Heavy Metal Madness: Keyboards I Have Known and Loved

Keyboard Hall of Fame

I can’t comment yet on what it’s like to type on a 1926 Intertype keyboard, though I’ll let you know sometime soon. But I have had the pleasure and horror of working on quite a few different keyboards in my time, and I do not underestimate the role they play in creativity and efficiency.

It’s not that modern keyboards are so bad — manufacturing improvements have made them pretty functional, ergonomics have improved some, and now at least the colors match your computer (which seems to be more important to most buyers than long-term comfort).

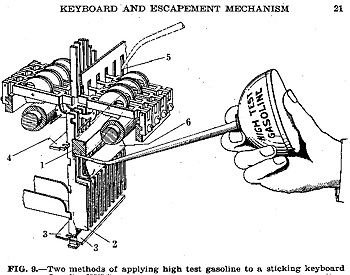

But for a mechanical-thinking person like myself, the comparison between an Apple Pro Keyboard, and one from any variety of ’70s-based composing systems, is like Rock vs. Jazz — they both have merits, but one is a pleasure to use and the other one drives me nuts. For one thing, you can give up trying to repair a modern computer keyboard. No amount of WD-40 seems to fix them these days, and you can’t even get most of them apart. You certainly can’t free their sticky mechanism by using high-test gasoline, which is recommended in one of my Intertype instruction books (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Long before OSHA cleaned up the workplace, high-test gasoline was a useful tool for freeing up sticky keyboard mechanisms. Don’t try this on your Mac keyboard, though I’ve heard it works great for Windows machines.

My favorite keyboard was the ULTRAcount 2000 from AKI (Automix Keyboards, Inc.) in Redmond, Washington. AKI made all sorts of terrific keyboards which were favored by typesetters for their pure speed — you could really fly through copy on an AKI, and they had lots of specialized keys. (What good is a keyboard “shortcut” if it involves depressing two keys and has to be either memorized or looked up?) Keyboards like the ULTRAcount had lots of keypads — you were never more than a single-click away from any command. Plus, my wife dubbed this one the “Star Trek Keyboard” because of its similarity to something you’d find on the bridge. We could imagine Sulu spinning its first-ever trackball (which was actually a white cue ball adapted for the job) or thrashing back and forth in his chair while piloting through a rough set of copy (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: More power, Scotty — we’ve got a long book to set here. The AKI ULTRAcount 2000 was the first keyboard to include a trackball for easy editing and was painted a very pleasant blue.

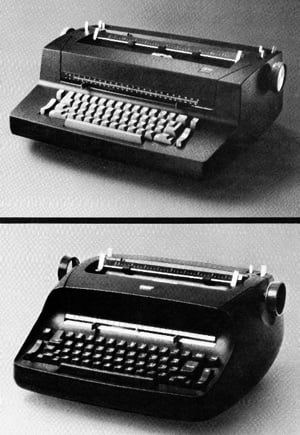

Most serious writers pine after the keyboard on the IBM Selectric or Selectric II typewriters (see Figure 10). Those machines are still a pleasure to type on, and they came in such wild colors. But in my evaluation, it wasn’t so much the keyboard that made the difference (it was one of the first to use pitch-topped keys), it was the way that type ball spun and whacked the page as you composed. Selectrics were good heavy machines that felt solid and assured, and for an entire generation of writers they got out of the way and let them fly through copy and reliably pound it on to the page.

Figure 10: The IBM Selectric Typewriter was released in 1961. Designed by Eliot Noyes, the first model and its successors (II and III) went on to capture over 75 percent of the typewriter market. Many best-selling authors still use Selectric typewriters.

My worst keyboard was definitely the AlphaComp II from Alphatype. Despite the promotional photos showing speeding hands busily producing profits (see figure 11), it was a horrible machine that caused me to swear violently and curse the day I’d bought it. But that was from a combination of flaws, frankly, and proves that even the best keyboard can’t save some machines from the junk heap.

Figure 11: The Keyboard Hall of Shame: The AlphaComp II caused hands to fly, as pictured here in a sales brochure, but frustrated even the most conservative typesetter to the point of cursing and throwing things.

The Key is Not the Key, but the Keyer is the Key

While I wish someone would after-market high-end keyboards designed for use with specific applications, the thing I miss most about the era of good keyboards is not so much the physical gear, but the spirit of camaraderie and creativity that came from having to retype so much stuff. When I was working on my college newspaper, it was composed at a large print shop in Los Angeles. The operator of the display-type machine — a Compugraphic 7200 Headliner — was an old guy named Pat with ears large enough to cause a stir among new staffers. When Pat delivered our headlines for proofing, he’d always say the same thing: “I set them the way you asked, but threw in a few alternates that might fit a little better.” And every time, we’d pick one of his headlines to run in the paper.

Re-typing copy was part of the editing process in a good shop, so when that was eliminated by networks and memory devices, we lost an important quality-control step. And when you knew from the start that making changes was a big deal, causing someone to have to go back to a machine and type it all over again, you were more careful in the writing and copy-editing stages. We’ve lost that, too.

I’ll let you know soon what it feels like to type on a machine as big as the Intertype with it’s rusted-metal keys and odd layout. And I’m desperately hoping that one of the new features in a future QuarkXPress is a “Big-Eared Pat” pop-up dialog box that gives me witty alternate suggestions to my own and others’ writing.

Read more by Gene Gable.

This article was last modified on March 2, 2021

This article was first published on March 20, 2003

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Tip of the Week: Controlling the Order of Scripts in the Scripts Panel

This InDesign tip on How to control the order of scripts in the Scripts panel wa...

Zevrix Solutions Releases InPreflight 2 Public Beta for Adobe InDesign

Zevrix Solutions today announced the release of public beta of InPreflight 2, a...

CreativePro Week Conference Speaker Spotlight: Laura Brady, Ebook Converter Extraordinaire

Fun facts about some of our favorite people, the speakers at our upcoming PePcon...