Free Fonts Are a Myth

How many fonts do you own? The answer is probably “none.” Almost all fonts, whether bought or bundled, come to you with strings attached, and even ones that you’ve downloaded “for free” are in all likelihood only being licensed to you. You do not own them, you only own the privilege of using them, and they are—with rare exceptions—not yours to do with as you please.

Take, for example, the “free” fonts that come with your Windows or Mac operating system. They’re free only insofar as they’re not broken out as a separately priced item on your purchase invoice, but they are in fact part of that purchase. Both Apple and Microsoft consider these fonts to be part of the operating system. So apart from any rhetorical quibbling, you have indeed paid for them. Likewise, the “free” fonts that come with Adobe’s Creative Suite or Microsoft Office haven’t been given to you; they’re on loan under very strict conditions.

The bulk of these restrictions can be categorized as follows:

• which applications they can be used with

• on how many and which computers and printers a given font can be used

• whether you can embed a font in a document, and if so, how that embedded font information can be used

• whether you can use the font data as the basis for other fonts you might create

• whether the fonts you license can be used for commercial purposes

None of this information is hidden. It’s placed right under your nose when you install your software, even though you may not want to read it. Although reading the entire software license agreement may be lethal, the section on fonts is usually quite brief. Click here to read the section on fonts from the end-user license for Adobe’s Creative Suite 5—it’s only 400 words long.

In a typical end-user font license—for example, those of Adobe and Monotype—you are allowed to use a given font file on up to five computers linked to a single printer. Whether a font can be embedded, and whether a file using embedded fonts can be printed and/or edited, is up the maker of the font. Since the fonts bundled with applications and operating systems are often licensed from other sources, embedding restrictions may not be under the control of the people you’ve bought your application or OS software from. In almost all cases, you cannot use a font you’ve licensed as the basis of a new font you create.

When fonts are bundled with software—either an operating system or application—the general rule is that they can be used only with that software. What happens when you upgrade your software may seem to raise some confusions—you’re still an InDesign user no matter what version you use, right?—but your licensing agreement is quite clear: The fonts are bound to the version of the software they came with. When you bought Windows 98, for example, you licensed a set of core fonts for use with that operating system on the machine on which it was installed. Giving copies to someone using Windows 95 was forbidden, as was using copies of your Windows 98 fonts an old Windows 95 machine in your own office. Likewise, when you upgraded to Windows 2000, you were not allowed to use any Windows 98 fonts in Windows 2000 and vice versa. The same is true on the Mac, and your old System fonts should only be used with that system. Now that OS 9 System is no longer supported on the Mac, you can no longer legally use your old OS 9 fonts.

The same applies to Adobe’s Creative Suite, each version of which over the years has shipped with a different collection of “free” fonts bundled with it. According to the terms of their license with Adobe, Creative Suite users are not allowed to use, for example, their Creative Suite 3 fonts with the applications in Creative Suite 4. If these users have replaced CS3 on their computers with CS4, their license to use those CS3 fonts has lapsed altogether. For the Adobe legal department’s explicit explanation of this, click here.

In contrast, your end-user license for fonts that you’ve bought is open-ended and has no time limit. The fonts still aren’t yours, as the apartment you rent is never yours, but you do have a lifetime lease, unless you break its terms.

Free and Unbundled

There’s a second species of free font, of course: the ones you download without cost from the Internet. The temptation is to tar them all with the same brush: the admonition that “you get what you pay for.” But it’s more complicated than that.

Some free fonts are indeed second-rate (or third or fourth). They’re quick knock-offs. Yet others are sincere efforts of some quality, and their creators simply want to see them used by the public. Typical faults of these fonts are that they may not have all the characters you’d expect, and they may not profit from the hand of an experienced typeface designer or font maker. They may lack good kerning tables, for example, or competent character fitting. When you download a free font of this sort you shouldn’t be surprised by any of these shortcomings. Often these are available as shareware: The price you pay is voluntary, but even if you pay nothing, you’re still expected to obey the terms of the license under which you’ve obtained the font.

But there are many other free fonts available for free download that are of very high quality, and typically their cost-free access is simply a marketing gimmick. Such fonts are often licensed (not given away, note) on the basis that they’re used only for personal, non-commercial projects. This gives designers the ability to download a font, use it experimentally, and then decide whether to pay for a full commercial license for it. Unlike trial versions of applications, there’s no time limit on the use of such fonts, there’s simply a limit on how you can use them.

Always read the licensing information when downloading “free” fonts. It’s there somewhere. It’s a mistake to assume that free fonts come with no restrictions on their use. You have a responsibility to do the right thing by the person who designed that face and built that font.

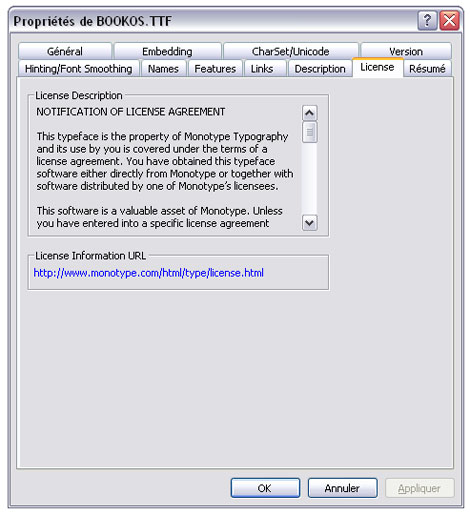

Furthermore, you should always know who that person or company is, no matter how a font came into your possession. To find this out on a Mac, open Font Book and choose Preview/Show Font Info to see who the copyright holder is for a selected font. If you’re in doubt about your license obligations for that font, contact the copyright holder or manufacturer. If you use Windows, go to Microsoft’s web site and download their Font Properties extension (Figure 1). This adds several tabs to the Properties window for all the OpenType and TrueType font files on your computer. With the extension installed, simply right-click on a font file and select the License tab to find out about that font’s licensing terms.

Microsoft’s Font Properties extension for Windows shows available licensing information for every OpenType and TrueType font on your computer. When such information is absent, there’s typically a link directing you to the font vendor’s website for detailed information.

The Font Properties extension is a great tool even if you don’t care about font licensing; it also displays a font’s OpenType layout features, notes the character set and encoding, and offers a brief history of the face’s design, among other things.

Respecting the People Behind the Fonts

Fonts seem to bring out the acquisitive in people. This is fine, as long as you respect the terms under which they’ve come to you. Even in the case of freeware fonts, it may be illegal for you to make a copy and give it to someone else. That’s certainly the case with fonts you’ve bought either individually or as art of a larger software package. Even the service bureau that outputs your files at high resolution has no right to use the fonts embedded in your documents unless they have their own separate license to use those same fonts.

Just remember that every time you make an illegal copy of a font, you just cheated a typeface designer somewhere out of a hard-earned royalty.

Hi Jim,

Your post provides an important and well-documented message. “Free” fonts almost never are. Type designers and font developers tend to come off sounding a little preachy when they tell the same story. It’s good to hear it from a typographer and graphic designer – especially one of your stature.

Thank you.

Allan Haley

Monotype Imaging

There may be one or two individuals on this planet that haven’t broken the rules of font licensing. A classic example is “up to five computers linked to a single printer”! How many offices have just one printer?! And how about a design studio with two inkjets, an office laser and a digital production machine or two? It is just simply not possible to stay within the guidelines so everyone breaks them left right and center. Now if they were a bit more realistic in the first place users might be more wary of stepping outside the license.

Interesting article. I don’t do a lot of font work so I never really thought of how that’s they’re creation and should be licensed or royalties paid. I’ve never run into this problem myself since I don’t do a lot of creative work but it’s definitely something that I wonder if everyone knows about. Most would never steal another artists’ drawings and place them in their work without proper licensing, but I wonder if they would do the same for fonts or free hosting for that matter.

Anyways, interesting article – but I’m sure they’re are royalty free, public domain fonts out there.

“It is just simply not possible to stay within the guidelines so everyone breaks them left right and center.”

And if you ask me, they’re justified in doing so ;)