Scanning Around With Gene: Back When Typesetting was a Craft

Last week I mentioned that I’m cleaning out my library, and took a look at some books on paste-up and page composition. Today I’m featuring images from a classic book on photo-composition written by John Seybold, who (along with his son Jonathan) was legendary in the typesetting industry and produced a widely-read newsletter that chronicled the transition of composition from hot metal all the way through to modern desktop publishing. Because the book is signed and because of its importance in the history of a field I loved, I’ve decided not to throw this particular volume out, but will put it in a box in the garage along with some other typesetting memorabilia I’ve held onto over the years.

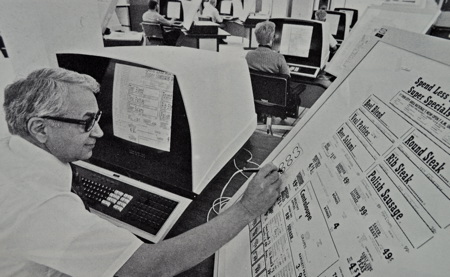

The book Fundamentals of Modern Photo-Composition was published by Seybold in 1979 and represented the state-of-the-art of how type was produced and pages composed using specialized computer-driven machinery. Looking through the book was a trip down memory lane for me – I worked on many of the machines pictured here over the years when I was a typesetter. This was back in the pre-Macintosh days when typesetting was a unique job that required training and a bounty of special skills. Click on any image for a larger version. The third picture below is John Seybold at the keyboard.

Typesetting was both fun and frustrating back in those times – nearly every bit of copy had to be re-keyboarded (there was no Microsoft Word), so typesetters had to be, first and foremost, good typists. In fact, as you’ll see below, many of the early typesetting machines used typewriters as the keyboard input device.

I came into the business before computer memory was a common commodity – we stored our work on punched paper tape that you would physically store with the job in case anything had to be run again (which it almost always did). Paper tape was a unique experience – the sound of the tape punching caused quite a racket, and you new you were really serious when you could read the characters on the tape based on the punch pattern.

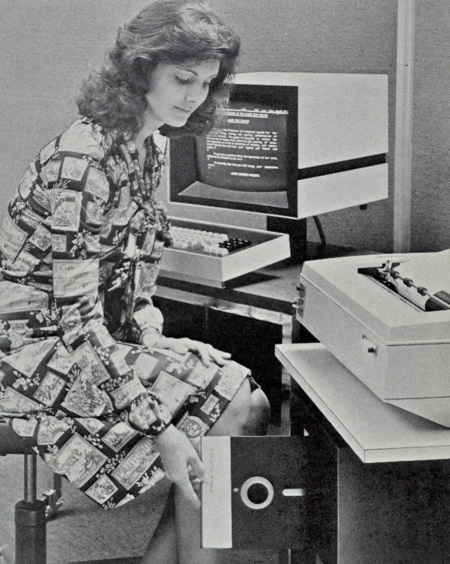

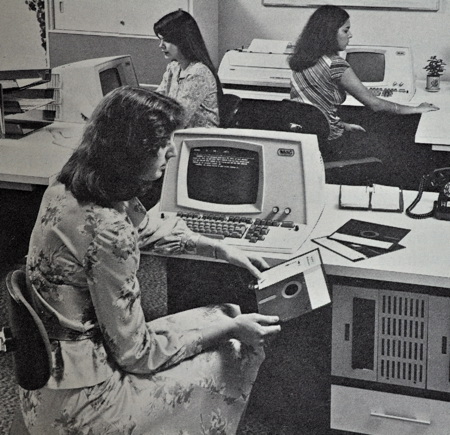

It was a real breakthrough when keyboards started being paired with cathode ray tubes so you could actually see what you were typing. Some of these keyboards were “blind” – you didn’t know where line endings were happening or whether type would actually fit. All you could do was put in a line length, point size and other attributes and hope for the best. You would find out quickly when you ran the tape through the typesetting machine just how well you did. I worked on all three of the machines below – a Mergenthaler CorrectTerm, and AKI Ultra Count, and a Compugraphic 7200, which set large headline type.

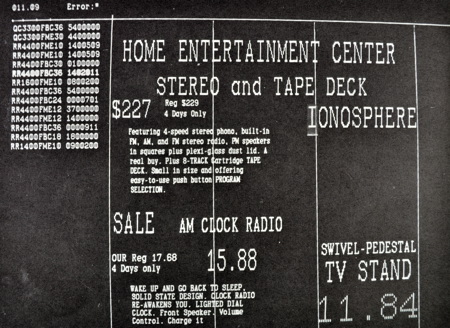

As I said, screens were pretty “dumb” back then – the best you could hope for was a rough approximation of the actual type output. There was certainly no “what-you-see-is-what-you-get” technology that we’ve now become so accustomed to.

It was a real boon when typesetting machines started getting magnetic memory capabilities – you no longer needed to re-type things when they didn’t come out right or the photo paper got eaten by the processing machine. Memory came, at the beginning, in two forms – 8-inch floppy disks and cassette tapes.

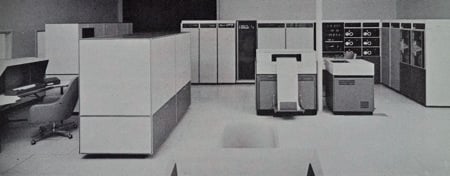

Eventually they developed hard drives to store even larger amounts of copy, but it was expensive. I remember paying nearly $4,000 one time for a 64 Kilobyte memory upgrade. Here is an early multi-platter hard drive.

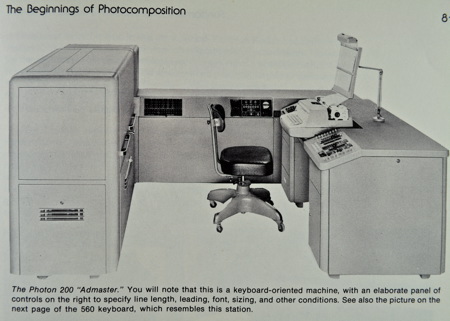

Eventually computers got more sophisticated and various companies introduced larger systems that could actually compose graphic items in place like borders, reverses, etc., not just type. These units enjoyed a relatively short period of popularity as they came out just before the Macintosh and PostScript changed everything.

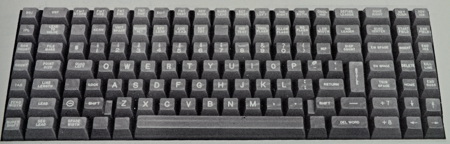

I don’t miss all that much about the photo-type era, though some of the machines were fascinating pieces of technology with lots of moving parts and ingenious ways to get type on a piece of paper. But one thing I do miss is the keyboards themselves, which typically had many more keys than today’s units. There was a key for all the various commands and you didn’t have to learn keyboard shortcut combinations. If you wanted to change leading, point size or line length, there was a key for that.

Plus, the other thing I miss about this era is the typesetters themselves. Being a typesetter took a certain personality and disposition. You were constantly dealing with “designers” who could be difficult, and fighting technology every step of the way. Sometimes getting out a few lines of type would bring you to your knees. I often say that I learned to curse being a typesetter – it was just part of the process. That and heavy drinking.

Of course things are much better now and everyone is pretty much a typesetter. There is still room for craftsmanship though (which is often lost today) and fortunately the mechanics have all been worked out smoothly. But for a while typesetting was the Wild West of computing technology and it was very exciting to be part of it.

This article was last modified on February 28, 2021

This article was first published on September 21, 2012

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

How to Straighten Photos Taken at an Angle

It’s hard to photograph many images head-on. For example, if you try to shoot a...

Heavy Metal Madness: Content Management by the Pound

Some people choose hobbies that serve as antidotes to their work selves —...

Turning Grayscale to Color in Photoshop

When it comes to creating multitone images, it’s common to think of using the Du...