Scanning Around With Gene: The Photographic Moment of Truth

For several years in high school I worked part time at a small pharmacy that sold one of everything and had roots back to the soda-fountain days. Often on Saturdays, when I was the only employee other than the pharmacist, boredom would set in and I’d fill some of the time snooping on the customer photo-processing envelopes that had yet to be picked up.

Mostly this only contributed to the boredom and confirmed to me that when you point a camera at people or scenery, the results are pretty predictable. But watching people’s faces as they ripped open the processing envelopes was always entertaining. Sometimes they acted like it wasn’t important and would wait until they got in the car to look, and other times they would carefully go through each picture right there at the counter and give a running narrative of the subjects, even if no one was paying attention.

Getting your film-based prints back from the processing lab was a moment-of-truth ritual I’m glad to see go by the wayside, though I do miss some elements. Mostly the results were disappointing, whether from bad framing, poor exposure, a chemical or light disaster, or conflicted memories of those moments. With digital pictures we get instant gratification and the images we see on the little LCD screen immediately become the memory, regardless of how much they too might distort the truth.

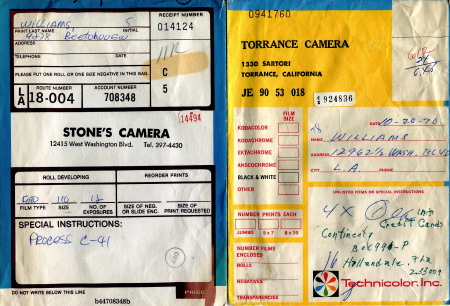

Entrusting your photos to someone for processing was usually a pretty casual choice, but for those of us who took our pictures seriously, it was a critical one. The convenience of the drive-through Fotomats and the color-coordinated “Fotomates” who inhabited those blue-and-yellow huts was tempting, but dangerous — color quality and reliability often suffered. The local camera store tended to use a high-quality lab, but prices were much higher. At drug-store chains like Thrifty or Sav-On, it was impossible to know where your film was going, let alone whether it would ever come back.

Unless you lived in a big city and knew your way around the photo scene there, it was nearly impossible to take your film directly to the processing lab. We didn’t have in-house one-hour machinery in those days, so you always had to wait (at least overnight and usually a week or more) to get your prints back.

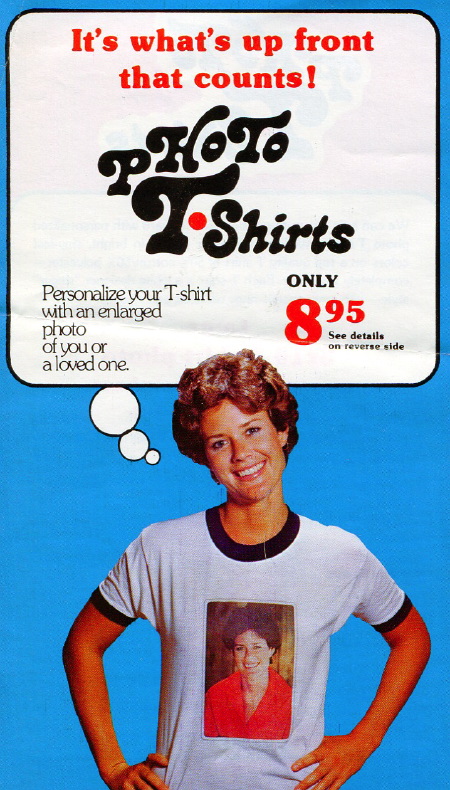

Many labs had a gimmick or at least a trademarked process they touted as better than the others. But mostly it came down to which one gave you the biggest or the most copies of your prints for the money. Double or even triple prints often meant double or triple the disappointment.

What was the dreaded “why your pictures look like crap” note? You won’t know unless you go to page 2.

This article was last modified on May 17, 2023

This article was first published on March 20, 2009