Heavy Metal Madness: My Smokestack is Bigger than Your Smokestack

I always wanted to be a titan of industry — a big-shot mogul standing thoughtfully behind a huge mahogany desk, gazing through his picture window at the massive complex below. I’d feel powerful, meaningful, and satisfied, knowing that my products were changing people’s lives all over the country and the world. And that my workers looked up to me as a role model, provider, and tough but fair employer.

Figure 1: Titans of industry. In 1945 the Chase National Bank encouraged big business to send reconstruction goods overseas to help rebuild post-war Europe.

Figure 2: Important men making big decisions in 1935. Here, executives of the Walker-Turner Tool Company in Plainfield, New Jersey, discuss the fate of their sizable facilities.

Yes, a titan of industry back when the size of a smokestack said something about the size of the man. Billowing steam and smoke were the symbols of progress, not pollution. Sprawling factories were a brand’s prime asset, not a public-relations liability. The industrial revolution, after all, was making work easier, bringing all sorts of new manufactured goods to the world’s markets, and creating a massive number of new jobs.

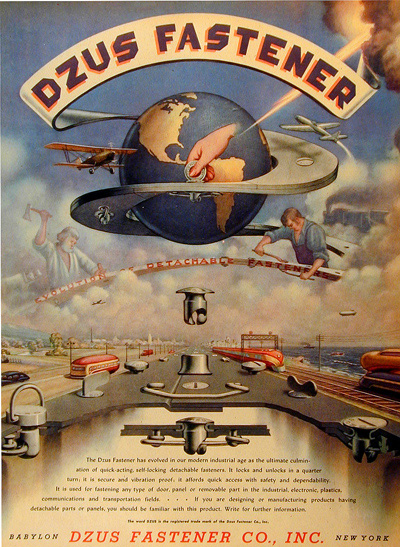

Figure 3: The Dzus Fastener Company, like so many others in 1946, was proud of the impact made by the evolution of their product, in this case the detachable fastener.

Figure 4: Gaylord Container Corporation still supplies boxes to American industry, but I doubt they’ve been using images like this one lately. If the smokestacks don’t get you, the cigarettes will.

For a while there, smokestack industries enjoyed an era in America where success was limited only by capacity and productivity. Resources were plentiful, labor cheap, and things like worker’s comp and class-action lawsuits hadn’t yet sent industry running to more desperate nations. The factory owned the town and called the shots. Cities fought over the rights to call themselves the “steel-mill capital of America,” or “home to the world’s largest paper mill.” We loved our industries — the bigger the better. So we showed them off wherever possible — on business cards, on matchbooks, in advertisements, on calendars and on postcards.

Figure 5: We’ve got the whole world, in our hands. Some companies are bigger than the whole world, actually, as shown here in a Forties-era ad for the Square D Company.

Figure 6: Men and machines as shown in a 1937 Commerce National Bank ad.

And it wasn’t just the buildings we liked to show off. Big-industry success was represented by illustrations of important men making important decisions, scientists discovering new breakthroughs, and contented workers doing their part by marching in each day and greasing the wheels of commerce. America came of age during the industrial revolution and proudly proclaimed “we mean business.”

Figure 7: It’s been a while since the Celanese Corporation of America has highlighted this gleaming Texas plant, where, according to the ad text, “modern chemistry is practiced on a grand scale.”

Getting Up a Good Head of Steam

It was Englishmen Thomas Newcomen, Thomas Savery, and John Calley who built the first working steam engine in 1712 to pump water out of a flooded mine shaft. Then in 1769, James Watt patented an even more practical steam engine design. From there all hell broke loose and before you know it there was steam and smoke pouring out of buildings all over Europe and North America. Man and machine were pictured working as one, together building a better future. Never mind any foul odors, toxic chemicals, or horrific industrial accidents. Nothing could stand in the way of progress.

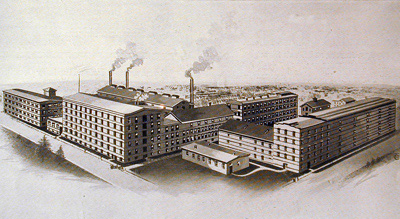

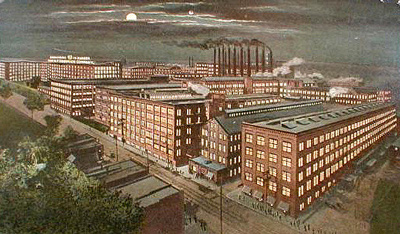

Figures 8, 9, 10: Turn-of-the-century businesses were very proud of their physical plants. Here the Leominster Shirt Company, The Chickering & Sons Piano Forte Manufacturing Company, and the Lancaster Mills in Clinton, Mass.

Steam-powered factories needed workers, so cities formed practically overnight, often without regard for urban or resource planning. Steam-powered railroads brought supplies, ships delivered exotic cargo, and men built manufacturing empires that forever changed the landscape. Steam power gave way to electric, or diesel, and the era of greenhouse emissions began.

Figures 11, 12: Two Scranton Pennsylvania firms from 1918, the Scranton Button Factory, and the Lackawanna Mills.

It took almost 100 years for folks to wake up to the down side of big industry, but we finally admitted all those visible and chemical signs of excess were not something to be proud of. The image of a billowing factory smokestack is now more likely to be used by an environmental group to demonstrate a point than by a company trying to create a positive community image.

Figure 13: At one time a company would not only admit it made varnish, but proudly show the plant billowing in the background.

Figure 14: The Manning, Bowman Company in Meriden Conn, made cocktail shakers, small appliances and other metal items.

Real Estate Matters, Sometimes

Corporate identity is rarely associated with a physical plant or building anymore, unless it’s some sort of charming historical reference, the business is a hotel, or the headquarters was designed by Frank Gehry. I still see quite a few small businesses promoting their location, though, and it’s a visual I’ve used several times in my own business identities. Displaying a physical location says “stability,” I think, and distinguishes you from a competitor across town in the strip mall, or across the world in some child-labor sweatshop.

Figure 15: If one plant is good, then five plants must be better. The Great Western Smelting and Refining Company thought so back in 1918.

Figure 16 and 17: Whether it was chocolate, as represented by the Hershey Factory (above), or paper from an International Paper Company plant, no one was shy about showing where their products were made.

These days when you flip through the channels or leaf the pages of Atlantic Monthly, the ads from Chevron, Dow Chemical, and U.S. Steel tend more towards tweeting birds and green forests than oil refineries, chemical plants, and steel mills. We have very few visual references for big-industry brands any more, which is something I’m sure the big brands are happy about. But I kind of miss the obligatory factory building artwork on the letterhead, standing proud and as a symbol of capitalism.

Figure 18: The Westland Rubber Band Company not only showed its factory, but the forests that were depleted to make its boxes.

Figure 19: You can bet the home of Chesterfields is no longer promoted quite so heavily as it was here in 1957.

Of course we’ve cleaned some industries up, moved past others, and shipped the most offensive ones overseas for someone else to worry about. The biggest building in most towns is no longer the “mill,” but the Ikea or Walmart store.

Figures 20, 21, and 22: For some reason big rubber companies were most proud of their manufacturing facilities. On these postcards the Firestone Company, Goodrich, and Morgan and Wright Tire Company all claim to have the “world’s largest rubber factory.”

No, it seems the era of factory art is over, and many of the big smokestacks in America have fallen way to more progressive businesses. Size and strength is measured entirely on stock price now, not on tonnage of effluent. And while I know this is better for all of us, I’d still give anything to lord over an empire where the blow of a powerful steam whistle signaled the end of the work day and let the town know it was time to break out the whisky and start dinner.

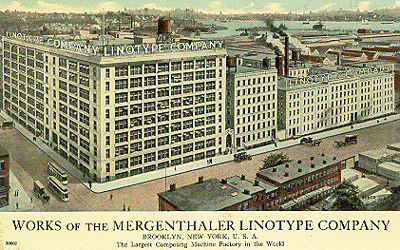

Figure 23: And just to bring things back to my column title, here’s the Mergenthaler Linotype Company’s Brooklyn facilities, long abandoned.

Read more by Gene Gable.

This article was last modified on May 19, 2023

This article was first published on February 26, 2004