InType: Type That Touches

Need an impactful type design? Try breaking the rules of word spacing.

This article appears in Issue 82 of InDesign Magazine.

What happens when letters connect…or don’t

Like much in life, good typography is as much about what to leave out as what to include. That special ingredient of space between the letters plays a key role in the way we respond to a message. Often “invisible,” good letterspacing, or tracking, is a key component of readability. It requires contrast between the letters and their background. It’s the background that gives form to the type. While consistency is usually the goal, does that mean consistently tight, consistently loose—or consistently “just right?” And how do we know the difference?

Why Does it Matter?

With loose letterspacing, we see more of the background. Too much, and the background gobbles up the type—letters lose their association with each other, and words lose their shape. With tightly-spaced type, we see less background—the words can look dense, possibly more impactful. But if there’s not enough background, the letters run into each other (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The same text with letterspacing “just right” (top), too tight, and too loose.

kerning applied (left), and no kerning (right).” width=”200″ height=”144″ /> Figure 2: Common letter pairs in need of kerning. Metrics kerning applied (left), and no kerning (right).

Figure 3: A kern too far.

Aesthetics Change

Exactly what constitutes good letterspacing is neither fixed nor universally agreed upon. It varies according to the method of typesetting, the size of the type, and typographic fashion. In Ye Olde Times, when type was made of metal, the space between the letters was fixed—the spacing literally being a part of the type (Figure 4).

Figure 4: With metal type, the spacing is incorporated into each piece of metal.

Figure 5: The distinctive style of Herb Lubalin, using his signature typeface Avant Garde for the magazine of the same name. Lubalin took liberties with the traditional rules of letterspacing and leading to create tight-knit “typographic pictures,” to make the type more expressive. Of the digital reproductions of Avant Garde, only the OpenType Pro version contains the stylistic alternates necessary for producing type treatments like this.

Ligatures

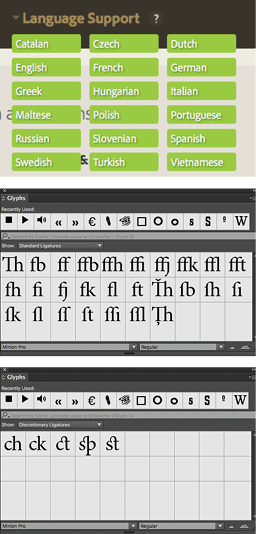

There is, of course, a subset of characters—ligatures—where the letters touching is the whole point. If fact, everyone’s favorite glyph—the ampersand—started out as a ligature, combining E and t, forming the Latin word “et,” meaning “and.” Ligatures join two or three separate glyphs into a single unit to create the visual effect of the type intentionally touching—either for the aesthetic reason of avoiding a collision of characters, for ornamental purposes (discretionary ligatures), or to simulate the joined letterforms of handwriting (Figure 6).

Figure 6: An example typeface with extensive language support, Minion Pro has a full range of ligatures.

Figure 7: Ligatures in logos and hand-drawn display type: The University of Sussex logo by Blast, and Try and Fail by Wells from the Tumblr blog “I Love Ligatures.”

Figure 8: Normal rules do not apply.

Figure 9: UK road signage: the loose spacing of the type is designed to increase legibility from a distance.

Take a Deep Breath

Tight or loose, the air you incorporate into your type is as important as the choice of type itself. A typeface’s personality will change depending on its letterspacing—the spaces around the letters functioning like intervals between notes of music. While consistency is usually desirable, when it comes to display type, even this tenet can be broken if done with bravado and confidence.

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

InDesign Template: Workbook

This template contains pages for chapters of course material, reviews, quizzes,...

Vertical master page spreads

Thanks to some Page tool magic, we van use this simple technique to create verti...

Autoflow Text when Pasting

O.B. wrote: Let's say I am online and I see an article on a web page. I copy and...