Getting Started with GREP

Peter Kahrel shows how to get started with GREP.

This article appears in Issue 59 of InDesign Magazine.

Most people use InDesign the way they cook dinner: they know the basics, they can intuitively throw together some ingredients, or they can follow a basic recipe. But it turns out that if you know a little bit about food science, the chemistry behind the process, you can achieve wonders and impress both yourself and everyone around you. Similarly, by learning a little bit about some geeky stuff, you can do wonders that others can only dream of. If you’re looking for a way to supercharge your InDesign skills, there are few things as good as learning a bit of GREP. Unfortunately, GREP looks scary, and so people think it is scary. Not so! Like so many things that are reputedly difficult, GREP can be readily understood and used successfully at basic levels. First, let’s define what it is and what it’s good for. GREP is a search tool that you can employ just like the search tools in applications such as MS Word and Notepad to find literal text like nonplussed or understand. But you can make GREP searches more interesting and more useful by adding certain codes to search for text patterns instead of literal text. With GREP’s codes, you can do things like “find all words that consist of capital letters,” “find all words that end in ful,” “apply No Break to the last word of all paragraphs,” and countless others. In this article I’ll show you how to formulate GREP search patterns that are much more powerful and useful than InDesign’s standard search-and-replace tools. I won’t go into every aspect of GREP, but you can find some fantastic resources at CreativePro.com/resources/grep to fill in the gaps in your understanding of the basics of GREP. And at the end of the article I’ll point you

to other resources with more advanced techniques.

Finding Alternate Spellings

As I mentioned earlier, GREP is good at finding patterns, so it’s perfect for finding different spellings of the same word. We find spelling differences in variants of the same language, such as British English and American English, but consistent spelling errors, too, are in fact cases of spelling “variation.”

Examples of spelling differences in British and American English are grey–gray, centre–center, and colour–color. Notice that these three examples show three different types of variation, each of which can be found with a different GREP search. We’ll deal with them one by one.

The bracket: “match any ONE of these”

The first one, grey–gray, we can find typing the following into the GREP Find What field: gr[ea]y You can read [ea] as “e or a.” A bracketed string matches just one character in the text, and you can place as many characters in a bracketed string as you like. For example, b[aeiou]t can be read as “b, followed by a vowel, followed by t,” and will find bat, bet, bit, bot, and but. It will NOT find bait.

The pipe: “this or that”

Because the second type of variation, centre–center, involves two characters, it’s not convenient to use the bracketed notation. Instead, we list alternatives like this: cent(re|er) Here, the alternatives are grouped in parentheses and separated by a pipe (|). Alternatives don’t have to be the same length. For example, thr(u|ough) matches thru and through, and (X|Christ)mas matches Xmas and Christmas. And the alternatives can consist of any character; they don’t have to be letters. Thus, who(se|’s) matches whose and who’s. And finally, you can list any number of alternatives, as in the following search term: (pro|de|pre)scribe which matches proscribe, describe, and prescribe. Apart from searching alternate spellings of the same word, you can use the pipe notation to find different words altogether. For example, perhaps|maybe finds both perhaps and maybe. Note that in this case it’s not necessary to add parentheses. In the earlier example of cent(re|er), the parentheses were needed to isolate the alternatives from the main part of the word, cent.

The question mark: “there or not”

For the third type of variation, colour–color, you use yet a different method. This variation is determined by the presence or absence of a letter, here u. In GREP-speak we indicate the possible presence of a character by adding a question mark after it: colou?r The question mark can apply to any character; it doesn’t have to be a letter. So it’?s matches its and it’s. The scope of ? is just one preceding character—in other words, only the character immediately to the left of the question mark is optional—so that the search colou?r matches both color and colour. To make more characters optional—say, a prefix or a suffix—you place them in parentheses. Thus, to find the words cop and copper, you use this search term: cop(per)?

Combinations

The three different methods to find alternate spelling can be combined. For example, to find setup, set-up, and set up, you could use the following search term: set[- ]?up which you can read as “set, possibly followed by a hyphen or a space, followed by up.” Alternatives can be made optional, too. For example, to find the word claim and its inflections, use this search pattern: claim(s|ed|ing)? which matches claim, claims, claimed, and claiming. By placing ? after (s|ed|ing), the whole list of alternatives is made optional. If you leave out ?, claim is not found—only the three inflected forms are.

GREP Is Case-Sensitive

You may have noticed that GREP searches are case-sensitive. For example, the search term color doesn’t match Color. GREP searches, then, are case-sensitive by default. This is not a limitation of InDesign’s version of GREP, by the way; it’s a standard feature of GREP. In fact, it’s not a limitation at all: it actually makes using case-sensitivity much more flexible, something which we’ll return to later. There are several ways to make GREP case-insensitive, but for the moment let’s look at just one: [Cc]olor As you see, this comes down to the “alternative spelling” approach we outlined earlier: in essence, we’re saying that Color and color are alternative spellings of the same word, which is equivalent to setting a case-insensitive option.

Finding Series of Characters

Earlier, we mentioned this search term: b[aeiou]t and that it can be read as “b, followed by a vowel, followed by t,” matching bat, bet, bit, bot, and but. The search term finds just these five words because [aeiou] matches just one character. But we can change that slightly by adding a plus symbol, which in GREP means “one or more.” All of a sudden the expression becomes much more interesting: b[aeiou]+t The simple addition of + makes the search term match series of vowels, so that in addition to the five three-letter words, it will now find bait, boat, beat, and beaut as well. The + operator is used frequently because it’s so useful in defining patterns. For example, consider finding words of two or more syllables. In English, two-syllable words are characterized by sequences of at least vowels–consonants–vowels (oboe, eerie, etc.). The following search term will find that type of word: [aeiouy]+[bcdfghjklmnpqrstvwxz]+?[aeiouy]+ The pattern reads “one or more vowels, followed by one or more consonants, followed by one or more vowels.” To include two-syllable words that start with a consonant, add the consonants as an optional class using the ? operator: ([bcdfghjklmnpqrstvwxz]+)??[aeiouy]+?[bcdfg jklmnpqrstvwxz]+?[aeiouy]+ Note that by placing the first [b...z]+ in parentheses, the ? operator applies to that whole string, not just to +. Finally, note that the + operator can be used on single character too: the search term e+ matches any sequence of one or more es, as in beer and wheeeee!.

Characters and Classes of Characters

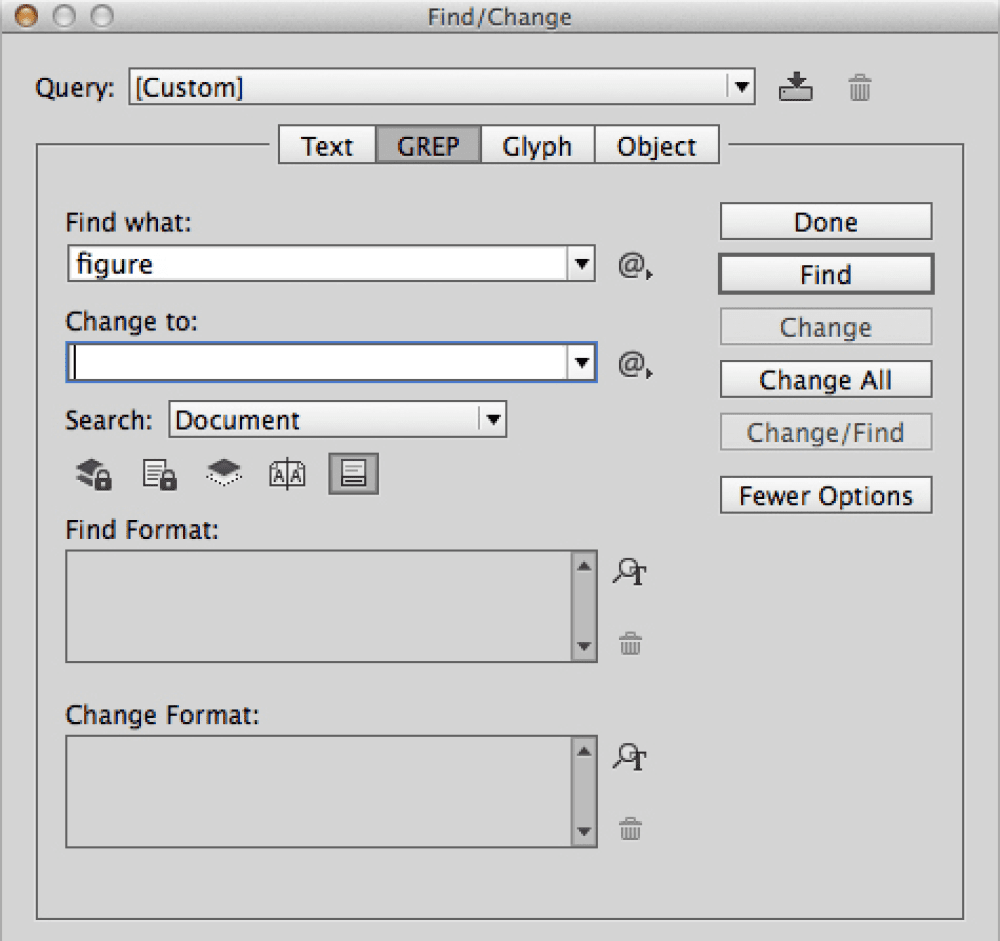

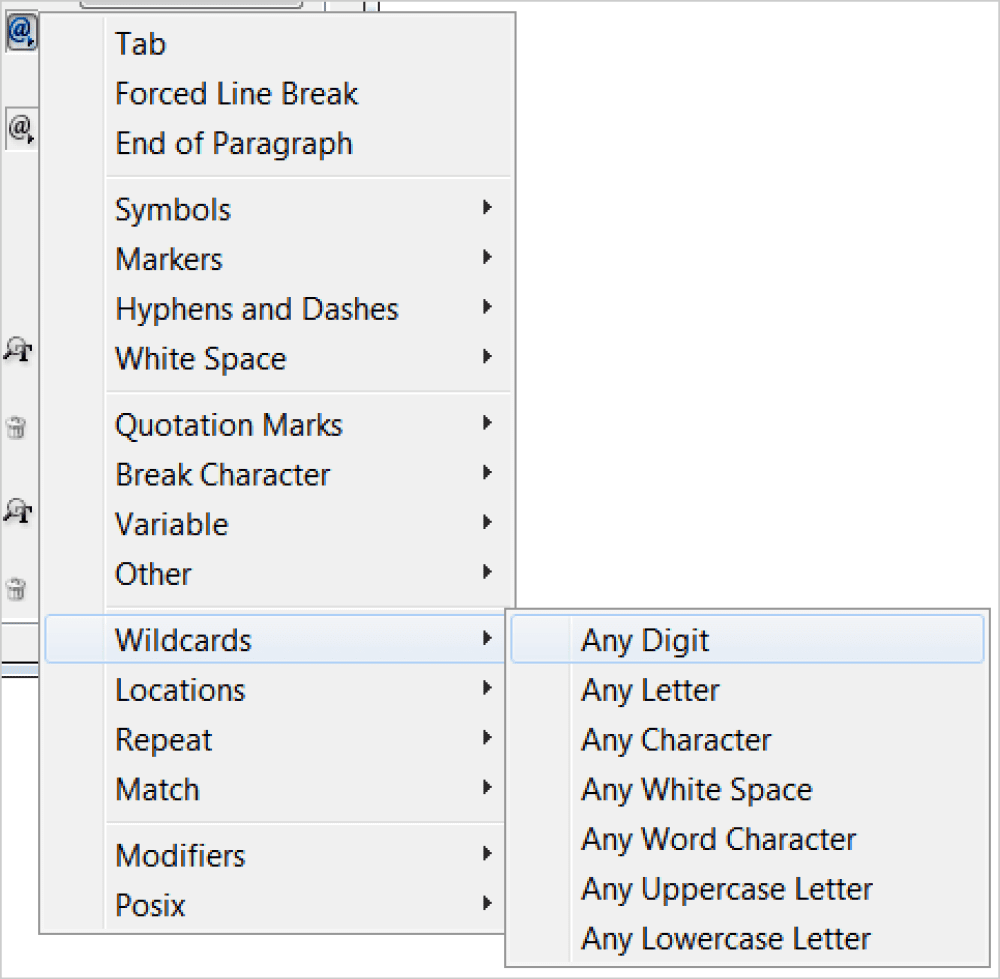

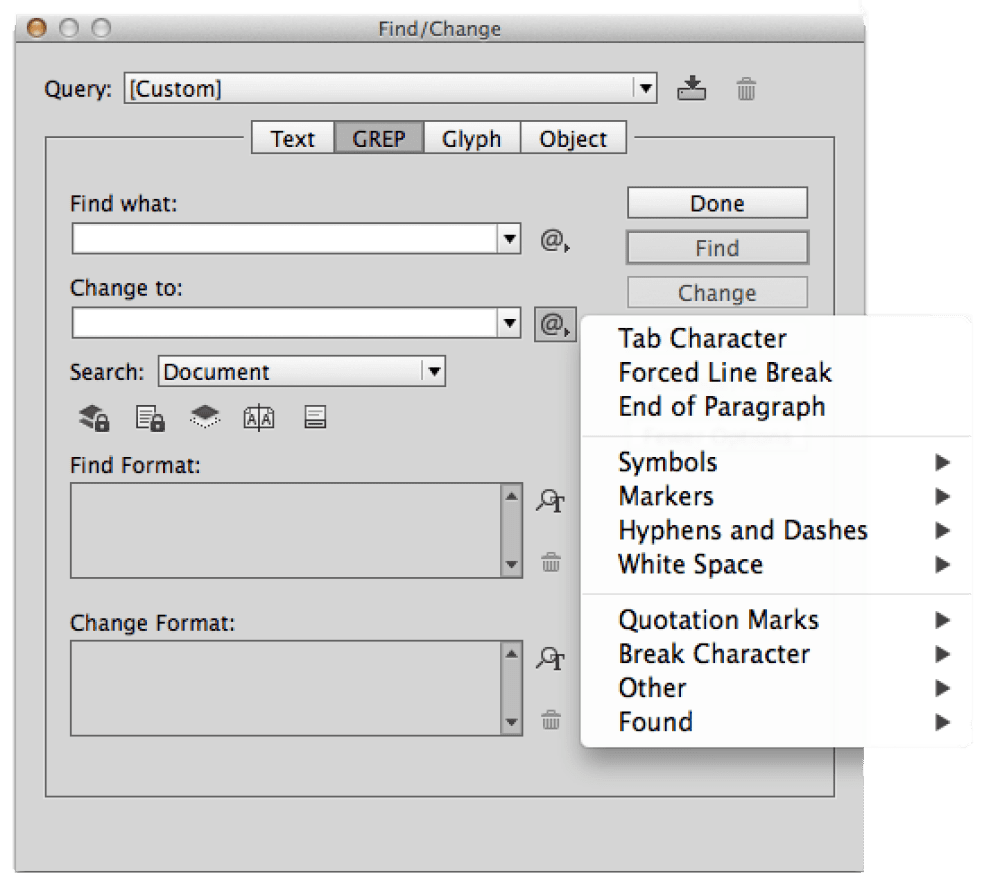

In the examples we saw earlier, we were looking for literal text such as center and copper. Even when we used some GREP codes to find word patterns—for example, searching for gr[ae]y to find both gray and grey—we were still looking for literal text; in other words, we were looking for characters. One step in the direction of a more general class of characters was an example we used above: [aeiouy], which you can read as “any vowel.” It’s easy to come up with other classes of characters: [bdfhklt] finds all ascender letters and [gjpqy] finds all descender letters. And you could come up with still more character classes, such as [ij], the class of letters that in English have a dot. All these are custom classes in the sense that you define them yourself for a particular purpose. However, apart from these custom classes, there are a number of standard GREP character classes. They are not defined in terms of “real” characters as we have been doing until now; instead, they use so-called wildcards (or you could call them “meta-characters”). The most popular GREP wildcards can be found in the Find/Change dialog box under the @ > Wildcards menu (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The wildcards menu

\d+ finds one or more digits, in other words, numbers, though only whole numbers. To find decimals as well, we have to create a class: [\d.]+. This search term finds (English) decimals such as 2.3 and 67.22. To find numbers with thousands separators too, simply add the comma: [\d.,]+. Now we can locate 1,234.56, as well as 3.456,12. See how flexible GREP classes are? We can combine literal characters and meta-characters in one class. And we can go even further if we want to find money amounts. All we need to do is add the currency symbols we’re interested in: [$£€¥\d.,]+

Letters

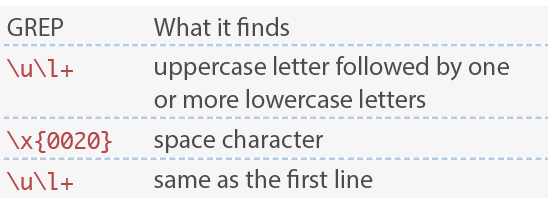

InDesign gives us three classes for letters: Any letter, Any Uppercase letter, and Any Lowercase Letter. They are straightforward: (that’s a lowercase L) matches lowercase letters, \u finds uppercase letters, and with Any letter, well, Adobe gave us a class that we could have done ourselves: [\u], which of course is the class of upper- and lowercase letters. With the two wildcards \u and we can do some sophisticated things, such as finding names. Let’s define a name for the moment as two consecutive words that start with an uppercase letter, such as Jane Hudson and James Morecambe. To find one word starting with a capital letter, we need the search term \u+: an uppercase letter followed by one or more lowercase letters. To find two such words, we simply use \u+\x{0020}\u+ (remember that we use \x{0020} for the space character because the space character is not always easy to spot in a search pattern). Search patterns like the one above can become a bit difficult to read, so we’ll use a different format whenever it seems appropriate, as follows (but when you write such search patterns in the Find What field of the Find/Change dialog box, you must leave out those comments and write the pattern as one line):  But of course names aren’t always as simple as this. For example, some people have double-barreled surnames such as Trevor-Roper. Such a name can be captured by saying that we’re after an uppercase letter followed by a class consisting of lowercase letters, uppercase letters, and a hyphen:

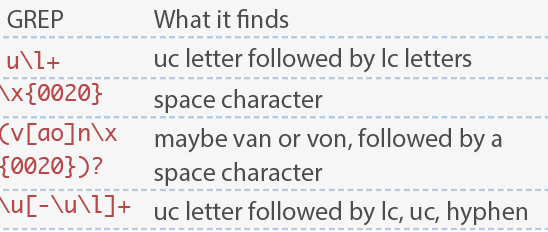

But of course names aren’t always as simple as this. For example, some people have double-barreled surnames such as Trevor-Roper. Such a name can be captured by saying that we’re after an uppercase letter followed by a class consisting of lowercase letters, uppercase letters, and a hyphen: \u[-\u]+. This pattern, by the way, also captures names with irregular capitalization such as LaGuardia. To locate prefixed names, like John von Neumann or Rip van Winkle, we have the following search patterns:  And because GREP is case-sensitive, the name prefix should in fact be written as

And because GREP is case-sensitive, the name prefix should in fact be written as ([Vv][oa]n\x{0020})?, so that we capture Van, van, Von, and von. As you see, matching names can be tricky, and the search pattern in its current state fails to capture various other possibilities, such as various prefixes de, du, le, van de, and von der, to mention just a few. With what you’ve learned so far, I’ll leave it up to you to formulate a pattern that matches all names.

Any white space

It’s convenient that we can use a single wildcard to find any kind of white space. matches all spaces (the normal space character, en- and em-dashes, thin spaces, half spaces, etc.), but also tabs and paragraph returns.

Any word character

This wildcard, \w, captures letters, digits, and the underscore character. I mention it here for completeness’ sake.

Any character

This wildcard, the dot ., punches well above its weight: this little fellow matches everything in a paragraph! Well, almost. It doesn’t match the paragraph mark (it could be made to, but we’ll not go into that here). If we add the + operator, we say in effect “one or more of everything (except the paragraph mark),” and that must be whole paragraphs. It’s easy to try out: type .+ in the Find What field, and click Find/Find Next a few times. You’ll see that each time you press Find Next, the next paragraph is highlighted.

Replacing Text

Replacing text using the GREP panel can be very straightforward, and just as simple as in any other application that offers a search-and-replace feature (Notepad, MS Word, etc.). Simply type a search term in the Find What field, a replacement text in the Change To field, and do the replacement. For example, to replace multiple paragraph marks with a single one, click in the Find What field, and then click the @ icon and choose End Of Paragraph from the menu. This inserts \r into the Find What field. Now type \r+, so that the Find what field reads \r\r+ (i.e., find two or more paragraph breaks). In the Change To field, type \r, and then press Change all. As in the Find What field, you can see a list of special characters by clicking the @ icon. Apart from the last item, all items are the same as in the special character list for the Find What field. However, it’s that last item, Found, that makes GREP replacements exciting (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Change to special characters

\u+ \x{0020} \u+ to find names like Jim Donegal. What we want to do is reverse the order of the first name and the surname and add a comma after the surname, so that we get Donegal, Jim. To achieve this, first we’ll add parentheses to the parts that we want to refer to later—the first name and the surname: (\u+)\x{0020}(\u+) That’s all. What is matched by the first line will be Found 1, and what’s matched by the third line will be Found 2. Now use the special characters list to insert Found 2, the surname, in the Change to field, which you’ll see appear as $2. Type a comma and a space, and then enter the reference to Found 1 by typing $1. The Change To field should contain the following line: $2, $1 Now, with GREP replacements you should always be very careful. Don’t rush into Change All straight away; first click Find, then Change. If the result looks good, click Find Next and Change. If it still looks good, use Change/Find or Change All. Like many specialized skills, using GREP can seem mysterious and daunting at first. But as the examples in this article show, almost anyone can understand and use GREP. All it takes is a little patience and practice, and you too can wield the amazing power of GREP in InDesign. Give it a try! You may soon wonder how you ever got along without it.

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

InDesign Magazine Issue 79: Tablet App Solutions

We’re happy to announce that InDesign Magazine Issue 79 (November, 2015) is...

GREP Find/Change on Formatted Text (solution to a big problem)

Daivd Blatner shows how InDesign's GREP Find/Change can mangle text formatting,...

GREP of the Month: Negating Characters

Learn how to exclude a single character (or a range of them) with these handy GR...