Remote Collaboration with InDesign

Collaborating on documents is crucial for creatives. InDesign and InCopy make it easy.

This article appears in Issue 49 of CreativePro Magazine.

During my graphic design and prepress apprenticeship, we overnighted hardcopy proofs to clients who marked corrections by hand and then returned the galleys and bluelines the same way. When we needed to exchange digital files, we shipped removable hard drives back and forth.

Now, InDesign and InCopy enable instant (or near instant) file sharing, collaboration, and proofing—no printing, FedEx, or drive-compatibility anxiety required. Whether you’re a digital nomad with a MacBook or desk-bound with a beige box chassis, these tips will help you package your files for sharing and streamline your collaborations.

InDesign-to-InDesign Collaboration

The most basic type of collaboration is the simple handoff of your native InDesign documents to another person or firm also using InDesign. To do that effectively, you first need to employ the Package feature. The digital version of bundling all relevant material into a FedEx envelope, Package copies the document and all the digital stuff it needs—fonts, images, and other linked assets—into a single folder in one step.

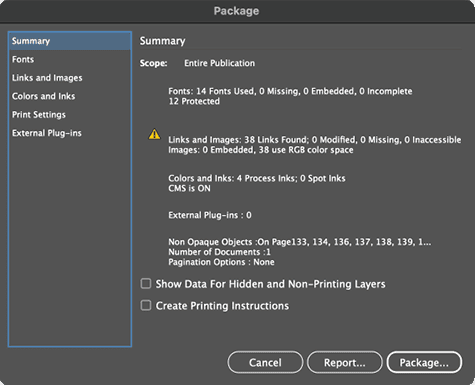

Choose File > Package to open the Package dialog box (Figure 1). There, the Summary tab shows you details about your document, from its fonts to the status of its images, from the inks it uses to its overprint settings. You’ll even be able to tell if the ability to edit the INDD document is dependent upon third-party plug-ins, which is less of an issue now than it was in the early days of InDesign but still relevant. If any errors or potential issues exist, you’ll see them flagged here with a caution icon.

After ensuring that nothing is missing, click the Package button. InDesign will then ask you where to save the package folder, into which it will save a new version of the INDD file and a Links subfolder, at minimum.

The Links folder will copy all the linked assets (images of any kind, as well as linked Excel, Word, RTF, and TXT files, or other files that are linked in your document), leaving your originals untouched. InDesign will also update the new INDD document to point to the assets in the Links folder rather than to the original files in their original locations.

Your package may also include a Fonts subfolder, which will contain any fonts used in your document, except possibly for the following:

- Fonts from Adobe Fonts. These are, theoretically, available to any collaborator… except if those fonts have been removed from Adobe Fonts, but that’s a whole other conversation.

- Fonts installed using a local font manager as temporary activations. Most font managers—RightFont, Extensis Connect, and others—allow you to activate fonts permanently or temporarily. Temporary activation can interfere with InDesign’s ability to copy those font files to a package.

- Fonts that aren’t allowed to be copied and shared with collaborators. The vast majority of fonts are allowed to be copied and shared under certain very strictly limited conditions—such as when packaging an InDesign document and sending it to a printer or prepress house so that such vendors don’t have to essentially pay for every typeface and font version ever made. A few type foundries, however, do not allow their fonts to be shared for any reason. They usually set the option inside their fonts to disallow packaging. As a responsible member of the creative industry, Adobe respects that “not allowed” switch and prevents InDesign from copying such fonts. The only solutions to that situation are either to use a permitted font or require your collaborator to license the typefaces.

- Font version mismatches. Fonts are software. Software has versions. The filenames of different versions aren’t necessarily different. So, if your document uses both Helvetica LT Std Roman version 2.030 and Helvetica LT Std Roman version 1.86, InDesign will likely be able to copy only one of them to your package’s Fonts folder, resulting in a missing-font warning for anyone who opens your document without both versions of Helvetica LT Std installed.

Additionally, you can instruct InDesign to generate other versions of your INDD document—IDML and/or PDF—during the packaging process (Figure 2).

An IDML version lets your collaborators use earlier versions of InDesign.

You can also tell InDesign to generate a press-ready PDF using any of your PDF presets—most commonly, to send your file to your print provider. The printer would use the press-quality PDF unless there was a problem that needed to be fixed within the INDD directly, in which case, thanks to the package, they could open your source file and not be (in theory) missing files.

I also always include a PDF version in my packages when archiving a project. This ensures that even future non-InDesign users will have a view of the document and a fundamental reference if they ever have to recreate the layout using different software.

Collaboration Between InDesign and InCopy

What is InCopy? Fundamentally, InCopy is InDesign for editors, with many identical features, but some abilities removed (like the ability to create and move frames) and other editorial- and writing–specific features added (like text macros, a thesaurus, and several ways of working within any given story). InCopy is ideal for giving writers and editors control over the text of stories in the context of a document’s layout, even while a designer continues to work on that same layout simultaneously in InDesign.

If you send an INDD document, either by itself or in a package, to an InCopy user, your collaborator can open and read (but not edit) the InDesign INDD document directly in InCopy. If the package includes the ICML (InCopy Markup Language) files that InCopy uses, the reviewer also will be able to edit the content of those stories.

InDesign export to InCopy

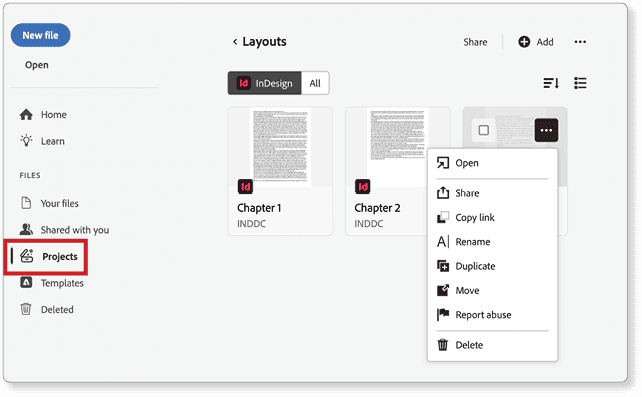

In InDesign, choosing Edit > InCopy gives you the two methods of sending an entire document or parts of it to InCopy: exporting and assigning (Figure 3).

Using Edit > InCopy > Export, you can export selected objects, all objects on a layer, all stories in the document, all graphics, or all graphics and stories in the document to InCopy. These options will convert stories (threaded or unthreaded) and proxies of images to ICML files, creating links to them in your InDesign document. A designer can continue working on a design while an editor is changing text. If you export a selected story to ICML, an editor can work with the text in InCopy with access to the typographic controls of InDesign, including paragraph and character panels and styles, but no way to change how it is laid out on the page. The content can be changed only by one person at a time with either InDesign or InCopy.

InDesign assignment to InCopy

The Edit > InCopy submenu also offers options to add various types of content to an assignment, which is essentially a user-specific package of content for InDesign or InCopy users. First, you must create an assignment with the Assignments panel (Window > Editorial > Assignments) in InDesign. Then, using either the Assignments panel or the Edit > InCopy commands, you can add content to various assignments. Each assignment can be created for a different collaborator.

With an InCopy assignment file (INCA), your editorial collaborators can also see their story or stories in the context of the design. They can work within the geometry of the text frames and see (but not touch) the design and other text. When the InDesign layout is saved, the InCopy user can select File > Update Design.

InCopy saving to InCopy

Suppose you’re an editor, and both you and a writer use InCopy—the design team doesn’t want anyone fussing with their InDesign layouts. The easiest way to exchange proofs InCopy-to-InCopy is to choose File > Save Content or File > Save Content As. Both methods create an ICML file that any InCopy user can edit and that any InDesign user can place into a layout.

InCopy forwarding to InCopy

The Save Content method, however, lacks any kind of double-modification protection. In other words, as long as two people aren’t accessing the same ICML file from a network drive, they could both edit it simultaneously, which is a bad idea. To avoid such version-control issues, you and the writer could use the File > Package > Forward For InCopy command to send the document instead.

Forward For InCopy enables check-out/check-in functionality that prevents double modification. These collaboration options in InCopy provide a last-state protection scheme, meaning that if you check out a story and start editing and then lose connection, InCopy will continue under the assumption that you still have the content checked out, thus preventing anyone else from modifying the same content until and unless you check it in.

InDesign offers the same options, plus the ability to assign an InDesign user to override the check-outs. In both apps the check-out/check-in system gives you a safety layer; I almost always use it, especially with remote or long-distance collaborators.

Package InCopy files for InDesign

From InCopy, you can create or edit ICML stories and then send them to an InDesign-based designer, who can directly place those stories into InDesign. That process allows InCopy users to begin writing independently of whether an INDD has yet begun. For example, while you and the writer refine an article, the designer can already be working on a layout for it.

In addition to this write-first-layout-next approach, going from InCopy to InDesign is also often the culmination of the other methods of getting InDesign content to InCopy-based users. For example, both exporting to InCopy and creating an assignment for InCopy activates the two applications’ check-out/check-in functionality, allowing only one user to export or assign content at one time. Automatic synchronization of changes in both directions takes place once the user (in either InDesign or InCopy) finishes editing the story and checks it in: InCopy users are alerted to layout changes, and InDesign users see ICML files as modified links in the Links panel. In InCopy, modified layouts will be flagged as Out of Date in the document tab and the Window menu. Choosing File > Update Design will display the updated layout in InCopy.

The Return For InDesign option (File > Package > Return For InDesign) is a package–like method of permanently returning InDesign-initiated content back to the InDesign layout (Figure 4). Like the Forward For InCopy command, Return For InDesign effectively says “I, the current InCopy user, am done with my work, and now it’s on to someone else.” Content can always be sent back to that InCopy user, but those commands are generally employed when the InCopy user is finished, at least with the current editing round, and wants to send the content to a different team member.

How does it work?

The User Experience

Grade: InComplete

Passing Around Editable InDesign & InCopy Documents

Now that you know the different methods by which other InDesign and InCopy users can also edit the content you’re working on, the next question is how to get that content to those collaborators. Let’s look at a few methods.

Emailing files is the most obvious method of delivering files to each other. There are even variants of the Forward For InCopy and Return For InDesign commands that start emails from within InCopy. While InDesign doesn’t have built-in commands to initiate emails, INDDs, ICMLs, and whole packages can be emailed.

Note that I strongly recommend compressing a package folder, including all documents and subfolders, into ZIP archives before emailing them. You may also want to zip packages for some of the following delivery methods, too.

Shared network locations

If you work from the same office as your team, or are using a VPN or remote connection to access shared organizational storage and asset locations, you can certainly use shared network locations for collaboration. All you have to do is save a document or package to a shared network location, tell your team about that location, and then let everyone get to work. InDesign and InCopy will prevent two users from editing the same document at the same time. For example, if you’re working in an INDD document, and I try to open the same INDD, my InDesign will tell me I’m in read-only mode and can’t modify that same file. Note that this is a fairly flimsy double-modification prevention detection system; if you or I lose connection to the network share, even for a few seconds, our two installations of InDesign may not detect the other accessing the file. That would result in one of us probably saving over the changes of the other. Remotely accessing the shared drive dramatically increases the risk of that momentary disconnection and loss of double-modification prevention.

Cloud share live-connected content

Right up front I need to say that Adobe does not officially support or recommend collaborating on documents stored in cloud services like Box.com, Dropbox, Google Drive, iCloud Drive, OneDrive, or SharePoint. In fact, in most cases, Adobe specifically states they will not support files edited from such services, even by the same user. Adobe requires I say this because I’m currently (and have been for roughly 20-something years) a contractor or advisor (of one function or another) to Adobe I am obligated to explain the difference between my opinion and Adobe’s.

That caveat out of the way, please allow me to tell you my individual professional experience as a counterpoint. I’ve had cloud share doing real-time synchronization, backup, and version control of all my documents, InDesign, InCopy, Photoshop, Illustrator, and everything else, every document, since 2008. Every single document I work on—including this article as I write it—is being synchronized live by Dropbox to its cloud server, as well as to two other computers in my studio, and to my co-located backup servers in upstate New York and outside Dallas, Texas. Roughly every three years, Dropbox drops the ball and messes up catastrophically, deleting or corrupting… well… nearly all my important files, to be honest. But that’s why I have redundant (and non-Dropbox-based) backups and file versions stored using external servers and other (arguably more reliable) cloud-based storage services.

Still, I have never had an issue with InDesign, InCopy, or any other Adobe application—including system-intensive tools like Audition and Premiere Pro—losing links to collaborators or check-in/check-out connections and causing double-modifications.

Cloud share for transfer

If you don’t need live editing between team members, cloud share services are ideal and officially supported by Adobe (with caveats if the transfer doesn’t complete correctly, your internet connection drops packets, etc.). Are you sending documents from one person or team or location to another without the need for simultaneous editing or check-in/check-out? Then feel free to use cloud sharing services. Box.com and a few others offer HIPAA-compliant security, but if you don’t need that level of safety, just about any cloud storage service will work.

I use all cloud file transfer services (because, clients), but if you’re looking for large file transfer and don’t already have a cloud storage/synch service, I recommend MEGA, WeTransfer, and pCloud Transfer. Usually, I advise against using Dropbox for sending files to people who may not already have an account. While upsell-desperate Dropbox does allow you send files to non-users without requiring them to have their own Dropbox accounts, it makes many non-users think they can’t download your files without signing up, so most recipients do not download your Dropbox-shared files.

Universal View and Review

Rather than send original files to a collaborator or your distant client, modern technology enables digital proofs to be reviewed and marked up onscreen, often with accountability features such as tracking who made what change.

PDF reviews with In-InDesign comments

PDF files and PDF-based reviews are not new, but what still surprises me is how many InDesign users don’t know about the direct integration between PDF reviews and InDesign.

Here’s a common scenario many people use:

- Create a layout in InDesign.

- Export from InDesign to PDF.

- Email the PDF to clients, collaborators, SMEs (Subject Matter Experts), and other stakeholders.

- Get a bunch of emails back with, each with a commented PDF attached.

- Save all the PDFs to a folder.

- Open the PDFs one at a time, or even all at once, and then one at a time go through the comments and change requests on one monitor while the original InDesign layout is open on another.

- Jump back and forth between Acrobat and InDesign, comparing each change request in each PDF against each InDesign page, Command+Tabbing/ALT+Tabbing back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, back and…

Please don’t do this! You have several better options. Also, there are variations on the procedures described below in case your organizational security policies prevent you following these exact steps. Those variations are easy enough to find, so here’s the ideal step-by-step for sending an InDesign document for review via PDF.

- Export the InDesign document to PDF as normal.

- Open the PDF in Acrobat. Better yet, activate View After Exporting in the Export To PDF dialog to automatically open the resulting PDF in Acrobat without having to go searching for it.

- In Acrobat, choose… Ugh! Man, as an educator and consultant tasked with helping real Adobe users use Adobe software in real workflows, I absolutely detest Adobe’s process of rolling out Acrobat changes the last few years!

Here’s the deal. There are three interfaces to Acrobat you may be using if you’re using a recent version—the New Acrobat Windows (with the Menu menu), the New Acrobat macOS (with actual menus), and the classic (not-New Acrobat) Acrobat user interface many people prefer. So, instead of giving you three different click-here-choose-that-menu-command instructions, I’m going to refer you instead to Adobe’s equally confusing how-to.

Start a review using these instructions.

- When you begin getting reviews back, open the document again in InDesign.

- Go to Window > Comments > PDF Comments, which will open the PDF Comments panel introduced in InDesign 2018 and rarely promoted since.

- On that panel, click the Import PDF Comments button, and navigate to the first commented PDF.

- Now, with those comments and other markups in the PDF Comments panel, you can move between each comment—and corresponding page—directly in InDesign.

Publish Online: Review in a web browser

What if some stakeholders don’t have access to InDesign or InCopy? How do you get your content to collaborators? Publish Online.

A frictionless collaboration method that’s included with your Creative Cloud subscription, Share For Review doesn’t require others to have InDesign, InCopy, or even Adobe Reader. All reviewers need is a web browser to review the fixed-layout, ebook-like presentation you share. It can be viewed on any computer, on any mobile device, and can (at the InDesign user’s discretion) accept comments or merely be viewable.

To create this kind of simple, software–independent view or review of your InDesign document, follow these steps:

Open your InDesign document, and make sure you’ve saved any changes.

Choose File > Publish Online.

In the Publish Your Document Online dialog box (Figure 5), set such options as title, description, page range, and so forth. You can even activate password protection to allow only authorized users access to the document proof.

On the Advanced tab, configure the quality as well as whether users are allowed to download a PDF version of the document, and at what quality.

If desired, use the Analytics tab to connect a Google Analytics account to measure interactions with the document.

Click Publish, wait a moment or two, and then view your publication online as your clients, stakeholders, and other interested parties might see it.

Copy and share the URL.

Use the File > Publish Online Dashboard to unpublish or otherwise manage your software-independent preview. You can also unpublish if from that command, which is exactly what you need when the review period is closed.

A Fab Collab

It’s fabulous how far the tools for collaboration have come. The days of overnighting printed proofs and shipping hard drives back and forth are long gone. Today, we can work with remote colleagues as if they were in the next cubicle, editing files and sharing them for review, so stakeholders can provide feedback from anywhere in the world.

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Making Forms with InDesign and Acrobat Sign

Use text tagging to take your forms to the next level of functionality.

InDesign Magazine Issue 98: Animation

We’re happy to announce that InDesign Magazine Issue 98 (June 2017) is...