Framed and Exposed: Zen and the Art of Aperture

Apple released Aperture, an image editor/workflow application aimed at professional digital photographers, in November 2005. At the time, most reviewers (including me) concluded that the program had some important, innovative new features but was hampered by performance issues, raw-conversion quality troubles, and bugs.

Within a month, Apple released an update that addressed some bugs and performance issues, and in late February, they announced another update that addresses the raw quality issues and several other common complaints. From the preliminary reports, it sounds like Apple has done an excellent job with this new update.

Even with these fixes, there are still the issues around Aperture’s use of an internal library. Many users and reviewers have complained that this library architecture makes Aperture inflexible when working with other apps in a more complicated workflow. I recently had an epiphany that made me believe those complaints aren’t just invalid, they’re born of ignorance.

We Didn’t Understand

I’ve been working on two books about Aperture (Apple Pro Training Series: Aperture and Real World Aperture and so have been using the program for almost all of my digital photography in the past three months. In the last few weeks, I’ve come to realize that few of us reviewers really understood some aspects of Aperture when we first evaluated it.

We’ve been approaching the program with preconceived ideas of how things should be done — ideas not just derived from Photoshop or any other editor, but from the general way we use computers. Aperture doesn’t fit into this mindset, and to really understand why it’s potentially such a good imaging product, you have to embrace some fundamental ideas about Aperture’s design. These concepts go all the way back to one of the original design philosophies of the Macintosh itself.

The Sound of One Hand Stacking

My Aperture awakening occurred while writing about Aperture’s stacking feature. Before we get to that epiphany, though, you need a little background on how Aperture works.

Aperture maintains its own internal library. Any image that you import into Aperture gets copied into this library. Those images are stored in the library as master images and are never altered. Instead, any time you make an edit, Aperture records the specifics of that edit in a small version document (an XML file) that’s stored alongside the master image. You can have as many of these versions as you want; when Aperture needs to output the image — whether to a display, printer, or file — it reads the pertinent list of edits and applies them to the master data.

Though this non-destructive approach is great, like many reviewers I complained vociferously about Apple’s proprietary library. The process of having to import and export your images into and out of Aperture’s library greatly complicates everyday document management.

Or so I thought.

Stacking is a unique Aperture feature that lets you group related images together within any particular project. (Images are kept within Projects inside the Aperture library.) Every stack has a Pick: the image from that group that you’ve selected as the keeper.

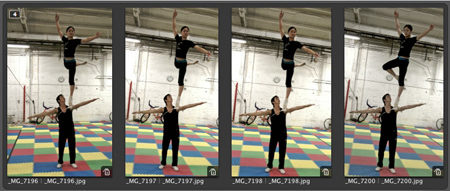

When a stack is closed, you only see the Pick, but when a stack is open, you can see all of its contents (Figure 1).

Figure 1. When a stack in Aperture is closed, you see

only the Pick image (top). When you open it, you see all of the other images that you have chosen to include in that stack. All images are completely editable.

Because most photographers tend to bracket their shots, or shoot in bursts, stacks are an extremely intuitive way to work, and Aperture provides excellent tools for building and managing stacks. Also, because Aperture is completely non-modal — you always have access to any tool — you can easily edit the pick, or any image inside the stack, at any time.

My stack breakthrough came when I was placing a stacked image into an Aperture Album. I dragged a pick into an album I’d created and, as it’s supposed to do, Aperture placed the entire stack into the album. This had always bugged me about Aperture because I didn’t see why I needed all of those other images in my album when I only wanted one. I could extract just the desired image and place that instead, but then I’d lose the advantage of my stack organization.

For some reason, as I was preparing to rip out just the image that I wanted, I got it. I’d been thinking of a stack as roughly akin to a folder in the Finder. So the idea of dragging an entire folder of extra documents into my album when I only wanted one image seemed silly. But a stack is not a folder. Yes, it can act as a container, but it can also act as a single image.

Say you’re working with an image and you decide that you need something a little different. If you’ve stacked your images, then you have lots of related images right there with that image you’re working with. Open the stack and you immediately see all the alternates. You don’t have to go out to the Finder and dig through folders to find other images that may or may not be grouped logically or have legible names.

My earlier mistake was to continue to think in terms of documents and document management. The idea of dragging an entire folder full of documents into a place where I only wanted one document seemed like a ludicrous duplication of assets. But I wasn’t copying an entire folder full of documents. I was placing the image I wanted where I wanted it, and if I output the album as a Web page, book, or other supported output form, only the Pick image would output. The rest of the images from the stack were available only in case I needed them.

Aperture was already doing all of the asset management necessary. It was only when I layered my own sense of asset management on top that things seemed convoluted and confusing.

This is the root attitude that keeps people from understanding how to use Aperture. Because Aperture was created with one of the original Macintosh design goals at its heart, we must give up a particular sense of control to get the most out of the program.

It Edits! It Prints! It Juliennes!

Apple marketed the original Macintosh as “the computer for the rest of us,” and one of the original guiding philosophies was that the Mac should act like an appliance. You couldn’t open it or add anything to it because it was an appliance — you wouldn’t add an extra heating element to your toaster, or an extra blade to your blender.

Aperture is a digital photography appliance. You put photos into it, and you get Web pages, books, prints, and/or edited files out of it. Along the way, you’re not supposed to care how it does what it does, or where it might store its assets. An application that’s less of an appliance, such as Photoshop, expects you to take care of a lot of the housekeeping work: managing and organizing files, keeping track of multiple versions, backing up, and so on.

When you bring these housekeeping habits with you into Aperture — habits you’ve developed not just from other image editors, but from most Mac programs — the program seems far less flexible and far more confining.

Right out of the box, Aperture provides an excellent import facility and good backup and archiving tools. These tools handle the bulk of your housekeeping chores. Many people are paranoid about the long-term implications of putting things in Aperture’s library, but it’s actually a very open system that lets you extract original images at any time, so there’s no need for extra archiving or backup tasks. If you want to back up your images, just tell Aperture to do it.

Of course, when it comes to image editing, Aperture is no match for Photoshop. Apple claims that Aperture provides 80% to 90% of the editing features most photographers need. I think this estimate is a little optimistic, but perhaps I make more selective edits than the majority of photographers.

Whatever the norm is, Aperture provides a simple way to move images into an external editor: Just select an image in Aperture and use the Open With External Editor command. Aperture automatically makes a new version of your image and sends that version to your image editor of choice. When you save from your image editor, that save automatically goes back into Aperture. (This feature had some issues with layered Photoshop documents, but it sounds like the 1.1 update addresses this problem.)

At first this may seem like an inefficient way of working because Aperture has to export a new version before you can start working in your external editor, resulting in another copy of your image. But in a “normal” workflow you would still at some point do a Save As of your new version, resulting in an additional copy. Aperture just makes this same copy at a different point of the workflow.

Once again, it’s only when you try to get in the way of Aperture’s housekeeping that the system breaks down. If, for example, you decide to save out multiple versions while you’re working in Photoshop, rather than letting Aperture handle your version control, then you’ll have a more complicated workflow than you would without Aperture because you’ll now have to manually import these new versions back into Aperture.

But if you think in terms of how Aperture functions, rather than in terms of how the Finder works, life will be much easier. For the time you’re working on images, Aperture replaces the Finder. Why would you want an application to do this? Because the Finder is a general-purpose document-management tool, and a digital photography workflow has special needs that a well-designed appliance application can better serve.

Why Aperture Is Like a Video Editor

Apple makes another application that hides media files in weird locations, forces you to use proprietary project formats, and allows you to extract media only via special export commands. That program is Final Cut Pro, and its users have good reasons for not complaining about these issues, despite two situations that seem frustrating from the outside:

- When you import a large movie into Final Cut, the program usually divides that movie into several different files (so no file exceeds 2GB) and stores each with a proprietary name somewhere deep inside your capture scratch folder. Therefore, to get a copy of your original capture, you have to ask Final Cut to make one for you — you can’t just drag it out of the capture folder.

- If you change the start or end point of a movie within Final Cut and then decide you want to take that movie into another program, you can’t copy that file out of your capture folder (even if you can find it). You have to render the file first to produce a shortened version. This is true for 99% of the effects and edits you can apply in Final Cut.

Video users put up with this lack of control because video files are huge and trying to manage them with the Finder isn’t practical. In this sense, Final Cut Pro is also an appliance. You put source video into it, you get finished video out, and you’re best off if you don’t worry about how the app manages to do this.

Video production pipelines, especially those that involve special effects, can be far more complicated than still-image production workflows because of the size of the media, color-space requirements, and the fact that you’re usually facing compression and re-compression concerns throughout the pipeline.

Smart video makers design their production pipelines to gang rendering tasks. With a little thought, you ensure that your time at the computer is spent performing interactive tasks, while your computational tasks are put off for rendering stages that can be performed while you’re away.

If you really pay attention the next time you’re working with a non-Aperture image editor, you’ll probably realize you spend many seconds here and there waiting for your computer. Waiting while images open; waiting while documents save; waiting while edits are applied. And you’ll probably find that you spend a fair amount of time navigating open and save dialog boxes, moving documents, creating folder hierarchies, and naming files.

With Aperture, things are a little different. Because Aperture essentially replaces the Finder, you’ll face a save dialog box when you choose to export an image, but when moving from one picture to another, you’ll never have to think about opening or saving, or performing any document management. And because of its real-time, non-destructive approach to editing, you’ll have long rendering wait times only when outputting final images.

In other words, Aperture’s approach to image editing is more akin to video editing, where you let your application handle all asset management, and all image-processing calculations occur at the back end during final output. While that output takes place, you’re free to do something else. Your actual time working at the computer should go faster because the application is handling a lot of housekeeping chores for you, and big computational tasks are delayed.

That doesn’t mean I now think Aperture is perfect in this or all other regards. The program is too sluggish on most machines, and there are too many rainbow cursors spinning around at inconvenient times. The program only supports RGB images, so you need to augment it with Photoshop for CMYK or LAB output when your workflow requires it. Also, because of its single library architecture, Aperture isn’t suitable for image cataloging. This is a serious problem Apple needs to address.

Most importantly, and Apple freely admits this, Photoshop is a far more powerful editor, for those times when you need powerful editing. But, if you think of Photoshop as a tool within your Aperture-controlled workflow and housekeeping, then interacting with Photoshop is not so complicated.

The More Things Change…

I’m not arguing that Aperture is the right program for you. I do want to point out that if you’re considering Aperture (or are using Aperture and are frustrated with its philosophy), then you should approach the program on its terms, not yours. Trust it and use the program in the way it was intended. Think of it as an appliance and let it do its job. Most importantly, stop thinking about the Finder and your normal document-management habits.

Of course, you may decide that that way of working isn’t for you.

When the Mac was first introduced, many experienced computer users couldn’t understand why you’d want a computer that didn’t expose its guts — both hardware and software. They couldn’t fathom that this loss of control wouldn’t affect what you were capable of doing with the machine.

With the OS X transition, many experienced Mac users expressed great remorse that they could no longer stick their files anywhere they wanted. They had to give up their freedom and follow the file structure dictates of Apple engineers.

In both of these cases, users eventually realized that giving up control and letting the computer do more for them was not only not a problem, but actually empowering.

Once you understand how to stay out of its way, you may well find that when you let Aperture handle the tedious housekeeping work computers are adept at, you’ll have more time for the photographic work that you bought an image editor for in the first place.

This article was last modified on January 18, 2023

This article was first published on March 6, 2006

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

CreativePro Tip of the Week: Make Illustrator Do the Math for You

This CreativePro Tip of the Week on making Illustrator do the math for you was s...

Heavy Metal Madness: A Woman's Work is Never Done

A few months ago at a rare family get together, when it came time for clearing t...

Adobe Introduces the Photoshop Photography Program

In a move that acknowledged the need for a cheaper, focused alternative to its e...