Heavy Metal Madness: The Family that Boats Together…

A Boat in Every Driveway

I know people still buy boats, and owning a boat is still a status symbol of some sort, but I don’t think boat ownership has the same feel it did in the 1950s and ’60s. Consumerism is more selfish now — we don’t really care what our neighbors think; in fact, we don’t even know who they are, so we buy more to please ourselves. But for a while there in the suburbs of mid-60s America, having a boat in your driveway was an important measure of success, and a wholesome form of family entertainment that didn’t take place in front of the television. The Kennedys tooled around Martha’s Vineyard in classic wood boats, young people water skied on each others’ shoulders during breaks from college, and docks sprung up on vacation homes everywhere. We and many others drove places for our vacations, so pulling along a boat was a common site. Many people, my dad included, built their boats to match their cars — in our case a 1956 Buick Roadmaster station wagon with rather large fins.

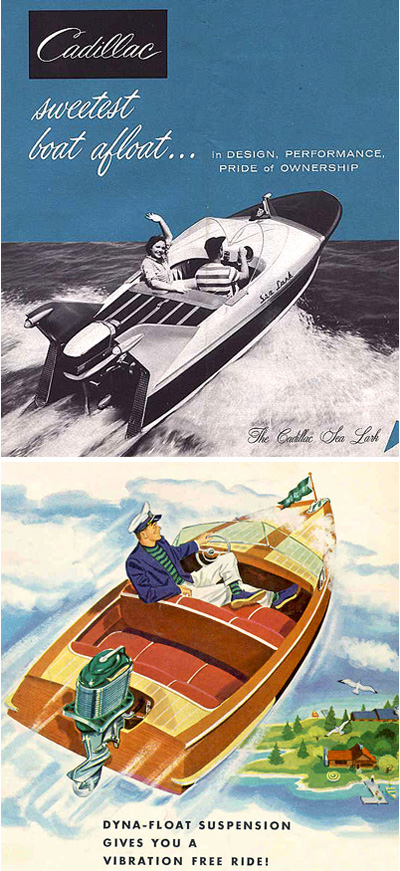

In 1959 Cadillac had not only the biggest fins on a car, but also on a boat (top). Using a Mercury Outboard Motor with Dyna-Float Suspension (bottom) was like flying on air when introduced in 1955.

Brands like Chris-Craft and Larsen had made wooden boats for many years, but they tended to be more expensive and harder to maintain — definitely more of a luxury item. The real growth in recreational boat sales came with the invention of Fiberglas and certain plastics that allowed for cheaper mass production. By the late ’50s there were hundreds of new small boat manufacturers, each with a unique look and styling. Some, like GlassCrafter, Glass Master, Glassflite, Glastron, Glass Magic, and my favorite, Fabuglass, played off these new manufacturing methods. Others, like Speed Queen, Thunderbird, Power Cat, and Slick Craft, went for image of speed and grace.

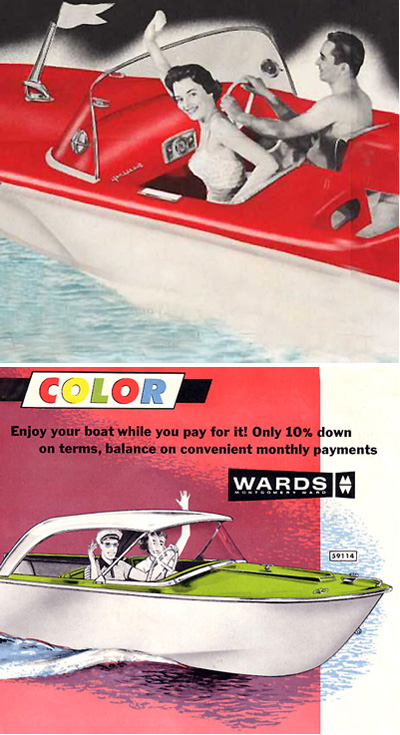

By 1959 when the Glasscraft Citation (top) was promoted, Fiberglas was the most common material used in small boat construction, and made an assortment of colors available, as highlighted in this ad from Montgomery Ward (bottom).

And then there were the motors, which on all but the largest of boats were add-ons, positioned conspicuously at the rear for all to see. The horsepower of your engine said a lot about your preferred boating activities. Fishermen needed just a small trawling engine so as not to disturb the fish. Water skiers and speed demons tended toward the larger models, and the ultimate display of power came in the form of matching twin engines moving together in graceful tandem as you turned the over-size steering wheels so popular in speedboats of the time.

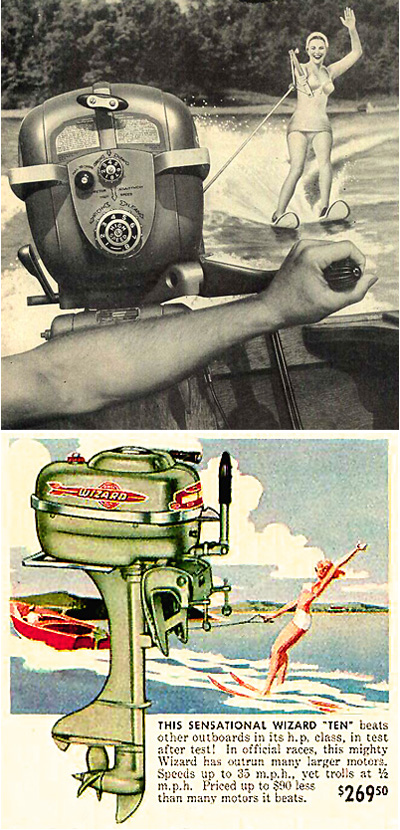

The Johnson Sea Horse was powerful enough to pull a skier in 1951 (top), and that same year you could buy a Wizrd Ten for only $269.50.

If you were lucky, your engine had an automatic starter that actually worked, and the turning of the key let loose the low, deep rumble so unique to large outboard motors. On the smaller motors (which tended to put out a conspicuous high whine), a pull-cord starter was more common, and the site of a frustrated boater desperately tugging at the engine was typical at any lake or seashore. This is when my dad cursed the loudest, I think, and one of the big breakthroughs for me in growing up was mustering enough strength to turn the engine over using this method. Thankfully, our electric starter worked most of the time, thus saving my arm and my parent’s marriage.

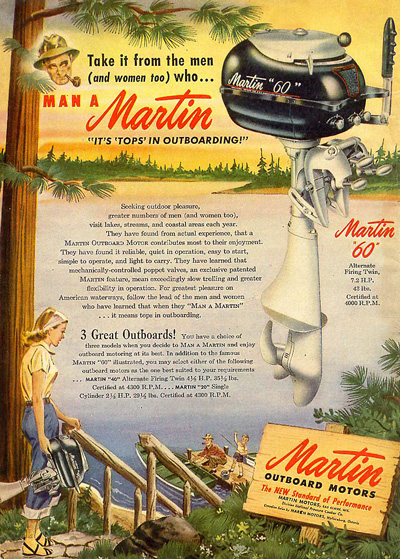

Martin outboard motors were light enough for even Mom to handle.

We had an Evinrude 40-horse motor, the brand founded by outboard motor pioneer (some say inventor) Ole Evenrude, who legend has it got frustrated rowing to show to get ice cream during a date with his future wife in 1904. The ice cream melted before he could row back, so he went home and built a gas-powered engine that could easily be attached to existing boats. The Evenrude company went on to invent the first power lawn mower, and thus captured another slice of modern suburban living (and also became the source of cursing training for young boys).

The 1952 Evinrude Lightwin weighs only 30 lbs and packs a big 3 horse power!

Other engine manufacturers (Whizzer, Mercury, Johnson, and more) abounded. Retailers like Sears, Montgomery Ward, and Western Auto were all big sellers of boats and motors. The local Sears store of my youth included a boat department with several models on display, and a full selection of motors and accessories right in the department store. If you had a boat, you needed water skis, life jackets, and fishing equipment, too.

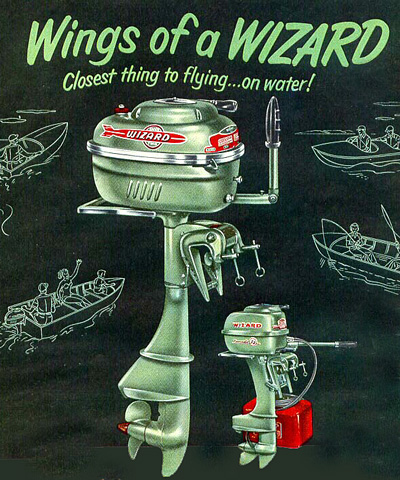

Wizard motors were sold throughout America at Western Auto Stores, a chain that once dominated the auto-parts business and was eventually owned by Sears. Western Auto was a large seller of boats, motors, and bicycles through the ’60s.

Reality Sets in

Ask almost any kid who spent time around lakes or oceans water skiing, fishing, and boating, and they’ll speak fondly of those times. Some of my best memories are of hours spent on my dad’s boat, watching as he so proudly skippered his craft, complete with captain’s hat and American flag flying from the mast. We would drop my mom off on shore and go out to the open water and crank up that Evinrude until the boat came out of the water and glided over the chop, my dad turning in circles so as to go back over our wake and splash water into our faces.

It may be the lens of youth, or it could be that life really did change for many Americans, but by the time I was old enough to start driving the boat myself, owning a boat didn’t seem like much fun anymore. Each year we would return to the same places and each time they had changed just enough to notice, or at least enough to disappoint my parents. The vacation cocktails came out earlier and earlier, and the boat stayed at the dock more and more as we kids fended for ourselves in the motel pool or on the beach.

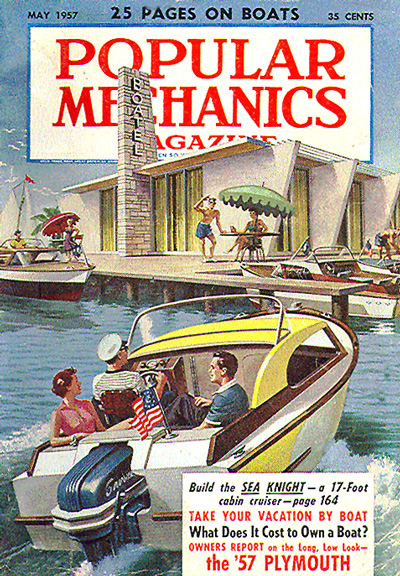

In 1957 Popular Mechanics pictured a time when “Boatels” would dot the shoreline as vacationers took to the water and left their cars behind.

By the time we went on our last vacation together as a family, the boat came to represent everything that could possibly go wrong. My dad was in a career crisis of some sort and complained of a headache the entire trip. We made the mistake of bringing our yipping poodle, Pierre, along, only to discover the motel where we stayed did not allow pets. My dad got a speeding ticket on the way to this vacation, and the motel put us in a small room my parents hated. My usual job of helping with the boat turned into helping with hiding the dog, going with my dad to the liquor store for supplies and Alka Seltzer, and listening to my parents complain. It was a sad way to end our relationship with my dad’s boat, but we never went on a vacation again.

Years later, my dad called and asked if I wanted his boat. It had been in storage at my grandmother’s house for ten years or so and he needed to find a new home. He was so proud of that boat that I knew I should have said yes, but I was living in an apartment and had no ability to deal with it, so I told him to sell it. What I have left are a bunch of boating magazines and the original plans he used to build it.

My dad’s home-built boat, which he never named. (It’s the smaller of the two!)

I sometimes regret not keeping that boat, if only for its symbolic value. I know the boats of today are much faster and more powerful, but from what I can see at the boat dealers I pass by, they all look pretty much the same, just like the cars of today. And just knowing how attitudes have changed, I have to bet there is a lot less hand waving on the lake or sea these days, or at least not the friendly kind I remember.

Read more by Gene Gable.

This article was last modified on May 19, 2023

This article was first published on July 7, 2005

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Animating Images With Plotagraph Pro

Plotagraph Pro is an innovative app that allows you to selectively animate still...

The Digital Art Studio: Illustrator’s New Crop Image Button

The 2017 release of Adobe Illustrator added a new feature you can use to permane...

10 Best Apps to Improve Your iPhone Photos

The cameras and processing power in today’s smartphones have come a long way sin...