Under the Desktop: Writing the Safety Rules for Recordable CDs

To learn more about data archiving and image preservation, come to David’s session “Archives for the Ages: Preserving Your Images and Data” at Seybold San Francisco, September 8-12, 2003.

Peering into the mailbag, I recently found an item about the durability of CD-Recordable media. Content creators like audio-conscious consumers are familiar with burning discs, and think we know everything there is to know about the optical technology. However, there’s a big difference between shuffling some MP3 cuts for a buddy (yes, it’s wrong, wrong, wrong) and storing your digital images and business records for the future. Or even sending a client a portfolio on disc.

Reader Bob McColley, who teaches a class on digital photography in Sun City, Ariz., related his recent experience with CD-R discs and posed a question:

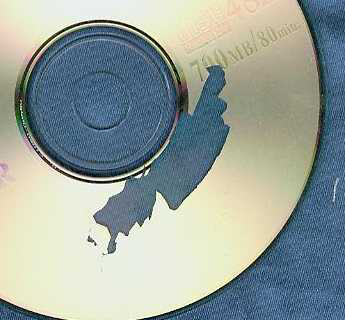

“I always assumed that CD-R [discs] were about as safe as Fort Knox, barring scratches or breakage. That is until this happened to one of my CD-Rs [See Figure 1].”

Figure 1: Here’s a photo of McColley’s disc. The key thing to observe is exactly how the disc is damaged. Something has apparently struck the disk and gouged through the top surface of the media and into the opaque gold foil below. This is why we can see through the disk into the blue cloth underneath: an area of the reflective layer has been removed. In the optical media industry, this is called “delamination.” Whatever it’s called, your data is hosed.

Figure 1: Here’s a photo of McColley’s disc. The key thing to observe is exactly how the disc is damaged. Something has apparently struck the disk and gouged through the top surface of the media and into the opaque gold foil below. This is why we can see through the disk into the blue cloth underneath: an area of the reflective layer has been removed. In the optical media industry, this is called “delamination.” Whatever it’s called, your data is hosed.

“This CD was mailed to a friend and was well padded for mailing. I couldn’t understand what my friend was trying to describe to me so I had him return it. Now I’m inclined to think my data isn’t safe without duplicate CDs and stored in different locations (against the threat of fires, floods, etc.).”

“Have you seen this type of damage before? I’ve never seen any reference to the possibility of this kind of damage. Don’t you feel that the possibility of this kind of damage should be widely publicized? I believe most people feel that once their files are saved to a CD-R they are safe for the ages.”

Many of you, no doubt, share McColley’s assurance about CD-R media. And as I’m moderating a panel at Seybold San Francisco about archiving methods, I’ve been doing some research. What you need to know is that despite that confidence in CD-R, your data is far from safe.

Under the Substrate

Confidence with CD-R media is based in part on our past, positive experience with earlier CD-ROM technology as well as from the hype we receive from companies selling writable and rewritable optical drives. And as usual, it’s necessary to bring these subjective impressions and marketing claims into line with real-world expectations.

While CDs and CD-R discs are almost identical in appearance — they are same size and thickness, have holes in the same place, are shiny, and can be played mostly in the same machines — the two media have important differences, in their technology and manufacturing process.

Figure 2: The exposed layers on the right-hand side show the layers of a CD-ROM disc, while on the left is a CD-R disc. This illustration by Sony is very good at showing the pits and grooves inside the disc. However, most other illustrations more accurately divide the CD-R’s bottom blue layer in two: one towards the middle is a very thin layer of dye and the larger lower layer of clear polycarbonate plastic, which provides protection. Note that CD-Rewritable discs add another layer or two, yet more tweaking of the physical format.

Figure 2: The exposed layers on the right-hand side show the layers of a CD-ROM disc, while on the left is a CD-R disc. This illustration by Sony is very good at showing the pits and grooves inside the disc. However, most other illustrations more accurately divide the CD-R’s bottom blue layer in two: one towards the middle is a very thin layer of dye and the larger lower layer of clear polycarbonate plastic, which provides protection. Note that CD-Rewritable discs add another layer or two, yet more tweaking of the physical format.

A CD-ROM (or DVD for that matter) is a mass-produced, printed item. The information is stored in an incredibly long, thin spiral of tiny bumps (the underside of a bump is a pit) that wind around the disc. The spiral starts on the inside and works its way towards the outer edge.

When laser light is shined into the disc, it bounces off a thin, reflective sheet of metal, either aluminum, silver, or gold foil, and the optical sensor reads the reflective differences created by the bumps and then interprets those blips as bits of data. If you want to know more technical details of the process check out the long article on the subject at How Stuff Works.

On the other hand, a CD-R disc is created on the desktop rather than at a plant. The spiral line of data is recorded into a thin layer of photoreactive dye sandwiched between the reflective metal foil and polycarbonate plastic. The dye creates pits that mimic the bumps of the mass-produced discs.

So far so good. But as we all know, discs can be finicky.

The Delamination Proclamation

Of course, all of the layers on a disc are very thin, some measured in nanometers, since the platter is only 1.2 millimeters thick. The dye layer and the reflective layers are especially thin and fragile when exposed. Failure of a layer is called delamination in the optical drive industry.

Most of us are concerned with contamination or damage to the shiny underside of a disc, where a scratch or even a fingerprint can scatter the light from the laser bringing a hiccup to the transmission of data. Most of these problems can be fixed with a spray cleaner designed for polycarbonate plastic and optical cleaning cloths. For some serious scratches, vendors offer polishing kits that can erase a scratch by smoothing down the protective polycarbonate layer. Frugal users suggest a low-cost alternative: abrasive toothpaste and a Q-tip.

However, we don’t often consider that the top of the disc is also vulnerable; or perhaps even more so than the bottom side, since damage to the reflective or dye layers can’t be repaired with polishing or cleaning. If they are compromised, the data will be lost.

In addition, the bonds between the layers of a CD-ROM disc are stronger than a CD-R disc, so there’s more of a chance for delamination failure in the writable discs. Worse, the layers in the CD-R (and CD-RW) disc are thinner, also offering more possibility for failure.

If a disc is delaminating, or suffers a small puncture, sometimes making a paper CD label and applying it to the top surface of the disc can prevent further problems; this can a stop-gap measure while you transfer data from the damaged disc to a new disc or hard drive. A paper label also offers basic protection of the top surface. I like the Discus labeling software by Magic Mouse Productions for Windows and Mac OSes. The software also supports almost all commercial paper labels on the market.

While we can feel good about protecting our discs with paper labels, that strategy brings its own share of problems when evaluating the stability of the disc. The glue in the label can interfere with the varnish-like coating on the top of the disc. Removing the label is also problematic, since it can pull off parts of the top coat and perhaps even some of the critical foil layers underneath.

So users need to examine the use they will make of a disc when considering its handling. A label may protect a disc — who knows, it might have saved the disc Bob McColley sent through the mail — but could bring other problems for long-term storage.

Care and Feeding of a Disc

So, how long can a disc last? Or more importantly, how long can the data that’s on the disc last?

It’s difficult to determine. There’s a vast difference between the hypothetical longevity determined by statistical methods from a small sample of media in a test lab and the discs sitting in a pile on your desktop. Obviously, the latter figure counts more for you and me.

Some manufacturers claim that discs can last 100 years or longer. Other groups give figures in the 25-to-50 year range.

All of these targets seem very optimistic to me. The estimates are based on unrealistic, pampered handling of media. For example, the CD standards groups advise storing CDs much like red wine, at room temperature, around 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit). As if.

As mentioned before, beyond the failure from scratches and mishandling, the discs can suffer degradation from various environmental causes including high humidity and temperature and the exposure to sunlight. All of these factors can occur in “normal” use of the media, so this wear-and-tear must be weighed against the theoretical best-case storage situation.

Certainly, CD-R discs should last at least 5 years, which is a good conservative time span. This is the lower figure from some data preservation organizations, which range up to 10 or 15 years. For archival purposes, I suggest you migrate data from one CD-R to a fresh copy every five years or so. This will ensure the integrity of your data.

Here are a few additional tips for keeping your CD-R discs (and your data) in tip-top shape:

- Store the discs in a sturdy container such as a jewel box. Its extra protection will guard against nicks and scratches.

- Keep at least two copies of a disc and store each one in a different place. You should never have just one copy of any data file.

- Don’t use paper labels on archival discs. Adhesives can chemically degrade media and become unstable over time. And never attempt to remove a label.

- Heat is a big problem for CD-R/RW media. The maximum temperature when recording a blank disc is 55 degrees Celsius (131 degrees Fahrenheit) and the maximum “operating” temperature for a recorded disc is 70C or 158F degrees, respectively. Consider that the ambient temperature inside an automobile can rise beyond 140 degrees (60 Celsius) in an hour and the surfaces inside can climb above 160 degree (70 Celsius). That’s no good for your data if a disc is on the seat or in the trunk. (Imagine what it’s like for children and pets!)

Data safes are available from a number of vendors. These products are designed specifically to keep media temperatures within a safe range for a period of time, and are a good place to store a primary archive. Depending on the model, the safes can protect the files on discs for up to several hours in the worst of fires. However, they are expensive. costing between $2,500 and $4,000. A low-cost alternative is a media vault, or a digital strongbox, which can be had for under $400.

I suggest that professional content creators relate the preservation of data to their health. As expressed by the great medieval rabbi Moses Ben Maimon (aka Maimonides): “The purpose of maintaining the body in good health is to [make it possible to] acquire wisdom.” The purpose of maintaining your digital archive is to for you to acquire images and keep your clients.

David’s right to bring the attention of everybody to the life span of CDs. Researchers in Spain also maintain that CDs can be degraded by fungal attack. So, the correct temperature for storage COULD have a bearing on their life span – but who’s going to bother? A few years down the track, there’ll be cries of “WHY didn’t somebody tell us this could happen?” Of course, it would be too much to ask that a manufacturer produces a well-resarched, quality product to start with? And who hasn’t gone out and bought the 50cent CD, rather than that expensive $1.50 one? “They’re all just CDs.”

I usually save important videos on CDs (like birthdays, baptism, family bonding) esp. for a non-millenial people like me. I’m trying to fix one of my CDs and search through many websites to save the unripped part of it.

please. HELP!