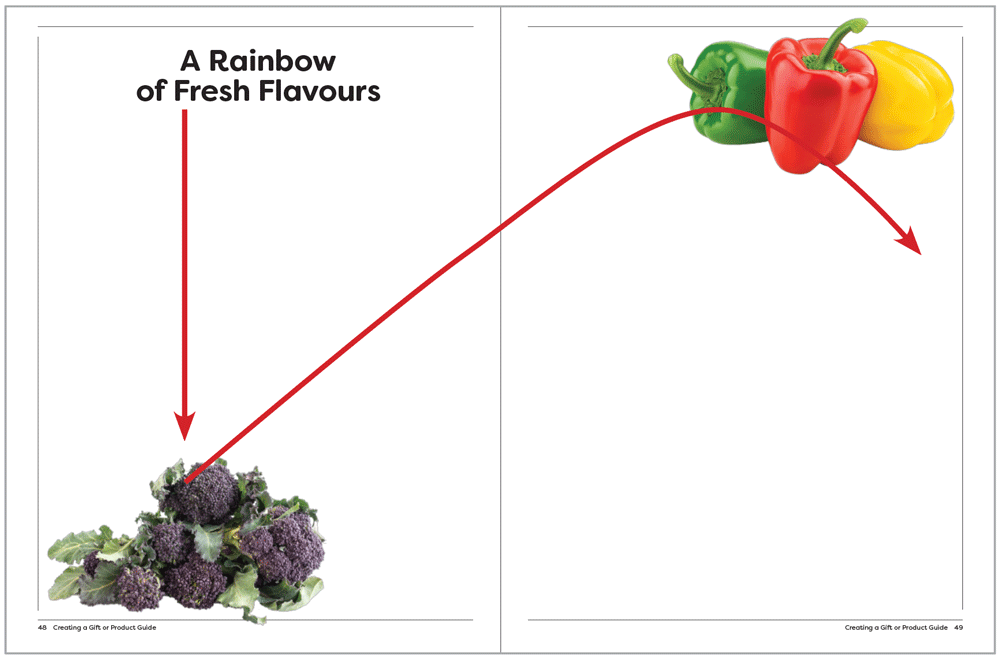

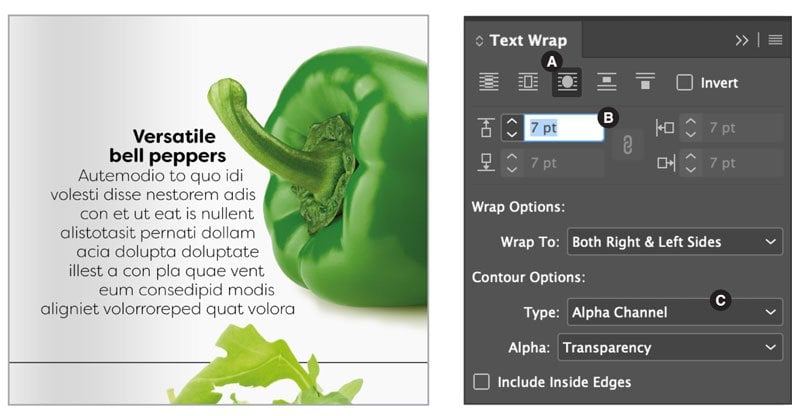

To create an interplay between image and text, wrap the text around the image (Figure 6). Make sure to keep the text readable. Watch out for any bad word spacing that might occur due to the columns being narrowed. Also, don’t overdo it. A subtle wrap on one edge of the text is often all that’s needed.

Figure 6. To allow text to wrap around a cut out image, select the picture frame and choose Wrap around Object Shape (A). Set the offset amount (B). From the Contour Options choose Alpha Channel (C) to use the shape of the layer mask added in Photoshop to create the wrap shape.

Make sure the baselines of type in side-by-side columns are aligned and that they finish on the same line, providing a solid foundation to the spread. To do this, you can employ a baseline grid, although with a limited amount of text, you can also do it by eye.

Even though there are only three styles of paragraph, it’s crucial to use paragraph styles: Not only will it make the formatting faster in the first instance, it will give you the creative leeway to make global adjustments to the spread by editing the style definitions thereafter.

Column Rules

The example layout relies upon the tension between chaos and organization (Figure 7). While the images want to bust out of their allotted space, the column rules tie the composition together and remove any ambiguity about which piece of text accompanies each image.

Figure 7. Experiment with staying mainly within the grid for a more subdued look (top) versus scaling up the images, causing them burst out of their grid fields and interact with each other (A). In some cases the images overlap the columns rules (B), causing the text to wrap around their shapes (C), and even sit behind the text (D).

Recent versions of InDesign allow you to add column rules between multiple columns of a text frame. But in this case, because each item is independent, you’ll need to draw the column rules manually. To prevent moving them by mistake once they’re in place, add them to their own layer, which you can then lock. Optionally, create an object style for the rules, so you can easily change the weight or line style globally should you need to do so.

Parting Thoughts

Ultimately it’s about the images. Because you want cut outs, select images with interesting shapes, that are easily to isolate, and with their edges in focus. It is the air in the layout that will draw the reader’s attention. The text is there to support the images, not the other way around; if no one notices its understated elegance and subtlety, then it’s doing a good job.

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Tip of the Week: Gridify Magic

This tip was sent to Tip of the Week email subscribers on November 19, 2015. Sig...

InQuestion: Numbering Headings and Synchronizing Text Frames

Erica Gamet recounts the best Q&A from the InDesignSecrets Facebook group.