The Art of Business: Insider Tips for Working with Large Companies

One of my best clients is a very large technology company that shall remain nameless. This company is a leader in virtually every market in which it competes and regularly lands atop those prestigious lists of “Companies to Watch,” or “Best Companies To Work For,” or “Slam Dunk Investments,” and so forth.

I’m sure all of the accolades are deserved. But often, I’m amazed at how non-strategic, illogical, and shortsighted the company can be. I’ve worked for other large companies and they’re no different — some are even worse. These experiences have led me to postulate Adams’ Law of Corporate Inanity:

The sensibility of any organization is inversely proportional to its size.

Lunatic, But Lucrative

When you work with big companies, don’t let them drive you crazy, too. Instead, follow, these tips:

1. Be prepared to work quickly. You’d think that corporations, with all their resources and strategic thinkers, would have the wherewithal to plan projects in a timely fashion. But most corporations seem to work in a panic mode with ridiculously short deadlines and convoluted constraints. “Need it yesterday” is standard operating procedure, so be ready to make big sacrifices for those big contracts.

2. Be ready for a cold shoulder. The average corporate employee spends an inordinate amount of time in meetings and countless hours on foolish paperwork. They’re overworked and under appreciated; even more so in economic downturns because coworkers get laid off, and those left behind are asked to pick up the slack.

The remaining people often manage to keep afloat simply by ignoring unsolicited (and often solicited) emails and phone calls. So when a corporate employee fails to respond, don’t take it personally. Persevere and sooner or later they’ll return your calls, often starting with an apology for the delay.

3. Understand the underlying driving needs. In large companies, no one does anything “just because.” Every project is driven by something, someone, somewhere. Every project always seem to be part of some larger initiative handed down from on high with its own set of parameters and immutable rules that will invariably be enforced only after the project is complete and late in the review stage. To help save you time later, ask about the big picture before getting started on a project.

4. Be ready to justify yourself. Small-business people can make decisions on any criteria they choose. Corporate employees, on the other hand, must justify their expenditures to someone else in the organization, often many people. Additionally, employees often are afraid to champion an idea or vendor for fear of being shot down by a manager or executive above them. So one of your key jobs is to provide ample evidence of your value and worth so that your contact feels bold enough to risk suggesting that you and your solution are the best choice. Rather than provide justification anecdotally or in person, provide it in a format that is easily understood and can move up the chain of command. This means comprehensive PowerPoint or Web presentations or written proposals.

5. Understand the Holy Grail of ROI. Large companies, especially in lean times, love that thing called return on investment. You may not be a numbers person by nature, but your proposals will be stronger if you show how your solution will affect or enhance the company’s bottom line. Include real-life examples of results at other companies. Illustrations with charts and graphs are more convincing than any brochure. If you’re more expensive than your competition, what added value will you provide? If hiring you will cost more than solving the company’s problem in some other way, what tangible benefits will they receive that make the added expense worthwhile? Spreadsheets aren’t artistic, but they’re beautiful if they land you a big job.

6. Beware the budget axe. Even when a company needs you badly and you’re obviously the best one for the job, the deal won’t go through if there’s no money in the budget. The budget axe can come crashing down at any moment; there’s usually no warning and less recompense. You can ask your contact to try for a budget variance or offer delayed payment terms, but no budget usually means your project will be deferred until the next fiscal quarter or year.

That’s why it’s not a bad idea to ask your client early in the process if there’s a firm budget for the project in question. Don’t necessarily expect them to tell you how much it is — price negotiations will come later. But if your contact can’t answer budget questions, it’s also a strong clue there is no budget or, worse, you’re not talking to the decision-maker.

7. Understand chain of command. Your chance of landing a deal and remaining in good graces is in direct proportion to the number of actual decision-makers you sit in front of. Many creative professionals are content to speak with someone who must answer to someone else. Don’t leave it up to anyone to sell your case. Be bold and ask who the decision maker is, and then create a relationship with the decision maker.

If you’ve never worked in the corporate world, find a friend who has, and ask him or her about the ways things really are inside those monster buildings. You’ll be thankful for the relatively tame problems of being a creative professional.

This article was last modified on January 6, 2023

This article was first published on October 10, 2005

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Creative Blöks: Shinefools

Last time out, we encountered the cerebral, multi-armed Ponderous Complexicator,...

Helvetica: A Feature Length Film About a Typeface

After working in book publishing and producing numerous feature documentaries, a...

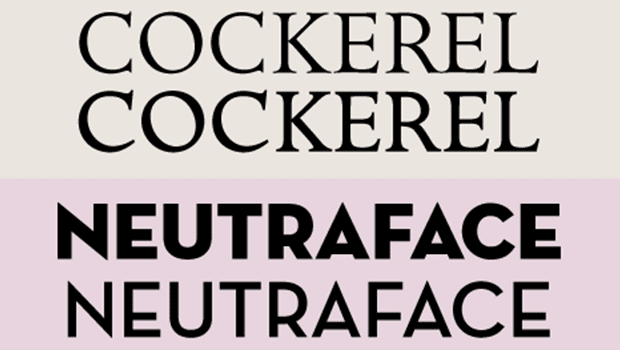

TypeTalk: Titling Fonts and Titling Alternates

Learn how to use titling fonts and titling alternates to add personality and ele...