PDF and Panther: The Hidden Role of PDF in Mac OS X 10.3

For more information about The Seybold Report click here.

For the world’s publishers, Mac OS X is a blessing — no question about that. Publishers have never had an operating system that is this fast and this publishing-oriented. OS 9 users may not want to hear it (in some cases, they may have to be dragged kicking and screaming to OS X), but they, too, will soon learn to appreciate the advantages of OS X.

A few months ago, Apple publicly introduced the latest operating system release, version 10.3, code-named "Panther." It no longer relies on Display PostScript for its display format (as did the NeXT operating system — here one clearly sees the influence of Steve Jobs) but rather on PDF technology. PDF is one of the internal graphics formats; it is used in the "Quartz" module of the OS, which is responsible for 2D graphics.

This has the important result that it is no longer necessary to have any additional software to create and display PDFs. But don’t jump to any conclusions; as we’ll discuss below, this capability is largely irrelevant for printing and publishing applications.

Another major innovation of OS X compared with other operating systems is how closely it dovetails with the integrated ColorSync color-management technology. ColorSync provides support for accurate color display and for working with ICC profiles.

Great for Viewing, Not Output

Even though the Apple PDF applications depart from the familiar working methods of Adobe’s family of programs, many users from the publishing industry will likely depend more heavily on the Apple-supplied technology than on Acrobat Reader. The OS X viewer, called Preview, opens even enormous PDF files very rapidly. Preview facility is much superior to Acrobat when all you want is simple viewing and navigation through PDF files. For example, Preview requires only 2-3 seconds to launch, and it can open a 200-page PDF document in just 2 more seconds. Immediately after that, the full-text search facility is available. It works without indexing, but it is nearly as fast as the index-based Acrobat search. A list of hits (with links to the corresponding points in the document) appears within 10 seconds after entry of the search string. Integrated tools for the selection of text and graphics permit the program to be used as an "intelligent" intermediate format for the rapid transfer of information between files. And none of this requires generating an index in advance.

After a normal Acrobat installation in OS X, Acrobat always launches as the viewer for PDF files. If you want Preview to be the default instead, you have to let the system know via the Get Info dialog box. Note that it is now necessary (in contrast to OS 9) to have the file name end with ".pdf." Not every element of a PDF file is correctly displayed in Preview. Transparencies, though, are shown correctly.

While Apple deserves to be complimented for this powerful little Preview tool, its choice of which PDF specification to support is less praiseworthy. While OS X 10.3 does support PDF up through version 1.4, including transparency, many features of PDF are not directly supported. This means that these functions are not displayed, and they do not appear in the printed PDF either. Missing features include annotation, video, and sound, as well as many functions that are urgently needed by publishers. One looks in vain for support for transfer curves and OPI comments, for example. The settings for the overprinting function are missing, as is support for Illustrator’s overprint mode. Trimbox, artbox, and bleedbox settings are missing, as are references to external files, Xobjects, alternate images, and XML tags. Even the use of JavaScript and form fill-in is missing.

Figure 1: Preview, a PDF rendering application that is part of OS X, is much better than Acrobat for simple viewing and navigation. For one thing, it’s fast. Here we’ve searched an unindexed 191-page document and, within 10 seconds, gotten our list of hits.

This is a bitter disappointment. In practice, it means that Acrobat is still an unavoidable necessity for professional display and output of PDF documents.

Tools for PDF Creation

Not just the display of PDF documents, but their creation as well, has always been part of Mac OS X. Initially, using this was a risky business, but Apple learned quickly and now there are a number of tools available in the operating system that can be used to produce print-ready PDF/X-3 files. This is the second remarkable characteristic of OS X for publishers — PDF/X-3 creation directly from the operating system — and it likewise breaks new ground. Some of the tools are better than others, though.

Save as PDF: easy but dangerous. Once the PDF services have been activated (see sidebar at left), creating a PDF file from an application is simply a matter of selecting "Save as PDF…" in the print dialog. The PDF file is then created directly by the Quartz drawing module, which is also the module responsible for 2D rendering on the monitor. This dual responsibility is the source of the limitations of this method of PDF file creation:

- The quality of the image elements depends on the functionality of the application program. For example, it is possible to obtain only a 72-dpi image from an EPS graphic that has been placed in Word, since that is the highest resolution that Word itself can display.

- The situation is similar with color definition. Since the same routines are used both for PDF file creation and for screen rendering, colors in the PDF are specified as RGB only.

This method is very similar to the discredited method used by PDF Writer for PDF creation. PDF Writer is a tool that every publisher must prevent its customers — and above all, its employees — from using. For example, if you use PDF Writer, you can expect to lose all font information. If you still choose to use the Apple-provided functions built into the operating system, it is possible to produce a PDF that may be usable for printed output, but only if you can live with limitations such as those listed above. This is especially true when creating PDFs out of Microsoft Office.

Normalizer and ColorSync: better things to come? For PDF creation from professional layout applications or EPS files used in office programs, it is still necessary to take a PostScript-based approach, given that direct PDF creation is often insufficient. Apple’s developers recognized this and tried to provide a workaround. Apple integrated a reduced-functionality version of the Adobe Normalizer (see Note 1 at left) into OS X 10.3 so that PDFs could be generated from PostScript documents. Here, too, Apple stuck to the principle of "keep it small and simple." Alas! PDF creation is simple, true enough. All you need is an EPS or PostScript file and the Preview program. PDF generation is initiated by dragging the PostScript file onto the icon of the Preview program. PDF conversion starts immediately, which is indicated by a pop-up conversion window. A short time later (roughly the same time that Distiller would take), the file is ready. But the result is not very exciting, as you will see shortly.

The Normalizer module (the OEM version of Adobe’s Acrobat Distiller) is sold by various integrators and can be found in systems from Agfa, Creo, Heidelberg, and many others. But, in most cases, it is provided with a system-specific user interface and with significantly enhanced functionality. Generally, there are parameter settings that are specifically designed to work with the OEM product. Probably the most prominent examples are Prinergy, Metadimension, and Apogee, all of which have long used the Adobe Normalizer.

In Mac OS X, however, there are no user-controlled parameters available. They have all been predefined by Adobe and cannot be modified. So, for example, it is not possible to specify that images are to be downsampled or compressed. Colors cannot be changed, and transfer curves are simply deleted. So are overprint settings. When fonts are used, subsets are created starting from 1 percent; and if a font is missing, a warning is issued — but the PDF is still created. DSC comments, including OPI comments (important in many workflows), are likewise missing. Stepped gradients are not recognized and are therefore not replaced with smooth gradients, and Illustrator’s overprint mode is not supported. So this is definitely a bare-bones version of the Adobe Normalizer. Apple has not explained why it didn’t take this a step farther. The only thing we can think of is that Apple didn’t want to spoil its business relationships with other Adobe OEMs.

Publishers will just have to deal with the problem that PDFs created in this way can frequently reach formidable sizes, due to the lack of downsampling and compression. Fonts that are embedded as subsets can lead to repeated problems later in the workflow, especially when a piece of text urgently needs to be corrected shortly before the PDF goes to press or when several PDF files from earlier versions of a program have to be combined.

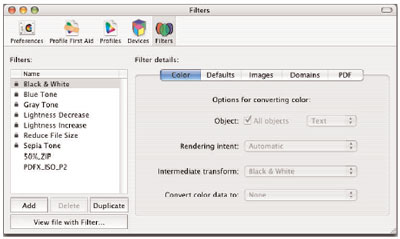

ColorSync and PDF creation. The Quartz ColorSync Filter provides tools with which PDF documents can be modified. If you think only in terms of color when you think about ColorSync, you will be shortchanging yourself. Behind the menus (which are somewhat awkwardly linked together) are hidden a number of practical functions. These can be logically separated into five areas: color-space conversion, image optimization, resolution adjustment, image compression, and PDF/X creation. But the settings for these options are remarkably well hidden from the normal user. The whole user interface is hidden away in the ColorSync service program.

Unfortunately, Apple seems to think that there is no compression except ZIP (also called LZW or Flate) compression. This is the only type of compression available for direct PDF creation. The ZIP algorithm gives significant compression only with "artificial" images (e.g., screen shots). But at least it has the advantage of being lossless.

It is also sad that every PDF created directly by the Quartz module in OS X 10.3 exhibits the "Generic RGB Profile," regardless of what ICC profile was set as the system standard. This means that, while it is possible to create PDF/X-3 files, no other color profile can be used. This is not exactly what the inventors of PDF/X-3 had in mind! In the current version of OS X (version 10.3.2), this must really be viewed as a "technology preview"; it suffers from problems of stability as well as lack of user-friendliness. What with one problem or another, we can only advise publishers not to use this tool.

Figure 2: Apple’s ColorSync does much more than adjust color. The PDF tab of this dialog lets you create various PDF/X-3 presets. They will then be available whenever you print, if you have activated the hidden services (see sidebar at left).

Creating PDF/X files in practice. Even though most of the items on a publisher’s wish list are only partially addressed by OS X, it is still interesting to explore how PDF/X files can be created via ColorSync. Apple will surely fix the problems listed above fairly quickly, and the principles (once you find the required menus) are really very simple.

The simplest way to create a PDF/X is by selecting it directly from the print dialog in the application (for example, MS Word). In this case, OS X creates a PDF file and deposits it on the desktop. If the user launches the ColorSync service program and then opens the PDF file via the Open dialog in the File menu, it is immediately displayed. The user is given access to a predefined set of functions, and it’s also possible to create a personal set. But to make the PDF file into a PDF/X file, a series of steps is required.

Figure 3: In the Panther version of OS X, Apple has greatly improved its PDF generation tools and now supports PDF/X-3 output. Because this is a function of the operating system, it is available to any application that can print, even if the application itself knows nothing about PDF.

First, the Images item in the middle drop-down menu must be selected. This gives the user choices such as sampling, compression and convolution. The "automatic compression" choice here would be ideal, if it were not for a program bug that allows only the lowest level of JPEG compression to be chosen. Another click back on the top menu takes the user to the "PDF" selection. There, under "Image interpolation," it is possible to activate bicubic downsampling. The next step is to select "PDF/X-3:2002" in the lower drop-down menu. There, "General Information" can be added — in the case of PDF-X, this can be specifications about trapping and about the trimbox and bleedbox. This is also where output conditions can be specified. (It is worth noting that the ability to specify the appropriate color profile would fit here nicely.) Under the "Target" item, it would be possible to specify the target profile, if Apple hadn’t left another bug in the code. At a minimum, it is important to at least note where the recipient can download the appropriate profile. (The PDF/X-3 specification permits this approach.)

Figure 4: A bug in Apple’s current code prevents you from specifying a target color profile. It is thus very important to indicate where your printer can download the desired profile.

Once all the settings have been made, it is only necessary to click on the Apply button and then save the file in a new folder.

If the user makes use of the predefined ColorSync filter settings, all that is required is to select the filter in the print dialog and then use the "Save PDF as…" function. OS X saves a temporary PDF file, converts this using the selected ColorSync filter, and deposits the converted PDF/X file in the desired folder.

These functions have already caused a lot of teeth-gnashing by various experts, a fact that the ordinary user may find comforting when nothing seems to work on the first try. But there are alternatives to this method of production.

Alternative Power Source for OS X

Users who want a better way of dealing with OS X should take a close look at PDF Enhancer from the U.S.-based vendor Apago (www.apago.com). PDF Enhancer, now in version 2.0 and priced at $180, offers downsampling and color-space conversion as well as a basic imposition function and options for encryption and for print optimization, among other things. Furthermore, the package can convert all gray elements defined in RGB to the grayscale color space, so that four-color blacks and grays are avoided in subsequent color separation. This is a problem that anyone dealing with PDF files from MS Office is familiar with.

Figure 5: Apago’s PDF Enhancer lets you define any number of targets (ours are listed in the left pane of the window) and, for each target, select the parameters that will optimize the file for its intended purpose.

The application of the software is very straightforward. The Enhancers (components) of PDF Enhancer each have at least one (in some cases, optionally more than one) processing step associated with them. A processing step (called a target) works with individual components of a document (or the document as a whole), based on settings that are arranged in different groups. This includes such things as downsampling and compression of images, conversion of RGB and spot colors, and a limited imposition function. It turns out to be useful to keep each processing step as simple as possible, and then combine several processing steps into a complex workflow. That way, you always have an overview of all the processes.

Once such a set of processes has been defined, the user has a number of options. The file to be processed can be opened in the application, a watched folder can be set up, or a "folder action" can be applied. Folder actions are a new feature of Panther. The action can be attached to a folder via the Apple Finder, and it will be launched every time the content of the folder changes. When multiple folders have to be monitored, this approach has the advantage over watched folders that the operating system doesn’t have to constantly check all the folders, resulting in better performance. Another benefit is that the application doesn’t need to run constantly in the background, since the system will launch it whenever the contents of the folder change.

But Apple has also provided broad workflow capabilities right in the Panther operating system, including "PDF Services." If the workflow described above is defined as a PDF Service, it will be directly available from the print dialog. When doing this, it is still important to specify in PDF Enhancer a folder for the file that is produced. Otherwise, it will be placed in a temporary folder that the user cannot access directly.

Figure 6: In Mac OS 10.3, you can create PDF services, folder actions and droplets using various system tools. Apago’s software offers a tool that’s purpose-built and easy to apply.

Acrobat 6: Still the Best Approach

As already noted, despite Apple’s efforts, publishers won’t be able to avoid using Acrobat 6.0 Professional. But shortly after installing Acrobat, many users notice that in addition to the many new functions in Acrobat, the relationship between the application and the operating system has changed. This is because Mac OS X is a multiuser operating system, with distinct settings for the system, the main user and other users.

After installation of Acrobat 6 Professional, you will see two programs, Acrobat and Distiller, in the /Applications/Adobe Acrobat 6.0 Professional/ folder (see Note 2 at left). More precisely, these are the installed program "packages." A package is actually a folder (though it cannot be opened in the usual way) in which all components required for the program are contained (e.g., the executable program, plug-ins, language-version files, icons, help files and default settings). To make Distiller settings files and start-up files available for all users, they must be located in /Users/Shared/Adobe PDF 6.0.

The Acrobat 6 plug-ins are also well hidden and may require a bit of a search. If you select the icon for Acrobat Professional 6.0 and open the Information window, you will find the plug-ins there. If the plug-ins are to be managed in a folder, a new folder must be created into which the plug-ins can later be placed. Following that, the program package must be opened, which allows the user to view the package contents via the Context menu. Next, the plug-ins folder must be located and an alias of the new plug-in folder placed there. After that, plug-ins can be installed and uninstalled in the usual way.

Difficulties with Distiller may also occur. These can result from overly restrictive access rights under OS X, such as situations where user B can only read (but not change or delete) files created by user A. Symantec’s tools (Norton DiskDoctor and Norton AntiVirus) are not without problems, either. If odd or unexpected problems occur during production, it is a good idea to check the access rights and change them if necessary.

These are relatively minor problems. The fact remains that Acrobat 6 is the only reliable, general-purpose tool for making print-ready PDF files under OS X. It is true that OS X has PDF facilities built right into the operating system, and that does hold out promise for the future. But the current implementation is just not able to address the needs of printing and publishing.

Conclusion

Mac OS X 10.3 isn’t always easy on the user, but it offers such an enormous performance boost that switching is unavoidable. It is still advisable, though, to handle PDF generation for prepress and print production in the "traditional" way. That will remain the case until Apple and Adobe make the Normalizer and the associated operating system functions a bit more suitable for use by print professionals.

What Apple has done makes sense as an effort to reinforce its position within the printing and publishing industry, but it also indicates that Apple is out of touch with the industry’s actual needs. In terms of useful functionality (or even user-friendliness) for the average user, Apple missed the mark with this initial effort. Nevertheless, it represents a first step, and we are eager to see what Apple does next in response to the many criticisms it has been getting.

Bernd Zipper is a business and technology consultant specializing in PDF, new media and cross-media publishing projects. His also the publisher of the German news site pdfnews.de. He can be reached at [email protected].

Peter Kleinheider is a workflow and PDF expert from Austria. As a writer for various industry magazines and for pdfnews.de, he imparts professional knowledge based on practical experience. He is also an expert in workflow automation and provides consulting and training services. He can be reached at [email protected].

I am thrilled to read this report in creativepro.com. This is the type of information that ordinary creatives would nfot regularly read.

The bottom line of this report is that the PDF creation in OS X, even in Panther, is sorely lacking any of the better controls that are found in real PDF creation software. Even FreeHand MX, which is still creating the same PDF 1.3 files it did almost ten years ago, is better in its support for features such as Comments which the Apple PDF does not support.

Looking at the larger issue, though, one wonders what Apple’s commitment to the graphics community is. Imagine if Microsoft had included this crippled version of PDF creation in Windows XP.

The Macintosh graphics community would be deriding the product as amaturish, a toy, ill-conceived, etc. But when Apple does a similar half-baked product, where’s the outcry? The Apple faithful are quiet.

What this article proves is that by omitting a user interface to control PDF creation, Apple has scrimped on providing an elegant PDF creator in Pather.