Previewing Separations and Flattening

Claudia McCue shows how to use the Separations Preview and Transparency Flattener Preview in InDesign to find potential printing problems long before your job goes to press.

This article appears in Issue 67 of InDesign Magazine.

Fellow printing aficionados, it’s time to show a little love to a couple of unsung heroes in InDesign—the Separations Preview panel and the Flattener Preview panel. They may not look fascinating, but think of them as detectives that can help you find problems, long before your job goes to press.

About Color Separations

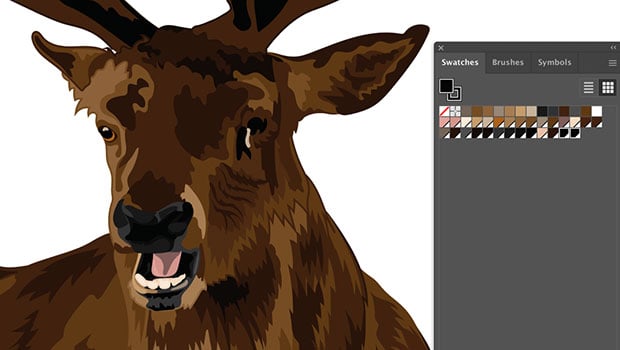

In printing, the term color separation refers to the process of separating a color image into the four process printing colors—cyan, magenta, yellow, and black, corresponding to the inks to be used on press. In the Olden Days, skilled camera specialists accomplished this with an arcane combination of colored filters and complex exposures. Now, we usually rely on Photoshop to perform this magic (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The four process printing inks—cyan, magenta, yellow, and black—combine to create a full color image when the job is printed.

Separations Preview Panel

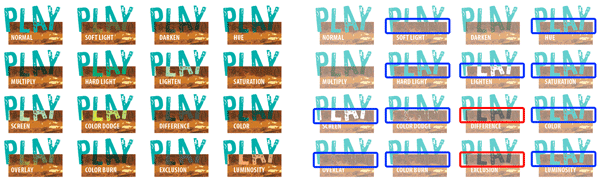

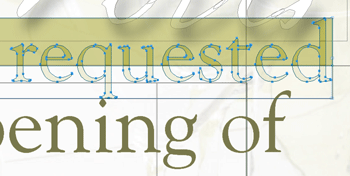

You’re just designing pages in InDesign, not running a printing press—what do you care about color separations? Isn’t that the printer’s problem? Well, yes, color separation issues can be a problem for the printer—and that can translate to missed deadlines or extra costs for you. The Separations Preview panel can be a powerful forensic tool, helping you find such problems before they become quite expensive to resolve. Choose Window > Output > Separations Preview to display the panel, and then choose Separations from the panel’s View menu (Figure 2). When you activate Separations Preview, InDesign turns on High Quality Display and Overprint Preview, so you’ll notice that graphics are sharper and color rendering is better. (Odd tidbit: when Overprint Preview is active, frame edges disappear, but guides remain visible. No, I don’t know why.)

wp-image-109956″ src=”https://creativepro.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/psffig2.jpg” alt=”” width=”250″ height=”283″ /> Figure 2: The Separations Preview panel comes to life only when you choose Separations from the View menu.

Once the Separations Preview panel is active, use it to find common problems in your layout. For example, imported content from Microsoft Word or Excel may come in as R0-G0-B0 rather than K100. When the job is output, that text will print in something like C75-M68-Y67-K90 (depending on the color settings you’re using). Even though modern computer-controlled presses are capable of very tight register, such text will not be as crisp as solid black-only text, just because of the halftone screening (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Text in just black ink (K100) has nice clean edges. RGB text looks black on screen, but will print in four colors. And because none of the inks is 100% solid, all will be rendered in halftone dots, adding to the ragged look.

Figure 4: Turning off the Black plate should make all the black text disappear. Text that’s still visible is RGB text, and will print in four colors. This is not good.

Figure 5: Although the blue text looks the same, some of it uses the wrong spot color, PANTONE 646. Separations Preview makes it easy to find the renegades.

Maximum ink limit (total ink coverage)

- Sheetfed press, coated stock: TIC 320–340%

- Sheetfed press, uncoated stock: TIC 240–260%

- Heat-set web press, coated stock: TIC 300–320%

- Cold-set web press, uncoated stock (e.g., newsprint): TIC 220–240%

Figure 6: This publication will be printed on uncoated stock on a sheetfed press, but the red highlight shows that large areas of this image exceed the recommended 260% ink limit. The Separations Preview panel reports that the total ink at the cursor position is 284%, far beyond the ideal limit.

InDesign’s misleading display

Figure 7: The PANTONE 326 text is using the Color Dodge blending mode, which looks spiffy in normal view (left). But turn on Overprint Preview (right), and you see how this effect will really print. Aren’t you glad you checked before sending it to press?

Figure 8: Use the Separations Preview panel to get a more realistic rendering of blending modes, and to reveal which areas will print as process (indicated in red).

Other Separations Preview panel options

Figure 9: To view individual plates in their printing ink colors, deselect “Show Single Plates in Black.”

Figure 10: The Desaturate Black option in the Separations Preview panel has good intentions, but poor implementation. Process black ink is a bit weak, but it’s not this weak.

Figure 11: Set the onscreen rendering of black ink to “Display All Blacks Accurately” to more easily differentiate between K100 and rich black content.

Flattener Preview Panel

- Raster/Vector balance: The degree of vector information to be preserved. The lower the setting, the more vector objects will be rasterized.

- Line Art And Text Resolution: The resolution used in the event that any text or line art must be rasterized.

- Gradient And Mesh Resolution: The resolution used for shadows, feathers, and other pixel-based effects.

- Convert All Text To Outlines: As you might expect, this converts text to outlines. As a result, text hinting is lost, and type will look rough in Acrobat (if “Smooth Line Art” is off in Display preferences), or on low-resolution desktop printers; however, type is fine on high-resolution devices.

- Convert All Strokes To Outlines: Replaces all strokes with filled shapes, to avoid discrepancies between unflattened strokes and filled shapes.

- Clip Complex Regions: Uses object paths to determine boundaries between vector and rasterized artwork to avoid awkward “stitching” artifacts. This option can result in very complex files for output.

Previewing Flattener results

Figure 12: Highlighting transparent objects will reveal effects such as drop shadows, use of blending modes, and elements with less than 100% opacity. Keep in mind that this doesn’t mean that content will cause printing problems.

Figure 13: Because of transparent interactions, the text highlighted in red will be converted to outlines and filled with pixels. It’s not as scary as it sounds.

Figure 14: Here’s an x-ray view of InDesign’s handling of a drop shadow interacting with text. Let’s hear it for the InDesign engineers!

Forward With Forensics

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

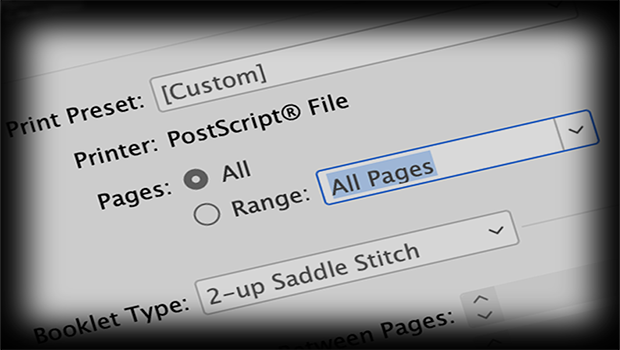

Creating a PDF from InDesign’s Print Booklet Feature

A step-by-step guide to creating a PDF of printers spreads with Print Booklet.

Preview a Mix of Color and Grayscale Pages in Your InDesign Document

With some creative uses of layers and libraries, you can create a template that...

How to Reduce Ink Density in Illustrator Files

Learn how to detect and solve potential problems with ink limits in vector art.