Heavy Metal Madness: It's All in the Cards

Like a perfect storm, several things happened recently that led to this particular column. First, an article appeared in the “Wall Street Journal” a few months ago about how Gen-Xers are taking up Canasta and other card games in droves, a desperate attempt to return to the simpler times when entertainment didn’t require memory chips or video screens. Then, the whole celebrity poker thing hit Bravo, complete with the cast of the West Wing bluffing their way to the big pot. And finally, I bought a box of over 1,000 playing cards at a garage sale that were collected in the ’40s and ’50s. So, being a victim of both pop culture and past culture, I had no choice but to do some research on playing cards, and explore the art involved therein.

One of the best things about buying someone else’s collection of something is that you find yourself owning things you’d never in a million years collect yourself. For instance, I ended up with over 30 different examples of Canasta card decks, from among the many wonderful cards included in my garage sale find. I paid $5 for a shoe-box size cache of cards that appear to have been collected by a young girl, based on the heavy representation of horses, ballerinas, and domestic pets. Some had notes on the back indicating where they came from and when they were acquired, or what they represented. And since there were only single cards in the box, I’m guessing kids often broke up their parent’s full decks and traded among themselves.

Figure 1: A garage sale find led to a collection of Canasta cards — something I never imagined existed, let alone had a desire to own.

Like so many popular past times, card playing created a special segment of printing companies, and helped drive the advancement of things like varnish-coatings, round-corner cutting, and lamination. But while the advancement of printing may have made card playing accessible to more people, card games clearly pre-date the invention of letterpress printing.

The World According to Hoyle

I started my playing-card journey by looking up Canasta in “The New Complete Hoyle“, an authoritative tome on the rules of play for nearly every table game there is. But I was disappointed to learn that Edmond Hoyle died in 1769 and wrote only a few short instructions on five popular games. Every “Hoyle” book since then is a rip-off, essentially, and Hoyle’s name is freely used by anyone wishing to sell books of game rules. There is, as it turns out, no “official” Hoyle book at all, and many of us grew up duped into thinking some family brain trust sits in a research facility somewhere documenting the international rules for everything from Three-Card Monte to Spit in the Ocean.

And though my confidence is shaken, I’ll take it on faith that Canasta indeed began in Uruguay just after World War II, then spread like wildfire to America in the late ’40s. By 1951, according to my faux-Hoyle source, Canasta was the most popular game in America. Canasta is Spanish for “basket” an assumed reference to the tray placed in the center of the table to hold discarded cards. There is no need for special Canasta card decks — the game is played by combining two standard 52-card decks. But the popularity of the game lead to the sort of special designs you see here.

Figure 2: Canasta was the hottest game in America in the early ’50s, and most of the card decks had a Spanish theme. Canasta means “basket” in Spanish.

Figure 3: Even more variations on the Canasta theme. Card design reached its peak in the Fifties, when card playing was still popular and advertising hadn’t completely taken over the industry.

Chinese Card Sharks

Once again we have the Chinese to thank for pioneering this art form, in part because they invented paper. Card playing is documented as early as the 10th century, though the Chinese version was more like paper dominoes, which were shuffled and dealt in various games. From early on cards were used to facilitate gambling and fortune telling, but I suspect the art of cheating pre-dates even the Chinese.

From China playing cards spread to the Islamic cultures, where cups and swords were added to represent various “suits” and “court” cards. By 1377 cards had arrived in Europe, and the court cards began showing kings, knights, and other royalty to represent higher values. Most cultures had their own suit symbols — it was the French who began the spade, heart, diamond, and club icons we know and love today. In the 1400s, decks were generally 56 cards — the court included a King, Queen, Knight and Valet.

Figure 4: The familiar diamond, club, spade, heart suit is from France. Other regions had their own symbols until modern times.

Figure 5: Card designs from the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt, around 1500.

The Germans, being the printers of the world that they are, produced many of the nicest cards, though until recent times Germans (along with the Swiss and the Italians) did not have Queens in their decks.

Figure 6: Art Nouveau playing cards printed in Altenburg Germany around 1900.

Figure 7: Lead letterpress playing-card printing plates from Germany as displayed in a recent eBay auction.

And of course it was the British who first put a tax on the sale of card decks in 1628 — there were a lot of wars to pay for. At one point every card had to carry a tax stamp, but later the stamp was only applied to the ace of spades, leading to the term “duty ace.” Playing cards were specifically mentioned in the British Stamp Act that so pissed off the colonists and led to the American Revolution. The taxation of playing cards was eliminated in 1960.

Like so many things before the invention of cheap, manufactured printing, playing cards were highly prized, hand-painted works of art often given as gifts at weddings or other formal occasions. Card decks were mentioned in wills, and it is unlikely that many Medieval children played 52-card pickup with those gilded beauties.

Figure 8: Latvian playing cards designed by Arturs Duburs in 1942. The Red Cross symbol was put on Latvian cards because the card tax went to fund Red Cross efforts.

Coming to America

But enough about other cultures. All that really matters is what happened in America, right?

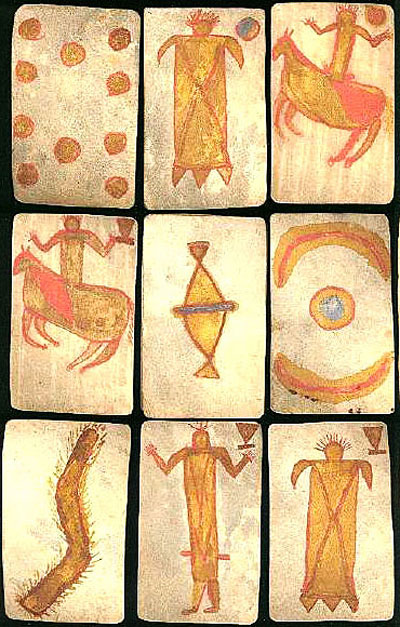

Figure 9: North American Indian playing cards, hand-drawn on leather, date unknown. Native American card decks generally consisted of 40 cards — enough to play the game “monte,” which was popular among several tribes.

Certainly early settlers brought cards with them from the old country, but it wasn’t until about 1800 that American printers began making card decks in good numbers. We can proudly take credit (according to at least one source) for being the first to make double-headed cards (no need to turn them over), round-corner cards (less dog ears), and varnished surfaces (easier to shuffle). And of course we were likely responsible for turning cards from works of art into advertising and promotional mediums.

Figure 10: In 1988 Adobe Systems commissioned a custom card deck as a promotion for Illustrator 88. Here are samples of the work of Paul Woods and Russell Brown. Group-designed card decks are still a popular artistic and political promotion tool.

Figure 11: These very odd images are from a series produced by the LF Dow Company.

Americans also invented the Joker card, around 1870, to represent the highest-value card in a game called Euchre, which I always thought was an exotic vegetable. Since this game was sometimes called “Juker,” the theory goes that the new card somehow morphed into being called a “Joker.” Sounds suspicious to me, but word-origin has always been a mystery. From the beginning, this card was represented by a jocular imp, jester, or clown, though the “wild” card nature of it allowed for almost any satirical image to be used.

Figure 12: The Joker has always been an interested visual. Here are several examples from the website Jokers Palace, a site dedicated to Joker collectors around the world (there seem to be many).

By the turn of the century there were many printers specializing in the production of card decks, leading to a wide variety of images and specialization. One of the most prominent was always the United States Playing Card Company, home of the popular “Bicycle” design known throughout the world. Started as an off-shoot of the Cincinnati Enquirer job-printing room, the firm was originally called Russell, Morgan & Company, then the United States Printing Company and finally, after specializing in playing cards only, the United States Playing Card Company. They then went on a buying spree, acquiring the second and third-largest card printers in the world, and a host of American companies.

Figure 13: The Russell Morgan Company became the United States Printing Company which became the United States Playing Card Company. Now the world’s largest playing card printer, they have been located in Cincinnati Ohio since 1867.

In order to promote bridge playing and the sales of more cards, the United State Playing Card Company started it own high-power radio station in 1922 to broadcast bridge lessons. During World War II, the company worked secretly with the US government in producing special card decks that were sent to American prisoners of war in Germany. When moistened, these cards peeled apart to reveal sections of maps indicating preferred escape routes. And during the Vietnam War, USPC produced special red Bicycle decks containing all ace of spades in order to aid in the “psychological warfare” against the Vietcong. The ace of spades represented death in French-Indo-China fortune telling, and US soldiers would spread the cards in the jungle and in villages in the hopes of spreading fear (you already know this if you’ve seen “Apocalypse Now“).

Figure 14: Playing cards played interesting roles in wars. Here, a plane-spotting deck helped citizens and soldiers identify war aircraft.

Still headquartered in Cincinnati, the United States Playing Card Company is the largest producer of playing cards in the world. One of their specialties is secure card printing for casinos — including “chain of custody delivery,” which monitors the cards at every shipping stage from the factory to the casino (to avoid any possible tampering). A museum at the headquarters (which is currently closed to the public) houses a large collection of playing cards and memorabilia, including cards dating back to the 15th century.

I still don’t know how to play Canasta, and I’ll probably never learn. But I sleep better at night knowing that some little girl’s Canasta card collection is safely in my hands, along with a shoe-box full of what I hope are happy memories.

Figure 15: These ’40s images of horses ballerinas and skaters were obviously popular based on the huge number of them in my garage-sale shoebox.

Read more by Gene Gable.

This article was last modified on May 19, 2023

This article was first published on May 20, 2004

Hi Gene, do you sell the cards you mention in your article “All in the Cards” ? I am very interested in the cards with ballerinas and girls with horses etc. please email me at blueroses54@yahoo.com if you are interested in selling any. regards Annie

One interesting development is the transition of playing cards into tarot cards (for fortune telling) OR tarot cards into playing cards depending on who you talk to. Tarot cards have their own rich variety of imagery and a variety of “systems” for using them.