Under the Desktop: How Safe Is Your Password?

When configuring a new Web site the other day and creating its various accounts and authorities, I was reminded of the importance of passwords. We use them everyday for professional, financial, and recreational purposes. Yet, how often do we consider the importance of our password(s) and their security? If you’re like most content creators, not much. Or ever.

Think how many passwords you enter on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis: to access information sites on the Internet; to open your financial records; to connect to your clients’ remote servers; to get money out of your ATM. All these services are vital to your business and digital lifestyle.

At the same time, passwords are more than the means to gain access to these services. On the Internet, you are your Web site and e-mail. What would it mean to your branding if someone messes up the content on your site or uses your computer for nefarious purposes? Or sends out messages under cover of your name and account?

No good, for sure.

Inside a large corporation with a professional IT department, the account managers act as password cops, mandate the use of complex passwords and require users to change passwords on a regular basis.

Outside, many creative folks just use a single, simple password for all their digital accounts. And that’s bad news. Many of us just enter our pet’s name, or our birth date.

However, when we work outside of the gaze of such watchful yentas, we must shoulder the responsibility ourselves for our own password security.

So what makes a good password?

All the Ones and Zeros (and Special Characters)

Before describing the elements of a good, secure password, it’s useful to understand the different means that password hackers, also called "crackers," employ to break passwords.

You would be surprised at the number of online cracking resources; for example, Password Crackers offers "independent information about cryptosystem weakness and password recovery" — in other words, the latest programs and resources for the cracker community. There are many such sites.

Cracking software takes several approaches to attacking your passwords: brute force, dictionaries, and mixtures of the two. Each password we create must defend against all the methods arrayed against it.

Brute force is self-explanatory. Crackers use software that tries lots of different combinations of letters and numbers, until the correct password is entered. As you can imagine, a short password will be discovered quickly with this method, especially if the password is made up only from numbers. There are just only so many combinations with a set of 10 characters.

"An all-numeric password is way too weak," agreed Ron Hipschman, Webmaster and network manager at the Exploratorium Museum in San Francisco. "Software running on an old Sparc [Unix workstation] can do 20,000 to 25,000 guesses per second. An all-numeric password with six digits can be cracked in minutes."

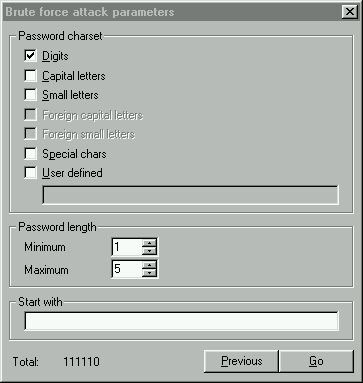

According to a review of the Ultra Zip Password Cracker software (see Figure 1), a 3-character numeric password was broken in 35 seconds.

Figure 1: This cracker software offers various settings for a brute force attack. Here the user can click in a checkbox to expand the parameters of the attack with capital letters, special characters or even a user defined text string.

Thus one way to defend against the brute force method is to add characters to the password, thus expanding the possible combinations that must be tried. At the same time, it also helps to expand the set of characters used in the password; for example using a long string with numerics, letters, and even punctuation marks.

In addition, cracking software can use dictionaries to guess words, names, or even combinations of words. These dictionaries — much like specialty dictionaries for your word processor — are widely available on the Internet and come with between 100,000 to 200,000 entries each.

These dictionaries cover lingo in different professions, names, characters in any famous text (like the Bible or Shakespeare play), or popular field of interest, such as movie titles and characters, science fiction characters, and place names, to name just a few. Hence, your password must avoid anything in the dictionary or any dictionary, even in a foreign language.

Of course, many of us think we’re being very smart by adding a single numeric digit before or after a word, or capitalizing a word. These cracking programs can also run routines on the entries that counter those moves, such as reversing words.

Hipschman said it’s also important to avoid personal information, including phone numbers, birth dates, family members, and pet names. These items are can be easily uncovered by casual acquaintances or from the Internet and then used against you.

Finding a Good Password

Despite the array of cracker resources, it’s possible to create effective passwords. While no password is foolproof, you can make things very difficult by following the following simple guidelines.

According to Hipschman, the best password should be a long, random string of ASCII text, a combination of lower- and upper-case characters, numbers, and punctuation. He admitted, however, while this makes it impossible for a dictionary program to find your password, it’s almost impossible for anyone to remember. Most likely, you’d write it down, which is also a very bad thing to do (more on that later).

Instead, it’s important to find a password that’s easy to remember but hard to guess. And the longer the better. Some Unix systems put limits on length, but 6 characters should be the minimum. Eight or more is preferred.

To make a password that’s easy to remember, security mavens suggest using a two-word (or more) phrase divided by one or more punctuation marks. It should include upper and lower characters. For example, the phrase "wild man" becomes "wiLD#mAn" or something similar.

Many people change the letter "L" to the number 1, or an "S" to a 5. This practice is on the right track but these obvious alphanumeric analogs are now well understood by crackers. It’s best to use punctuation marks instead, which because they are also completely out of context, improve defenses against dictionary attacks.

An alternative is to take a longer phrase and then create an acrostic using the first letter of each word or each syllable. For example, the case of the musical cow(a Perry Mason mystery fist published in 1950) could become "tcO&tM#c."

For my own passwords, I take a phrase and misspell each word, which also makes the password harder to crack (and to make even more sure, one is also a misspelled foreign word). For variety, I create different sets of passwords using other misspellings special characters. I then rotate these passwords throughout the year.

Antisocial Engineering

There are other ways that crackers can uncover your passwords, beyond the software already mentioned. They include so-called social engineering and Trojan Horse programs.

Social engineering is a non-technical attack. Instead it uses human nature and psychology against the victim. Here the cracker calls on the phone and pretends to be a technical support representative or some other trusted person. They then will attempt to persuade you to reveal your password.

Sometimes the cracker will send an e-mail message asking for the same information. Or search around your desk to see if you’ve written down your password and account information on a Post-It note. In addition, they will instead ask you to change your password.

So, never give out your password to anyone. And don’t write it down. Or change it on the request of someone claiming to be a system administrator needing to make repairs.

Meanwhile, Trojan horses are small applications that you’re tricked into running; they’re often disguised as innocent e-mail attachments. Some of them are malicious, performing bad things to your computer or other computers on the network or even over the Internet. In addition, some Trojan horse programs that can store your passwords and then relay them to the cracker.

"Security is a matter of vigilance," Hipschman offered." You have to keep up with patches as well as secure passwords."

To prevent Trojan horses, be sure to keep current with security updates for your operating system and Internet applications.

Security is serious business and serious for your business. Still, it’s a sad situation. As the Talmud reminds us: "Deception in words is worse than deception in money." In the case of password cracking, you get both.

Read more by David Morgenstern.

This article was last modified on January 6, 2023

This article was first published on February 27, 2003

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Third Party Solutions for Data Publishing

Yes, InDesign can be used for creating data-driven publications, such as catalog...

The Benefits of Online Proofing for the Creative Workflow

The volume and speed of creating and approving marketing collateral have become...

Get Your Print Answers Now at New PrintingForLess.com Help Center

Would you like to get answers to your print questions from the convenience of yo...