Considerate Color

With a little extra care you can choose effective colors for the broadest possible audience.

This article appears in Issue 11 of CreativePro Magazine.

As part of my education in color management, I developed a keen interest in color vision deficiencies. In the late 1990s, I was astonished to hear a color expert claim that 12% of men don’t see red and green correctly. I didn’t know if the number was accurate, but it seemed extremely high.

I ultimately learned that my instinct was right: Only 4% of men don’t see red and green correctly, but even so, that number still alarmed me. For years I quoted this statistic, but eventually I discovered that was also incorrect. The reality is that about 12% of the total population—that’s all of us—do not see color correctly.

In 2016, I wrote a paper about color vision deficiencies, and—more importantly—about how graphic designers can build color palettes for people who see color this way (Figure 1). This article includes some information from that paper, which you can download in full here.

Figure 1. Teaching Considerate Color Design for People with Color-Defective Vision (13 pp. PDF) is a scholarly look at issues related to accessible design and color. You can download it from CreativePro.com.

As designers, we seldom take into account the fact that a significant percentage of our viewers cannot see color well enough to distinguish between two colors in a design. It is a disservice to those viewers to proceed without consideration. Conversely, it is thoughtful when a designer goes to the trouble of creating a color palette that can be seen effectively by everyone, regardless of their visual capabilities.

The Origins of Color-Defective Vision

Color-defective vision is hereditary: The male carries one chromosome for color vision, and the female carries two. When a child is conceived, their capacity to see color is determined by the roll of the dice where the mother gets two turns and the father only one. The genetic probability of color-deficient vision depends on whose chromosomes are passed on to the child.

Researchers have developed an accurate understanding of the numerous genetically- caused defects found in human vision and have mapped both normal human color perception and a range of color defects. In general, people may be unable to differentiate easily—or at all—between red and green, or between blue and yellow (Figure 2). Some people have no color perception at all (achromatopsia).

Figure 2. A comparison of the color wheel as seen with normal vision (left) vs. deuteranopia (right)

The underlying cause of color vision problems is indicated in the name of each condition with different word suffixes: opia and omaly. Those defects ending with opia (deuteranopia, protanopia, and tritanopia) describe people whose eyes lack color sensors (cones) of a specific sensitivity. Those defects ending with omaly (deuteranomaly, protanomaly, and tritanomaly) describe people with color sensors, but whose sensors are defective. These defective sensors vary significantly from a very small degree of insensitivity to total insensitivity. This explains how some people have a mild form of color-defective vision while others have severe color-defective vision.

Making Design Communicate to Everyone

As a graphic artist, you must be sensitive to what readers can and cannot see. If color is—by itself—a communication element, then as a designer, you have a societal obligation to be sure that the colors you use can communicate effectively to all.

For example, consider maps. If the traces on a map are printed with appropriately chosen colors, the person with color deficiencies can still see the difference between the A-Train’s routes and the B-Train’s routes and not get on the wrong train.

I live in Munich, and I admire the public transportation maps here. I enjoy their clarity. But I was recently standing on a subway train studying the map on the wall when I thought about my fellow humans who don’t see color correctly.

When I got home, I tested the Munich subway map with some excellent software, Color Oracle, which temporarily adjusts the colors on your screen to simulate how people with color vision deficiencies would see what you’re looking at (Figure 3). It’s available for both macOS and Windows and is free.

Figure 3. With Color Oracle installed, you gain a new menu bar item (top) that you can use to change the colors on your screen from their normal appearance (above left) to what they would look like to someone with various types of color-deficient vision, including deuteranopia (above right).

I discovered that the local subway map is virtually unintelligible to people with color vision deficiencies! Its design makes use of too many red and green solid colors in differentiating the various train routes (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The rainbow of colors on the Munich subway map (top) is much harder to make sense of when the reader has deuteranopia (bottom).

Designing with Colors for Accessibility

Cartographers Dr. Bernhard Jenny and Nathaniel Vaughn Kelso, who wrote the Color Oracle software, have coauthored an excellent paper on cartography for people with color-vision deficiencies. For maximum clarity in maps, they offer advice about several color combinations that can be indistinguishable to some, and they recommend using dotted and dashed rules so that the viewer need not rely on only the color of the routes (Figure 5).

Figure 5. By varying attributes such as width, hue, saturation, annotation, and line pattern, you make elements much easier to distinguish for people with color-deficient vision.

Deuteranopia is the most common color vision defect, affecting about 4 percent of men and 1 percent of women. Knowing this, I devised a technique for choosing colors distinguishable by people with that condition, using the Color Picker in Photoshop with the Lab color model (Figure 6).

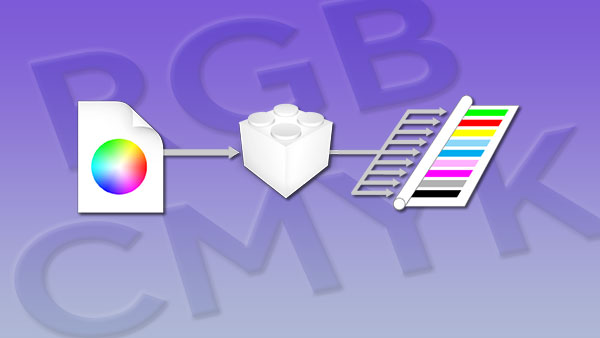

Figure 6. Picking colors in Lab mode in the Photoshop Color Picker

Lab (technically, L*a*b*) is the largest color space available in Photoshop, and it is the color space that Photoshop uses when you convert between RGB and CMYK spaces. Unlike those color spaces, Lab is device-independent, because it literally describes what the color looks like, not how to make it with ink or light. You can convert your images to Lab if you want to, but you don’t need to convert your image in order to use Lab mode in the Color Picker. You can define color swatches in Lab and then use them in any Photoshop (or InDesign or Illustrator) document and they’ll automatically be converted to the document’s color space when you apply them.

To define considerate colors for people with deuteranopia, start by dragging the L channel slider near its upper limit. Click in the top half of the color field (the big square) to select a color, then click Add To Swatches.

Next, click in the lower half of the color field to select a color and add it to swatches. Together, your two new swatches form a pairing of considerate colors for people of all vision types (Figure 7).

Figure 7. To pick pairs of contrasting colors for people with Deuteranopia, use Lab mode and choose one color from the top of the field and the other from the bottom half.

If you see an alert icon next to the New Color box in the Color Picker, that means your color is out of gamut for the document’s color space. Click the small box below the alert to have Photoshop choose the closest in-gamut equivalent. Or, you can drag in the field and keep your eye on the alert; when it disappears, you have an in-gamut color.

Once you create your palette of considerate colors, you can create an ASE file that the other Creative Cloud applications can open: Select the colors, go to the Swatches panel menu, and choose Export Swatches For Exchange. Or, as you’re mixing your colors with the Color Picker, click the Add To Swatches button. In the resulting dialog box, turn on Add To My Current Library to save the swatch to a Creative Cloud Library that you can share with your colleagues (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Add your new colors to a CC Library to share with your colleagues and use in your other Adobe Creative Cloud applications.

A Few Minutes of Effort Makes All the Difference

One in eight people do not see color correctly. To ignore 12% of your audience by choosing colors without consideration of their needs is unfair. It takes only a few minutes of effort and a willingness to be a more considerate designer. Your designs will be more successful, and your audience will appreciate the effort—and it’s the right, and considerate, thing to do.

Complementary Color Content

For more essential advice and tools related to color and accessibility, see Colleen Gratzer’s article “Seeing the Benefits of Accessible Color” in Issue #149 of InDesign Magazine.

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

TypeTalk: Mastering Type and Color

Next to the actual words themselves, color is one of the most powerful tools in...

Tip of the Week: 5 Color Tricks

Sign up for the InDesign tip of the week to get a new tip, roundups of new artic...

What’s the difference between RGB and CMYK printing?

Artists and designers are taught the conventional wisdom that design for digital...