Heavy Metal Madness: Keyboards I Have Known and Loved

If eyes are the windows to the human soul, then keyboards are the windows to the souls of machines. We focus on the screens because they are obvious and flashy and have the most to say. But just as we look into the eyes to tell us the truth that no amount of words can reveal, so I look to keyboards. There is only so much the machine can do if the material going in is flawed or forced in through a painful portal.

And if indeed what we do is called page “composition,” then we should demand good instruments between us and the pages we produce (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Even the Columbia Typewriter Manufacturing Company realized back in 1895, that composing a page of type is an artistic act, more akin to playing a symphony, and best done on a fine instrument.

So I have a tendency to judge most composition equipment on the quality, functionality and friendliness of the keyboard. Since I am temporarily on hold from any real mechanical progress in my letterpress print shop (while I await electrical work), I have been studying my latest keyboard challenge (on the Intertype), and contemplating the role that the layout, mechanics, height, sensitivity, and feel of it might have in my ability to compose letterforms efficiently, accurately, and with great pleasure (which is the only way to go, especially if it’s a hobby). Typing on a good keyboard is a delight few people experience anymore.

We’ve lost the art of typing almost entirely as a culture, thanks to the invention of computer memory. We typically no longer re-type information once it’s been keyboarded by the author. Reporters type in their own copy now, accountants put their own figures into spreadsheets, copy writers at ad agencies input their own words, even attorneys write their own briefs directly into Word. We’ve sped things up, made the world a lot more efficient, closed up the near-sweat-shop-like typing pools and composing rooms of yesteryear, and in doing so destroyed a craft and art that is much needed and overlooked. We are all manipulators of text, but few of us are really composers anymore.

Random Chance is the Mother of All Invention

Before Ottmar Mergenthaler invented the Linotype in 1886, there had been over 150 years of experimenting with devices that used keys to transfer human action into written words. Typewriter patents date back to 1713 or older, according to many sources, but nearly everyone ascribes the invention of the modern typewriter to Americans Christopher Sholes, Carlos Glidden, and Samuel Soule, in 1873. The three Milwaukee businessmen soon sold their patents to the Remington arms company, who went on to popularize the typewriter (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The Remington Standard is the direct descendant of the first typewriter built by Sholes and Glidden in 1873. They sold rights to the patent for $12,000.

It is a well-spread myth that the QWERTY layout we still use on keyboards today was designed by the inventors as a way to deliberately slow down typists by making it difficult to hit keys in rapid succession. This is not true. The specific layout of letters was meant to help speed by causing the least jamming of keys (based on likely letter combinations). Many competitive typewriter manufacturers used alternate layouts (see Figure 3), but none of them caught on like the Remington, and soon typing contests were being won over and over again by typists familiar with the QWERTY layout. In fact, it seems most early typewriter manufacturers never thought people would type with all ten fingers and not have to look at the keys. Touch typing as we know it, was clearly invented after the typewriter.

Figure 3: The Hammond Typewriter Company tried to promote an alternate keyboard to the QWERTY style popularized by Remington. It failed with that model, but after embracing the QWERTY standard, the Hamilton Company enjoyed moderate success and eventually became the Varityper company.

I’m not going to debate the wisdom of sticking with a QWERTY keyboard layout. There is quite a bit of information out there about the Dvorak keyboard layout, and other attempts at a better human/machine interface, but for some reason the QWERTY keyboard sticks with us today and I’m perfectly fine with it even if it is one big mistake that no longer makes sense for the devices of today. But being stuck with an illogical layout of keys doesn’t mean keyboards have to be the disposable commodities they have become (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Maybe it’s the cat hair, the coffee, or simply a heavy hand, but we burn through keyboards like light bulbs at our house. And even though you can’t fix them, I can’t seem to throw them out.

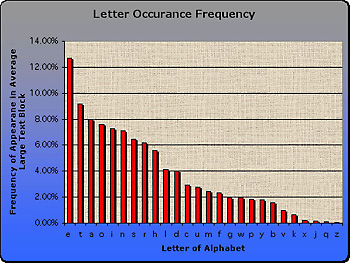

My new old Intertype machine has a completely mechanical keyboard — there are no electrical contacts, LED indicators, or membrane switches involved. When you press a key it causes a series of purely mechanical reactions (which is an important feature of a good keyboard — you need to feel that you are actually controlling something). And since there was no shift key on hot-metal composing machines, there are separate keys for both upper and lower case letters. Mergenthaler assumed he was doing the world a favor when he laid out the keys based on their frequency in the English language (ETAOIN SHRDLU, etc.) (see Figures 5 and 6). So even though Mergenthaler’s layout made better theoretical sense than the competing typewriter layout, it remained relegated to hot-metal composing machines and the mostly men who operated them. Typewriters, on the other hand, were promoted early as instruments for women — “easy, genteel, profitable,” according to Remington (see Figure 7).

Figure 5: The Intertype Model C has a keyboard layout very similar to the one designed by Ottmar Mergenthaler in 1886. The keys are arranged based on how frequently they appear in the English language.

Figure 6: Chart showing average frequency of characters appearing in several English-language novels.

Figure 7: Hot metal composing machines were almost exclusively operated by men. The typewriter, on the other hand, was marketed early as a tool for women workers.

Not only is the tactile feel of a keyboard important, but the design of a keyboard is too. Why are all keyboards designed with the main usage area offset to the left, so that it’s uncomfortable to use? Shouldn’t the number pad or arrow keys be on the left and keyboard in the middle?

Autodesk used to make a product called the “Switchboard” — a keyboard where you could rearrange the three sections. It was the best, alas they are not made any more.

Logitech’s diNovo keyboard is closer to nirvana, with a separate number pad that can be moved to the left. Really, how much do most users use the number pad?

Audio quality is also important. I recall an OS9 system extension that would make the sound of a manual typewriter when the keyboar was used. Perhaps that’s what is needed to bring back the feel of the “old days.”

Memory is long, but because I like Gene Gable’s writing I print off his articles for future perusal.

I thought I’d seen this article before and sure enough it first appeared on March 20, 2003, the fourth article in the then new series.

When you go the “Print Version” of the article the original date shows up but its “Web Version” has all the appearances of a new article, until you look for a date. New articles have current dates in the “Web Version” header this reprint didn’t have any date at all.

For some there might be nothing wrong with presenting old stuff as apparently new but I see it as a potential question of integrity.

Remember a number of years back, people were shattered when it was revealed that Ann Landers reprinted old letters without notifying her readers that they were reprints? The readers thought they were reading new material and felt betrayed when it was revealed to be old.

This isn’t the first time one of Mr. Gable’s article’s has been reprinted. (Or in the web world would the word “re-presented” be more accurate?) “The Creative Pro Next Door” didn’t stick in my mind as much as this article (I’ve been typing since Junior High in the 70’s) but I’d thought I’d seen it before. It’s only with the appearance of this second reprint that I checked.

There’s nothing wrong with Mr. Gable taking a vacation, or spending time getting his letterpresses up and running or being busy with projects like Context, meant to help the creative professional. There’s nothing wrong with identifying reprints when a new article isn’t available, and I do recall CreativePro.com identifying reprints of other authors’ work.

It’s only a little thing, maybe someone didn’t want visitors to be confused by the 2003 date or was too busy with the other work involved in getting the web site updated to reformat the “Web Version” header to include a statement about the article being a reprint. But little things can add up. Or maybe I’m being old fashioned, like an Underwood Typewriter.

how the heck do i get here if i leave and come back?

I designed a scanning keyboard for the Ultra Series machines. To avoid noise caused by vibrating reeds each key was integrated for 8 scans before detecting a “hit”. Even with an assembly language ISR the keyboard could outrun the Intel 8008 Microprocessor, so I also had a four-stage FIFO to hold keystrokes. I could also program any key to be a “Shift” key (i.e. state was maintained by hardware).

You could impact this Keyboard directly on the PCB with a Ballpeen hammer and not detect a single false keystroke. You could also mash down on the keyboard with both hands and apparently get every keystroke. I heard reports that some typists could achive 200 words per minute on my scanning keyboard.

I did that design in my 20’s now I’m in my 60’s and still doing hardware design at Key Technology in Walla Walla.

–TidyTim–