Heavy Metal Madness: A Woman's Work is Never Done

A few months ago at a rare family get together, when it came time for clearing the table and cleaning the dishes, my Swiss brother-in-law made some sort of reference to it being “women’s work.” As a well-intentioned liberal, I hate to generalize, but since my sister moved to Switzerland, I’ve learned a couple of things about the Swiss (women only received the right to vote there in 1971) that made this statement not surprising to me, and it was delivered in the matter-of-fact tone that seems to accompany every such statement I’ve heard from my brother-in-law and his family.

Housework is defined by most studies as cooking, cleaning, grocery shopping, laundry, washing dishes, doing repairs, paying bills, making arrangements, and caring for children. And all with a big smile!

I can’t reprint here the words that came out of my wife Patty’s mouth in response to this “statement of fact” from my brother-in-law, or the next time you visited creativepro.com you’d have to check a box certifying that you are over the age of 18. But for some reason, my sister willingly chooses to take on this “women’s work,” and she does it in a dress and full makeup. Sadly, in researching the imagery of women and housework for this column, I’ve discovered that she is not alone.

Cooking a big roast while wearing a dress was routine in the fifties and sixties as shown in this photo from the terrific book “Populuxe” by Thomas Hind. Now the only woman I know who still behaves this way is my sister, but then she’s married to a Swiss guy and they seem to have pretty high standards for “women’s work.”

Many of you will look at the images in this column and not be terribly surprised — they appear to be a glimpse at a by-gone era, a time that seems laughable now, like when dresses touched the floor and hairdos reached for the sky. And it’s true that the fashion and tools of housework have changed considerably, and may have even created the illusion of equality. But the truth is, women still carry the bulk of the load when it comes to cleaning, laundry, and the other drudgeries of daily life.

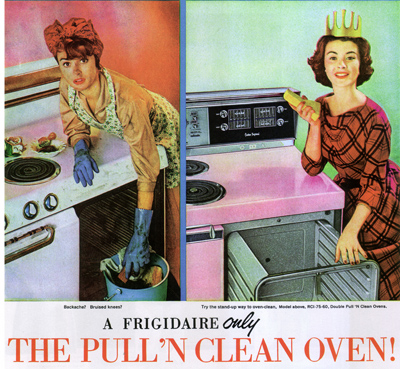

In 1966 as shown in this Frigidaire ad, women were still slaving over dirty stoves while secretly wanting to feel like a Queen. And yes, you really could get pink and baby-blue models. This was the year that General Electric first introduced avocado appliances, after all.

The Rid-Jid Ironing Table from the J. R. Clark Company boasted being the first such device with enough knee room so that the discriminating ironer could be seated during for the task at hand. This model arrived in sunshine yellow baked enamel and chrome.

The challenge for household-product marketers in today’s climate is to continue to target the female buyers of their soaps and other cleaning products without resorting to insulting stereotypes (though I continue to see plenty of those, too). Housework is still portrayed in its extremes — drudgery to be avoided and streamlined, or satisfying work that produces results to be proud of. Cleanliness has always been a big measure of status in our world, and much of the advertising for housekeeping products still plays in to our collective desire to present a life image that is tidy and under control.

Even back in 1951, one of the marketing angles used most to sell cleaning products was the good feeling that comes from disinfecting surfaces. According to the Soap and Detergent Association’s annual National Cleaning Survey, this is still the case: two out of every three Americans have recently used a disinfectant wipe, making those products one of the fastest growing segments of the housekeeping market.

Lincoln Metal Products made it possible for the discerning and well-dressed woman to avoid actually touching the garbage can with its line of “BeautyWare Kitchen Essentials.” Produced in gleaming chrome, a house maker could have matching garbage cans, canister sets, wastebaskets and breadbox. Date unknown.

Equal Is as Equal Does

According to various studies I uncovered, the split of housework between men and women has changed little over the last several decades, despite more women working full-time outside the home. Women do approximately 70 percent of housework, and men 30 percent. This split does not change significantly, either, when the woman also holds down a full-time job. And since the total housework increases for a married couple, women in those situations actually do considerably more housework — 14 hours more per week than a single woman. Married men, on the other hand, do only 90 minutes more work per week than their single counterparts (which many would argue is 90-minutes more than none).

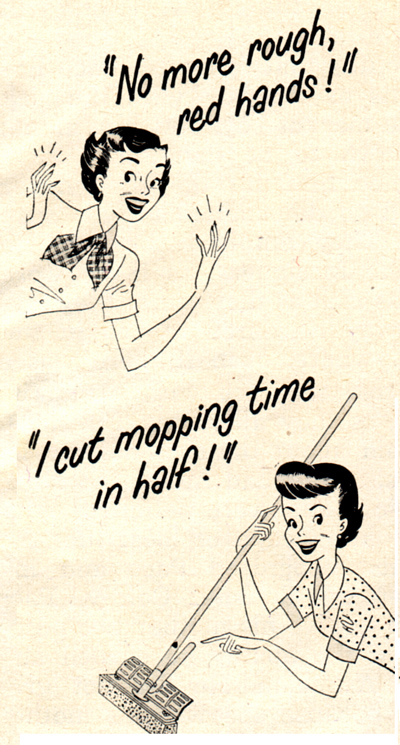

Women have always had energetic and embraceable sides, as highlighted in this 1951 ad for Trushay hand lotion. Only now instead of being split only in half, most women also carry a full or part-time job outside of the home.

We could debate for days the reasons why these figures have not changed significantly from when our mothers scrubbed the floors and folded the laundry, but we’d probably never reach any conclusions. Are men simply lazy, or do they have significantly lower standards for cleanliness? Do men over-estimate the contributions they make through their own jobs, thus feeling that they are somehow equal in their total contribution to the household? I’m sure both of these, and many other statements, are true.

What motivates women to continue their dominant role in housekeeping chores? The data shows a high level of personal goal-setting relative to cleanliness, and more recent studies also indicate that the tidiness of the house can become a direct measure of worth to some people.

I also found a study published in the Journal of Marriage and Family in 1999 that suggests women actually create the very inequality in housework that they say they resent. This is done through a process referred to as “Maternal Gatekeeping,” wherein women create obstacles for their partner’s contribution to housework by setting unachievable standards, or by doing work over again rather than accepting the contribution as is. There is also, according to the study at the heart of these conclusions, a need for validation that comes from housework that many women are unwilling to give up.

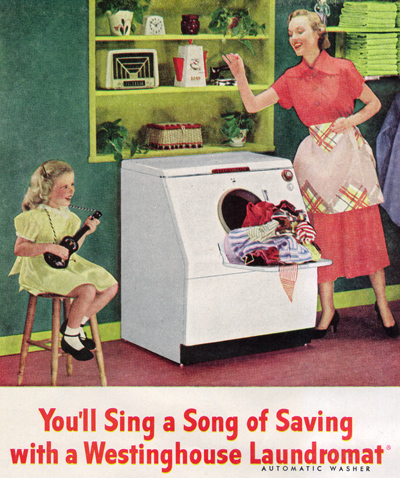

Learning from Mom, the way all good girls and boys do. The majority of Americans surveyed claimed to have learned cleaning routines and practices directly from their mother.

Fels-Naptha soap, once a staple of every woman’s cleaning closet claimed you could tell it was authentic “even with your eyes closed,” because of the “sweet, clean” aroma. Here, a mother and daughter enjoy a moment of guilty pleasure sniffing the washing machine while dad watches the big game.

But most research states the obvious: our mothers screwed us up in the area of housework just like they did in every other area of life. According to the Soap and Detergent Association of America, the majority of people surveyed say they clean in much the same manner as their mothers, though 17 percent admit to cleaning less than their mothers did, and we are typically using different products than good-old mom. So I guess we’ve made some progress. And you certainly don’t see as many aprons being worn these days.

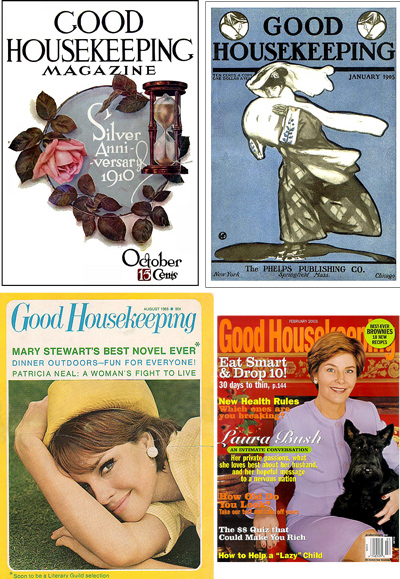

If you have any doubts as to the fact that women’s roles in house chores has not changed, just look at the 435,000 circulation of Good Housekeeping as a clue. The Hearst Corporation, publishers of GH, claim 1 out of 5 American women read Good Housekeeping each month looking for the latest tips and tricks.

I wouldn’t say my own mother was a clean freak, though she was (and still is) a germ freak. To this day my mother considers her primary household responsibility to kill every virus, bacteria, or germ that exists in nature. Her biggest weapon in this fight is scalding hot water, and I did inherit that trait from her.

Cleaning Habits and Personalities

We may not have come very far in changing the gender mix in housekeeping responsibilities, but we do understand cleaning behavior better, and that has helped marketers target better. According to the Soap and Detergent Association, there are five types of cleaning personalities:

“Clean Extremes” are the largest category (25 percent of women), and they agree with the statement that “it’s important that my home be clean even where people don’t see.” According to the SDA, these women can’t relax unless their home is spotless, and that a clean home provides an overall feeling of well being and personal satisfaction.

Visitor impressions have always been key angle in marketing cleaning or other household product. After all, your home is the one place where you can show off with pride.

“Mess Busters” come in second at 24 percent, and like the Clean Extremes they want every area of their home clean, though according to the SDA “they don’t fret about housecleaning; they just do it.”

“Strugglers” (21 percent) do not consider housework to be an important part of their day-to-day lives, and typically say it simply builds up faster than they can keep up with. Ironically, this group actually spends the most amount of time on housework, but derives much less satisfaction from it. Strugglers, not surprisingly then, are more likely to be married, and have the largest families of the five personality types.

A good bucket can really put a smile on the weary home maker, as shown in this catalog-sheet illustration from the Republic Molding Company which promised a complete revolution in un-breakable pails.

“Dirt Dodgers” clean only when they absolutely have to, and represent 18 percent of women surveyed. Dirt Dodgers find it difficult to keep their home neat and organized, and have a much-lower level of satisfaction with the cleanliness of their homes.

“Mop Passers” are the smallest segment of women housekeepers (11 percent). Don’t jump to the conclusion that these are the messy ones, though. This group still desires a clean house, but is more likely to get help — keeping house is just not the personal priority for this group that it is for the others. These women, according to the SDA, spend a mere 6 hours a week on housecleaning.

O-Cedar Sponge Mops are still hawked to women looking for that perfect product that will leave their floors gleaming yet be gentle on their hands.

All of the five personalities agree, according to the Soap and Detergent Association, that the biggest bummer with cleaning is “that the house just gets dirty again.” This, I think, is the key to why men don’t do more housework. Why clean it today when it’s just going to be dirty again tomorrow?

I’m not sure if Republican women make better house keepers, but I can say it was easy to find pictures of first-ladies Nancy Reagan (above) and Laura Bush endorsing their role as home makers. I could find no similar images for Rosalyn Carter or Hillary Clinton who I’m betting were perfectly content with hiring out as soon as they could justify the expense (Mop Passers).

Maybe the Swiss habit of stating the obvious and then turning it into an intractable doctrine is not so far off here.

Read more by Gene Gable.

This article was last modified on May 19, 2023

This article was first published on March 31, 2005

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Removing Hair in Photoshop

A few years ago I was asked by a British newspaper if I could take a dozen celeb...

CreativePro Video: Recover Photo Detail With Camera Raw

In this week’s CreativePro video, Mark Heaps shows us how to use Photoshop’s Cam...

PhotoSpin Expands Their Lifestyle Collection With New Images By Yuri Arcurs

PhotoSpin, www.photospin.com, a leading royalty free stock subscription company...