Scanning Around With Gene: When Printers Went to War

Editor’s Note: We recognize that some of you will feel strongly about this article. We encourage you to express yourself in the Vox Box on the left-hand side of this page or by writing to ed****@*********ro.com. The sentiments expressed in this article are not necessarily those of creativepro.com or of its parent company, PrintingForLess.com.

Memorial Day is the United States holiday meant to honor soldiers killed in war. Last May 29, while looking at the newspaper inserts suggesting that the way to honor our war dead is to shop, I started thinking about how isolated we’ve become from the impacts of war. The people dying in Iraq are just as dead as those who died during World War II, only this time we Americans are not being asked to make sacrifices (unless you count being hated by the rest of the world). So there are no daily reminders of the consequences of war, no paper or ink shortages, no rationing, no community efforts to round up scrap metal for gun making — and no visible support for war from the business community. Just our President telling us over and over again about the threat of “the terrorists,” and our usual arrogance toward people and places we don’t fully understand. I wondered if someday future generations will look at “Terrorist Day” as a great time to buy a new car or that extra-large stainless steel grill.

Indifference and ignorance weren’t always the case, of course, and the graphic arts industry was once a vital supplier of war goods and a key player in the propaganda fueling public support of war. I know this because I used Memorial Day as an excuse to look through a decade’s worth of Graphic Arts Monthly magazines. These issues, dated from 1941 to 1950, show just how involved everyone was in the war effort and what a huge impact the war had on industry. It would be nearly impossible, it seems, to be indifferent about war in those days.

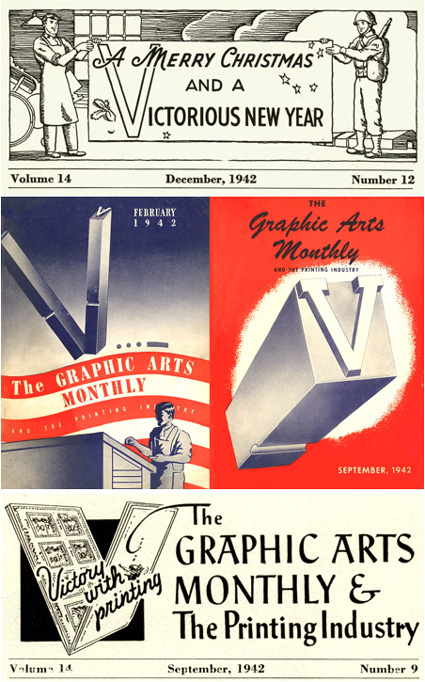

Figure 1. The Graphic Arts Monthly has always been one of the leading printing industry publications. During the World War II years, the magazine often ran patriotic covers and other material, including a series of covers reflecting a “V for Victory” theme. These examples are all from 1942.

It’s a little sad to me that our industry no longer involves itself in the issues of the day, preferring instead to use our powerful tools almost exclusively for profit. In America, anyway, the old saying about “the power of the press” is not nearly as relevant as it once was, and most people would no longer agree with Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle when he said in 1857 that “the three great elements of modern civilization are gunpowder, printing, and the Protestant religion.” During World War II, however, that statement rang true.

Figure 2. In showing support for the war, press manufacturer Chandler & Price ran this ad highlighting the virtues of truth. The copy goes on to say: “Truly truth is mankind’s door to freedom — the printing press the key to that door.”

The printing press was indeed a weapon of war, used as masterfully by Hitler’s propaganda machine as it was by small resistance movements in towns throughout the world. I have a very romantic notion of secret printing runs taking place in the middle of the night, of soldiers marching into town to confiscate printing presses, and of printers scrounging bits of mismatched metal type to produce provocative handbills.

Figure 3. Citing the French underground resistance movement, Chandler & Price said in this ad that “the printing press, since its origin, has been the one indestructible weapon in man’s struggle for freedom.”

Shifting Manufacturing Resources

Not only were the presses and metal type of the day important communication vehicles, but the companies that manufactured graphic arts machinery and supplies were vital elements in the conversion of industry to the war effort. In America, the major machinery manufacturers turned over most, if not all, of their manufacturing capacity to weapons or other needed goods to supply the war effort.

Figure 4. In 1941 the Craftsman Corporation advocated buying quickly, before supplies ran short. Indeed, it appears from other articles in Graphic Arts Monthly that many printers did upgrade just before the United States joined the war effort.

Printing businesses back at home were advised to “make it last” and given lots of information about proper oiling and maintenance of existing equipment, for it was clear there would be no new printing presses delivered for quite some time.

Figure 5. Metal, rubber and other resources were in short supply during World war II, so many ads and editorials were focused on conservation and the need for sacrifices among business owners. Many companies, such as the Brackett Stripping Machine Company, used advertising space to explain why it would be hard to buy new equipment or parts for older equipment.

The graphic arts industry had to learn to get along not just without new machinery, but without metal for type casting, paper and ink for printing, and other goods. Fiber board for packaging was particularly hard to come by, so many goods were shipped in re-usable containers.

Figure 6. In this 1942 Graphic Arts Monthly editorial, R. Randolph Karch tries to dispel the idea that printing is wasteful and should be curtailed whenever possible to save resources. By using racist cartoon images, he hoped to shift blame to the enemies, even though he admits in the text that the printing industry is, indeed, unnecessarily wasteful. If racism were a necessary component of national pride, maybe we’d be better off without it.

Government regulations required that printers stock only 90 days’ worth of materials, that old type galleys be re-melted, that presses and other equipment not in service be scrapped for re-use, that paper not contain as much bleach or other whitening agents, and more.

Figure 7. One consequence of war was a shortage of the chlorine used to bleach paper to a bright white. In the ad that accompanies the illustration (top) from Champion Paper, the copy says “Chlorine is much less necessary for bleaching pulp than for war essentials to bleach the bones of dictators.” Gilbert Paper took a slightly less dramatic stance (bottom) in explaining why it was simplifying paper lines.

Of course, every industry pitched in during those days, and the tone of most advertising was that of “we’re all doing our part,” even if it meant going without and a substantial slowing of business. The good news for printers was that the United States government was dramatically expanding its printing needs (estimated at $20 million in 1942). The bad news was that many business uses for printing dropped dramatically during the war years as everyone focused on essentials.

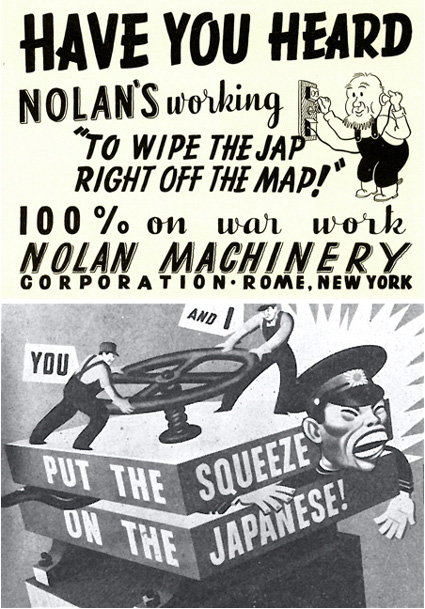

Figure 8. Nolan Machinery (top) was a major supplier of proofing devices and other printing equipment. During the war years the company switched to manufacturing items for the Army, and used its advertising space to post strong, often racist political messages. A racist pro-war poster from RCA (bottom) was featured in a 1942 article highlighting the war-related work of printers. Not all aspects of national unity are desirable — sometimes enemies are reduced to offensive stereotypes.

At the same time that these rules and regulations were limiting printers’ access to supplies, the graphic arts industry was encouraged to use the power of its presses to produce posters and other materials supporting the war. In one printing newsletter, the editor said, “You can make your printed promotions a slap in Hitler’s face by showing a defiant and constructive picture of America at work to win the war.” And an editorial in Graphic Arts Monthly of May 1942 suggested that “there should be no minimization of the part played by the graphic arts in finally beating the Axis powers to their needs.”

One way the industry did this was by promoting the purchase of war bonds, a government-sponsored effort to raise much-needed cash by selling securities directly to the American public. By the end of the war, over $185 billion worth of war bonds were sold, promoted almost exclusively through donated advertising. Printers supplied the stock cuts and appropriate artwork, often without charge, that local advertisers, newspapers, and other publishers used to promote the sale of war bonds.

Figure 9. One check on marketing priorities is to look at what the stock photo and clip-art companies are offering up. During war years most of them promoted the availability of patriotic and pro-military imagery.

In 1942, there was even an effort by the printing industry to raise $400,000 by having each of the 40,000 printing establishments in the United States send in $10. The money was to be used to purchase two bomber planes for the government, which would be named by the printers who contributed. The effort fell short, however, and no “Gutenberg Bombers” were deployed. I’m not sure how the printing industry in America dealt with the irony that most major printing developments had taken place in Germany, but I can say that “buying American” was a popular theme in industry advertising at the time. You didn’t see a lot of ads for Heidelberg presses in 1942.

Figure 10. H.B. Rouse & Company makes a vague connection in this ad between military might and the effectiveness of its band saws, despite no direct connection. Every company wanted to appear supportive of the war effort.

Figure 11. A cross hair may seem like an odd way to promote Christmas and Thanksgiving paper stock, but it just shows how closely associated with the war effort everyone wanted to be.

And though American manufacturers didn’t make as much profit selling presses and supplies to the United States military as they would to the printing industry, there was a strong market for equipment as field printing plants were set up around the globe and on Navy ships. Returning military printers would, in fact, become a primary pool for labor after the war as the printing industry returned to normal.

Figure 12. Press manufacturer Chandler & Price explained in its ad (above) that the shortage of new presses was due to large orders from the military to equip ships and field operations. And American Writing Paper Corporation (bottom) promoted its papers’ durability through battlefield references.

Were Times Really that Different Then?

World War II may have been an exception in the way it brought nations together (and split some apart). And in the 1940s print played a much more important role in vital communications than it does today. But it’s still hard to imagine a situation today where printing, let alone any industry, would get involved in political or social issues, fearful of being politically incorrect. (I did find one Web site where graphic designers can contribute anti-war artwork.)

The printing presses of all nations are still a potential tool for social and political change. But for an industry to make a difference, there has to be passion on the part of the owners and workers. In America, the destruction of printing unions, the consolidation of printing businesses, and the general lack of guts on the part of industry leaders has resulted in a bland and ineffective industry. The printing press is no longer looked at as a vehicle for free speech, but as an expensive manufacturing unit that must be kept busy regardless of the political or artistic consequences.

I’m not sure what it will take to get Americans united in their attitudes toward the war in Iraq, but I don’t think it will be due to any effort on the part of the graphic arts industry.

I dream of the day when more young people figure out that new technology, like text messaging and podcasts, can be a catalyst for social change, just as the printing press once was. I just hope it happens before the death count in Iraq gets much higher.

Gene left 11 images on the scanning room floor. To see these outtakes, go to page 2.

This article was last modified on May 18, 2023

This article was first published on July 14, 2006

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

CreativePro Tip of the Week: Resetting the Bounding Box of Objects in Illustrator

This CreativePro Tip of the Week on resetting the bounding box in Illustrator wa...

Using Photoshop’s Plastic Wrap Filter

Photoshop’s Plastic Wrap filter is great at creating liquid effects of all...

Turning an Image to Pure Black and White in Photoshop

Turning images to black and white gives them a stark, urban feel that can look g...