The Darkroom Makes a Comeback

A few years ago, the computer age allowed photographers to escape the darkroom. Ironically, newly released, rigid viewing standards are pushing the photography, graphic arts, and publishing industries toward the need to lower the lights for entirely different reasons.

It’s not uncommon for desktop publishers in corporate environments to set up digital imaging computers in offices awash in fluorescent and window light. That approach, after all, saves money. But it does so at the expense of precise color image editing. Seasoned color editors agree that the most effective work space for critical computer editing of photography actually is a specially designed, darkened room — in which the overall illumination is lower than the brightness output of the computer monitor.

Attaining the ideal setting also necessitates considerations beyond lighting levels. To begin with, windows should be either heavily shaded from outdoor lighting or omitted outright to maintain a constant level of illumination throughout the work day. Next, to prevent ambient conditions from affecting human color perception, daylight-balanced D50 (or 5,000º Kelvin) fluorescent or filtered halogen lamps should be used for illumination. Ideally, walls and ceilings should be painted a neutral gray; and even flooring, countertops, and monitor faceplates should be color neutral. If the conditions for editing and viewing digital images are not rigidly controlled, the most subtle changes in color, brightness, and contrast displayed on a computer monitor may be impossible for the human eye to distinguish.

Standard Viewing Conditions

Following recommended standard viewing conditions is important to ensure not only accuracy in color imaging, but also consistency. Standardized color-imaging facilities allow different companies (or departments within an organization) to analyze, edit, and process files with consistency and eliminate as many variables as possible.

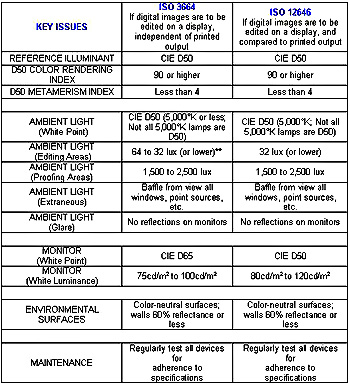

On September 1, 2000, standard viewing conditions for digital imaging production facilities were updated for the desktop imaging age. The revised international standard, called “Viewing Conditions — for Graphic Technology and Photography” (otherwise known as ISO 3664:2000), was created by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). The ISO is set to release a second, related standard — ISO 12646 — by spring of 2002. Together, the revised standards have far-reaching implications.

The exhaustive, 20-page ISO 3664:2000 already available defines ideal viewing conditions when digital image files are displayed on a computer monitor in isolation, independent of any form of hard copy. In contrast, ISO 12646 (“Graphic Technology — Displays for Color Proofing — Characteristics and Viewing Conditions”) reasserts tighter (and long-used) color pre-press viewing conditions for monitor calibration and room lighting. In short, if you are setting up a contract-accurate imaging lab for comparing digital image files and printed output, then follow ISO 12646. If you are a Web developer or desktop publisher who seldom produces contract-accurate, printed proofs, you can use the less rigid IS0 3664:2000 as a guideline for setting up a color editing system.

In addition to defining a minimum standard for computer viewing, ISO 3664:2000 defines the optimum conditions for viewing images reproduced on reflective media such as photo prints and press reproductions, and on transmissive media such as photographic transparencies. It also establishes illumination levels for viewing, exhibiting, and judging photographic prints (directly) and transparencies (directly or by projection).

ISO 3664:2000 also identifies a reference illuminant for room lighting known as CIE D50 (lamps with a relatively even spectral power distribution, similar to 5,000°K). D50 is based on yet another global standard set by the International Commission on Illumination (CIE). In addition, the ISO standard also defines desired ambient illumination levels and surround conditions (such as window light and neutral colors for walls, floors, and ceilings). And it recommends calibrated displays with specific white-point (D65) and white-luminance (75 to 100 candela per square meter) settings. ISO 3664:2000 even defines ideal surround conditions (such as transparency border and monitor faceplate color values) and warns against poor environmental conditions, such as colorful, distracting background areas in a monitor’s field of view.

Dimming the Lights

However, it is the ISO 3664:2000 standard for proper lighting in rooms where monitors are located that may shock desktop publishers and prove controversial in corporate settings, because it could be costly to implement. Imaging computers set up in brightly lit offices will be most affected: Under ISO 3664:2000, reduced ambient illumination in editing areas is the goal, and “shall” be less than 64 lux but “should” be less than 32 lux. ISO 3664:2000 standards are specified as either “shall” (a requirement that must be met) or “should” (a strong recommendation). Of course, the ISO isn’t going to send troopers to storm your office if it learns you aren’t meeting its requirements. But for organizations that build their reputations on ISO compliance or have such compliance written into their contracts, these requirements matter.

Some might classify 32 lux as working in darkness. Even a 100-watt, soft white, incandescent reading lamp in a room with no other illumination, off-white walls, and low ceilings measures about 350 lux at about two feet from a shaded source. Photographers accustomed to chemical darkrooms with far lower illumination levels will easily adapt to this way of working. However, typical office workers are accustomed to a relatively bright illumination level as high as 750 lux.

Corporate managers may cringe at the cost of reconfiguring office space to set up image-editing computers in rooms with lower levels of illumination. The reality, however, is that it is much easier to perceive color accurately and to make critical color adjustments when room lighting levels are lower. The ISO maintains that following lighting guidelines invariably results in fewer color output errors, which in turn reduces production costs.

Stricter Still

The ideal viewing conditions to be established in the upcoming ISO 12646 standard actually define a more rigid white-point (D50) and white-luminance (80 to 120 candela per square meter) monitor calibration standard, which can be met by most professional displays. It also specifies even lower room-illumination levels (32 lux or lower) that should be used when displayed digital image files will be compared to printed output. Ultimately, ISO endorsement of dueling monitor viewing standards reflect the reality that desktop

publishing and pre-press committee members were never going to agree on a single standard, because no one proposal met the diverse needs of all computer users. In other words, ideally, all of us who are concerned with color accuracy would be conforming to ISO 12646, but ISO 3664:2000 is a good compromise solution for businesses and individuals that don’t have a lot of money to throw at a solution.

The most important lesson graphics professionals can learn from studying these two complex new standards may be just how important proper lighting and other ambient room conditions can be in the production of accurate, consistent color. For others, including aging photographers like myself, that means a return to the darkroom. One can almost smell the chemicals.

In part 2 of this article, we’ll continue with practical tips for getting your office up to snuff for color-accurate work.

Read more by George Wedding.

it would be awesome if the article could be updated with a larger viewable version of the “ideal digital studio” panoramic photograph. The current picture is too small to see details. A larger version would give more clues as to lighting techniques, light placement, and would give people some ideas about what, exactly, makes an efficient, comfortable work space given the article’s guidelines.

I am a print professional, and wherever I go, its easy to tell who is and who is not serious about color. Those that are have painted their studio walls 18.5% gray and have all the lights turned down low, usually with a small light-checking box at each station to check proofs with. The places that dont really care make you work under normal flourescent lighting and dont provide tablets to work with, thinking that you can get the same sensitivity with a mouse. one place thought I was some kind of freak when I brought my own Wacom in.

Also, I disagree with the previous comment on this article: read the article if you want to know what to do. If you just want to look at the pictures and try to figure out what to do, you’re in the wrong place.

A note from the author:

Part 2 of this report will be posted soon, and it offers ideas for purchasing and installing the proper lighting equipment in image editing rooms.

We have added a QuickTime VR version of the example “digital darkroom,” which lets you look about the room and zoom in and out. We intended to post this with the article to begin with but ran into technical problems.

Thanks to all for the feedback!

Mitt Jones

Senior Editor, creativepro.com

I’ve been following guidelines for proper monitor and ambient light D50 suggestions since 1990 or so, and it’s cool to find everything we’ve ever thought about and tried all in one place with George’s article. Especially since it’s so well balanced — no stringent insistence on ISO when it doesn’t matter at all. (I was a bit peeved to see that ISO is charging for the standards information which should be free, as George and CreativePro have done. After all, ISO didn’t do the work of the last decade in color viewing conditions.) Especially, I find so sensible the suggestions to use alternative, economical alternative light sources, N8 paint formulas and near D50 lamps. After all, with 30 workstations one can hardly afford the stuff sold by my good friend, Fred McCurdy of GTI. If ever we are going to get customers and creative services to use correct viewing environements, it’s got to be within the budget, at least to start with.

Thanks to you, George and to CreativePro

Tom

thanks for sharing valuable information

Even 32 lux must be nicer than the smell of the chemicals (especially the stop bath if you’re into black and white) and in my case working under the light of a couple of red LEDs. :-) Such are home made darkrooms.

I’ve had a go at setting my home system up. Room lighting is very low – a halogen in the next room spilling in. Following the instructions that came with my “Spyder 3” I set my monitor to 5000K, 90cd/m2, which is warmer than I’m used to seeing it.

Colour really seems so subjective. If I “soft proof” a file I sent to a photo lab, then go look at the print under halogen light, then the match looks quite good. If I turn on the halogen room light and place the print next to my monitor it still looks pretty good to me, but to a camera it looks far off with the monitor blue. I guess my eyes adjust where the camera does not?

My first impression looking at the print under daylight and also under a daylight flourescent was that it was slightly cold – so I have a system that seems to be able to give me a good impression of what a print will look like if I send it to the lab then look at the result under halogen light, but taking the same print and looking at it under different light changes things.

Is it worthwhile my trying running my monitor at 6500K? The slightly bluer light (assuming my eyes don’t compensate) would presumably give me a better impression of the photo I get assuming that I mostly look at photos in the daytime?

Thanks

– Richard

There are some suggestions for actual screen brightnesses to try in the Room Lighting article, but my own monitor is currently set to ~110 cd/m2, 6500K and a gamma of 2.2.

I must confess, the color management with photography topic has always been a real source of frustration to me, I’m a photographer for real estate agent in indonesia Rumahku rumah dijual and in a way, it continues to be this way…

The problem is, there’s no way I can get a picture to look the same, or even roughly similar in the print and on the monitor. These are simply two very different worlds. In order to look good on screen, I have to use a profile provided by the screen manufaturer (Samsung in this case). This profile guarantees a correct rendering of all the shades, and a decent gamma. With this profile, photos that are taken directly from my camera, as well as most websites, and professional photos found on the web, look all good. Also, printing photos on a cheap ink printer, presents no problem.

However, when I do a work (photos alone or

photos combined with vector graphics) with an intent of printing them on

a big industrial CMYK printer (like Heidelberg), and I use the same

manufacturer’s monitor profile, the results are terrible: my fotos come

out dark, and the details in the shades are all gone. Well, this is

where my Spyder2Express monitor profiler comes in. The profile it

creates is completely useless for the normal use (images come out way

too dark), but it corresponds with the profiling of industrial printers.

When I instal that profile, the dark images on the screen are finally

similar to the dark images that came out from the industrial press. So

now, I can prepare my photos for the CMYK print by brightening the

shades with Photoshop’s curves or “shadows/highlights” command. This way

I get what I want (well, more or less so) on the industrial press.

This is what I normally do, but I’m not totally happy with that. First, it’s

a double work to prepare two different versions of each photo, second,

photos loose their original quality by unnaturally stretching their

dynamic range in the dark parts (they may get more noise in those

parts), third, you’ll never get a photo exactly the same as it was in

its original state (i.e. viewing with the manufacturer’s monitor

profile) – the original gamma “linearization” is hard to replicate with

Photoshop commands. I guess, all that work should be done by the

profiles themselves, after all this is what they supposedly exist

for:)…

Also, I disagree with the previous comment on this article: read the article if you want to know what to do. If you just want to look at the pictures and try to figure out what to do, you’re in the wrong place.

good to know this. thanks for the information.