How to Buy a Computer for Creative Work

Build the best system for your needs without breaking the bank.

This article appears in Issue 40 of CreativePro Magazine.

So, you’ve started to think about buying a new computer, but got lost navigating the latest hardware options? You’re not alone. Today’s choices can be more challenging than in the past. Will more CPU cores or more memory make a difference? What about the GPU, and do you need an NPU? How do you weigh options on a budget?

The answers depend on one more question: What kind of creative work do you do? Understanding the needs of your creative discipline, whether it’s graphic design, photo editing, video creation, or 3D, will help you determine how to configure your next computer. Likewise, a quick review of some basic hardware concepts will help decode those specs lists you’ve been comparing. Let’s start at the beginning.

Computers Get Complicated

When computers first became widely used as creative tools, choosing one was relatively simple. You wanted a fast central processing unit (CPU), enough random access memory (RAM, which is memory used to do the work), and enough storage for applications and files. Now, GPUs, NPUs, and more components complicate the buying decision, and seeing that alphabet soup of TLAs (three-letter acronyms) on a computer spec sheet makes your eyes glaze over. Don’t worry, I’ve included a glossary of important TLAs at the end of this article.

To understand how we got to this point, let’s review some history.

Specialized processors emerge

In early computers, the CPU did everything, from basic calculations to processing graphics, photos, and video. This worked until advancing software demands hit a point of diminishing returns where the single processor would become too busy and hot to get things done any faster. Imagine a Design department of one person that’s given more and more tasks to accomplish. Something had

to change, so over time, the industry came up with a number of solutions that are now standard (Figure 1).

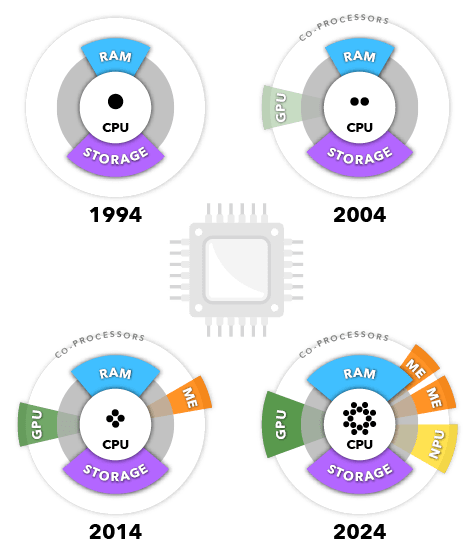

Figure 1. Over three decades, the CPU gained cores, and engineers added specialized co-processors such as the GPU, media engine (ME), and NPU, resulting in today’s high-performance computers.

In the 2000s one solution put multiple CPU chips in the computer, but few applications could take advantage of multiple processors at first. Eventually, the industry settled on making a single CPU with multiple cores in it (like a single Design department with multiple co-workers in it to share the tasks). The Windows and macOS operating systems came to support distributing tasks among those cores (called multi-core processing), and the number of cores in CPUs increased rapidly. Today, even budget computers have CPUs with eight cores, and pro-level computers can have many more.

Another solution took popular types of calculations away from the CPU and assigned them to specialized processors (sometimes called co-processors or accelerators) that can do a specific set of tasks a lot faster than the CPU can (think of this as hiring specialists to help the Design department). One example is graphics processing, which became delegated to a graphics processing unit (GPU). For the last 20 years or so, computers have come with either integrated graphics (on the same chip as the CPU) or discrete graphics (a component separate from the CPU).

When high-definition video became widely popular, another solution was needed. HD video needs a lot of compression to keep file sizes and data rates manageable on a computer, but compressing and decompressing video added too much to the burden on a CPU already busy enough with processing video frames. To make high-resolution video practical, computers started including a specialized processor, sometimes called a video accelerator or media engine, optimized for common video compression/decompression (codec) routines. A media engine can process video much faster than a CPU while using less energy, making it practical for a laptop or phone to play video smoothly for many hours on battery. If the CPU had to do that work, a video would play less smoothly, the battery would drain much faster, and the device would run much hotter.

Computers and mobile devices now include all of these components: a multicore CPU, a GPU, and a media engine. The CPU does general processing, the GPU accelerates graphics processing, and the media engine does low-power acceleration of video and audio processing. All of those can be important for design, photo, and video apps, although as you’ll see, various creative disciplines don’t all need them equally.

Future-ready processors

Newer computers advertise something called a neural processing engine (NPU), which accelerates machine learning and AI tasks. (Apple calls their NPU the Apple Neural Engine.) However, most Windows and macOS apps, including most Creative Cloud apps, do not take full advantage of an NPU at this time. For now, the other co-processors are much more important.

There’s More than One Kind of Memory

You might see computer specs abbreviated in a form such as “16 GB/512 GB” which is two amounts of memory. Why two amounts? Because they’re different kinds of memory.

The first, smaller amount is usually RAM, or the working memory the computer uses to think and process. The second, much larger amount is for storage, the memory used for keeping applications and files.

An easy way to understand these two kinds of memory is to use the analogy of a traditional art studio: RAM is like the size of a work table, and storage is like the capacity of file cabinets and shelves. The bigger your work table (RAM), the more you can keep work materials immediately at hand and have the space to work on larger projects. The more capacity you have in your file cabinets and shelves (storage), the more of your work and materials you can keep for retrieval in the same room.

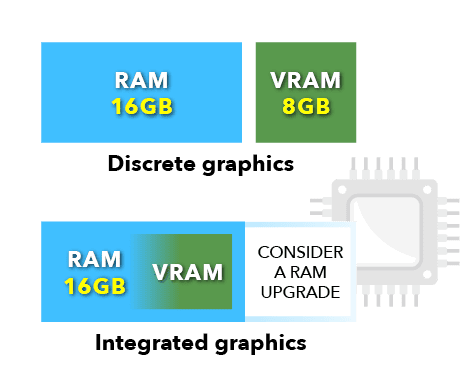

The latest computers use memory in other important ways (Figure 2). The GPU needs memory to do its processing, sometimes called graphics memory or video RAM (VRAM). In computers with discrete graphics, the GPU has its own memory. In computers with integrated graphics, the RAM that the operating system and applications use is also used by the GPU. Either way, if you use applications that rely heavily on the GPU, you’ll want to make sure it has enough of its own memory. For example, suppose your favorite application recommends 16 GB of RAM and 8 GB of graphics memory. If the computer has discrete graphics, you might order it with 16 GB RAM and a GPU with 8 GB of its own VRAM. If the computer has integrated graphics, you might order it with at least 24 GB of RAM so that the total is enough for the system, applications, and graphics to share. (However, the next step up from 16 GB is usually 32 GB.) For Macs with Apple Silicon chips, Apple calls RAM Unified Memory to indicate that the system, applications, and graphics dynamically share the same pool of memory.

Figure 2. With discrete graphics, the OS and the GPU have their own RAM. With integrated graphics, the OS and GPU share the same RAM, so consider adding RAM.

Other ways your computer uses storage memory

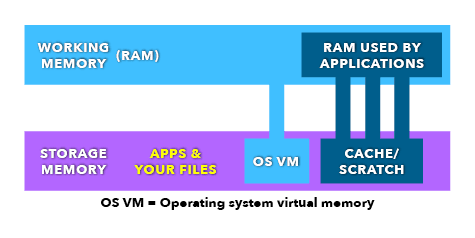

If the computer is so busy that free RAM gets low, storage can be asked to help (Figure 3). First, the system might start compressing some of the data in RAM. If memory demands keep increasing, the system will start using storage as working memory. Storage used this way is sometimes called virtual memory (VM) or swap because the system swaps data between RAM and invisible temporary files on your storage.

Figure 3. We think of storage as where apps and files are stored, but free storage space is also important for accommodating large temporary files created by the OS and apps.

Similarly, many creative applications, especially photo and video editors, also make heavy use of their own large temporary files. They’re typically performance caches, employed to keep things fast as you work. Some caches can grow to many gigabytes.

If you order a computer with too little RAM and too little storage (such as a base model), it’s more likely that the computer might slow down. If the computer runs low on RAM and there isn’t enough free storage space to help as virtual memory or to hold large temporary files, the computer is out of options and could become unstable. When you order internal storage, the amount should be large enough that after installing all your apps and files, there’s still at least a couple hundred gigabytes of unused space so that these temporary files have room to grow and shrink as needed.

How to think about storage

If you look at your current internal storage and it’s close to full, you probably need the next largest size for your new system. For example, if your computer has 512 GB of storage on the startup volume and there’s only 50 GB free, replacing that with the next size up (typically 1 TB) will help ensure that there’s plenty of room for large temporary files.

Is external storage an option? Yes, especially for project files. The more project files you can store on external volumes, the less you need to increase internal storage. Additionally, the applications you use might be able to relocate temporary cache files to an external volume. For example, Photoshop lets you assign the temporary space it needs to an external volume (scratch disk), and Adobe video apps let you locate their Media Cache files on an external volume. A volume that you use for temporary files needs to be a fast SSD (solid state drive) and have hundreds of gigabytes of free space; don’t use an old, slow, mechanical hard drive for this.

What About Displays?

Display quality, including color accuracy, has greatly increased in recent years. For example, an Apple M4 MacBook Pro comes with an accurate wide color gamut display that meets Adobe luminance requirements for HDR (high dynamic range) editing in Adobe Camera Raw, Photoshop, and Lightroom.

But you might not need all of that. If your work is primarily for web/mobile design or print, you might not need all of those capabilities. However, if your clients do require wide color gamut or HDR, then make sure to buy a display that supports them.

I’ll go into more detail about displays in a future CreativePro article.

Configuring a Computer to Support Your Work

After you have a basic understanding of computer components, you can work out an appropriate mix for the creative work you do.

Keep in mind that this section provides general guidelines; always look up the system requirements for the actual applications you use. When you see system requirements divided into “Minimum” and “Recommended” levels, budget for the Recommended level because the Minimum level might not be designed for deadline-oriented production workloads.

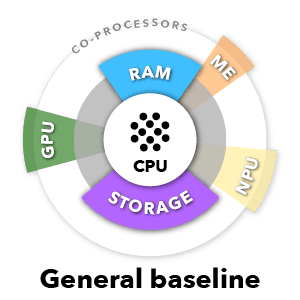

Here’s a rough baseline configuration (Figure 4) that can work well for general creative workloads:

- CPU: 10–16 cores.

- RAM (Unified Memory for Macs): 24–32 GB. If the GPU is integrated, add another 8 GB.

- GPU: For PCs, a recent discrete graphics card with 8 GB of graphics memory. For Macs, 16–20 GPU cores.

- Internal storage: Depends on the applications you run. Choose an amount that leaves several hundred gigabytes of space available for large temporary files.

- Media engine: One.

- NPU: Whatever the computer has is fine, because the NPU is not widely used at this time.

Those specs are considered midrange for computers being sold at the time this article was published. Now let’s adjust those specs for specific creative media.

Figure 4. For a general baseline configuration, focus on RAM, CPU, storage, and GPU.

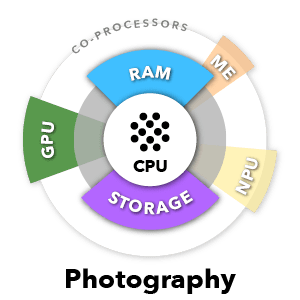

Photography

The baseline configuration above should work well if your photo edits and the image dimensions in pixels are modest, such as for web display or small print sizes. Consider upgrading the CPU, GPU, RAM, and storage beyond the baseline (Figure 5) if you frequently:

- Edit images with a large number of pixels, such as from a 36-megapixel camera. That’s roughly equal to 24 by 16 inches at 300 pixels per inch.

- Edit large shoots or batches at once, for example by syncing edits across hundreds of images using software such as Adobe Lightroom Classic or Adobe Camera Raw.

- Use machine learning and AI features, which tend to be GPU-accelerated. In Lightroom and Camera Raw, the speed of the popular AI-powered Denoise feature is specifically tied to GPU performance; adding more CPU cores or RAM doesn’t help.

Figure 5. For photography, the GPU and RAM become more important, especially for AI features. Batch processing might benefit from more CPU cores, depending on the software.

2D graphic design

The baseline configuration in Figure 4 should work well for general graphic design and layout for print, web, and online graphic design and illustration. Design applications such as Adobe Illustrator and Adobe InDesign usually won’t come close to maxing out all CPU cores and GPU power in high-end configurations, so adding CPU cores and GPU power doesn’t always help. (You do need a good GPU; you just don’t need the most expensive one.) What usually makes current design applications faster is higher single-core CPU performance, which typically comes with the next generation of processors (such as the single-core performance improvement of the Apple M4 over the M3 and earlier).

As 2D design applications add more features that use machine learning and AI, GPU performance will become more important. At Adobe MAX 2024, Adobe stated that they wanted Illustrator to take better advantage of multiple CPU cores and GPU acceleration, but they weren’t specific about how quickly or which areas would benefit first.

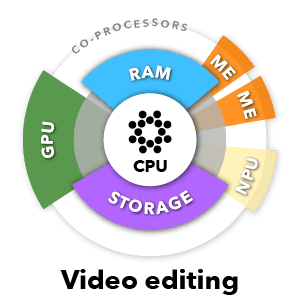

Video editing and visual effects

Editing video is much more demanding than photography or graphic design for one simple reason: Instead of updating a single static image, the computer might have to reprocess hundreds or even thousands of video frames every time you make a change or export.

The baseline configuration might work for moderate levels of video editing and visual effects. But if you do this kind of work daily, you’ll be happier with upgrades to CPU, GPU, RAM, and storage beyond the baseline (Figure 6) if you frequently:

- Edit larger frame sizes, such as 4K and higher

- Add many video tracks, because you edit productions involving many cameras or layers of video, graphics, type, and animations

- Apply many video and audio effects

- Apply AI-powered features

- Edit long-form video projects

Figure 6. Video editing and visual effects require higher performance from the CPU and GPU, and at least one media engine (ME) to accelerate video processing.

Pay attention to which features of your multimedia applications are GPU-accelerated, because the more of those you use, the more it will help to upgrade the GPU.

After Effects benefits from a RAM upgrade, in part because more RAM extends the time it can play a real-time preview of a composition.

For these applications it’s especially important to have hundreds of gigabytes of free storage space for their large temporary files, such as the Media Cache that Adobe video applications use to enhance performance.

A media engine coprocessor (video accelerator) becomes important with these applications, helping the computer play back video smoothly as you edit, accelerating previews, and exporting. The more important that is to you, the more you might upgrade to a computer with a more powerful media engine or more of them. For example, the Max and Ultra levels of Apple Silicon processors have two video encoding/decoding engines, while the base and Pro levels have one.

The NPU is not a major factor… yet. But some features in Apple Final Cut Pro and Apple Motion use the Apple Neural Engine NPU. At Adobe MAX 2024, Adobe announced that Premiere Pro for Windows will be its first application to use the NPU on Copilot+ PCs.

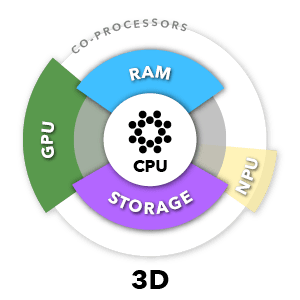

3D

3D can strain a computer as much as video editing. A 3D document can require calculating the positions, volumes, and interactions of hundreds or thousands of vector objects, and the materials and textures applied to them, with lighting, in three dimensions.

For complex 3D models or scenes, the additional demands on CPU, GPU, and RAM can be a bit much for our midrange baseline configuration to handle. A 3D application can benefit from upgrading to more CPU cores, additional RAM, and especially a more powerful GPU (Figure 7). A high-end GPU that supports ray tracing can speed final rendering and lighting of a 3D scene. Some 3D apps are starting to use the NPU.

Figure 7. The demands of 3D can be similar to video editing, except that the video-focused media engine is not as important.

The most demanding application wins

If you frequently work in more than one of the above disciplines, your most demanding application dictates how you configure your computer. For example, if you do page layout as well as editing the vector graphics and photos that go into your layouts, you’ll configure a computer based on the requirements of photography because that’s the most demanding of your jobs.

Power Efficiency Pays Dividends

If your current computer gets hot with noisy fans, you might want to pay attention to power efficiency in your next computer. If you’re comparing two computers and one uses less energy (fewer watts) to reach the same level of performance, you’ll typically benefit from that energy efficiency in multiple ways:

- Sustained high performance. Lower power use means less heat generated. The less time a computer spends at its maximum temperature, the more time it can perform at its maximum speed.

- Noise. The cooler a computer runs, the less it has to increase cooling fan speed to a noisy level.

- Battery life for laptops. The less energy a laptop needs to achieve a certain performance level, the longer you can use it without having to plug in the power cable. And the less often a battery drains to empty, the longer it can retain its full capacity.

Should You Max It Out?

In the past, it was common to recommend “maxing out” the options for a new computer for creative work. That’s no longer generally true as computers have gotten much more capable for the price. You might notice that the baseline configuration falls well below the maximum specifications for many PCs and Macs, except possibly the models at the low end.

For example, if you max out an M4 MacBook Pro (excluding storage upgrades), you could spend around $5200. But if you mostly work with Photoshop and InDesign, a fair amount of the maxed-out configuration’s 128 GB of Unified Memory, two media engines, 16 CPU cores, and 40 GPU cores that you paid for will not be used most of the time.

You’ll save money by being mindful of which parts of a computer your creative applications actually use the most.

What’s Next: Keep an Eye on AI

In recent years, GPU requirements for creative apps have risen more quickly than in the past. For a while, this was because software companies were finding more ways to take advantage of GPU acceleration. More recently, features such as AI masking and generative AI have been a major driver in increasing GPU requirements in recent versions of Photoshop, Camera Raw, and Lightroom Classic. Although the NPU is not yet widely used, if apps start to depend on it to accelerate AI features, that will further widen the AI performance gap with older computers lacking an NPU.

The effort to make AI features mainstream is changing system requirements at a basic level. Microsoft recently published the Copilot+ PC standard, which establishes a baseline for memory, GPU, and NPU that is built around supporting future AI features. Apple recently decided to raise the base amount of Unified Memory (RAM) in Macs from 8 GB to 16 GB; it’s thought that this was to help the recently released Apple Intelligence AI features run smoothly.

Even if you don’t use AI features, they are already influencing how quickly hardware requirements will soon change. So, as you research a better computer for what you do now, keep one eye on what you may do in the future, too.

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

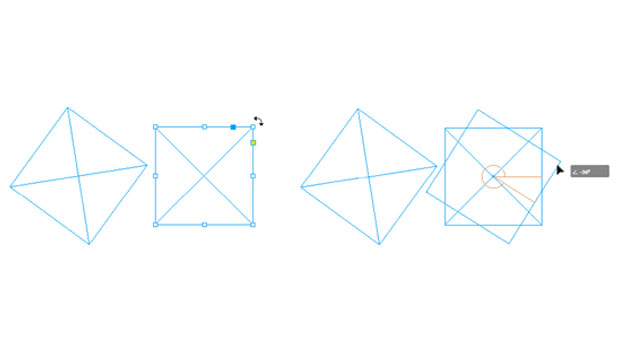

InQuestion: Applying Consistent Rotations With Smart Guides

Maya P. Lim explores the environmental impact of print design work and sustainab...

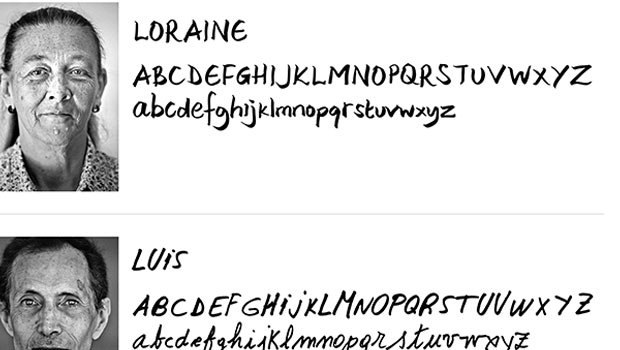

Fonts to Help the Homeless

Good things often spring from the union of commerce, art, and charity, as these...

CreativePro Week 2026 Agenda Announced

This year’s agenda includes 70+ expert-led sessions focused on the workflows, te...