dot-font: Designing Running Heads

Learn the best practices for designing these inconspicuous but essential book page elements.

dot-font was a collection of short articles written by editor and typographer John D. Barry (the former editor and publisher of the typographic journal U&lc) for CreativePro. If you’d like to read more from this series, click here.

Eventually, John gathered a selection of these articles into two books, dot-font: Talking About Design and dot-font: Talking About Fonts, which are available free to download here. You can find more from John at his website, https://johndberry.com.

Sometimes the humblest and most inconspicuous elements of design turn out to be essential. A case in point in printed publications is the running head and its frequent sidekick, the page number. They may be humble, almost unnoticed, but if they’re done right they serve as signposts, telling you, the reader, where you are. The running head is part of the roadmap to any publication.

Most paper publications have page numbers, and a lot of them also have running heads (or running feet, if they’re at the bottom of the page). Sometimes the page number and the running head are in separate places on the page; sometimes they’re combined.

When you’re looking at a page of a larger document, whether it’s a book or a magazine or a business report, the running head tells you what publication this page is part of, and the page number tells you where you are in that publication. And in this day and age, when we often photocopy or scan a few pages for later use, the running head identifies what publication these pages came from, and who wrote them.

Running heads are purely navigational aids; they have no other function, and they’re not supposed to draw attention to themselves. But there’s a tendency for page designers, especially in books, to think of the running head as a chance for them to display their creativity. That’s almost always a mistake. Neither the running heads nor the page numbers should be decorative; they should simply be there when you need them, right where you expect them, and the rest of the time they should stay out of the way.

Where to Put It

The simplest way to format a running head is to make it a line of text, in the same size and typeface as the main text, but placed slightly above or below the text block on the page. It may be flush left or flush right or centered (never justified). The running head needs to be distinguished from the main text somehow (Figure 1), whether it’s by something as simple as using italics and adding a blank half-line or by something more active, such as adding a rule, changing the size, or even changing the typeface.

Figure 1. If it weren’t for the capital letters in “HADRIAN THE SEVENTH,” it would be too easy to mistake the running head for another line of text.

In a book of prose, sometimes the page number (folio) is separate from the running head; the running head, for instance, might be across the top of the page, while the folio appears at the bottom. But in many books, and most other publications, the page number is incorporated into the running head or running foot: one small block of type, with two or more kinds of information in it.

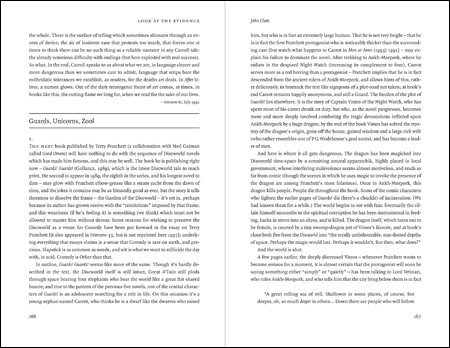

Usually, the page number is either centered or flush to the outside of the text block. We tend to look for the page number at the bottom outside corner of the page; if it’s not there, we look at the top outside corner. When the text block is justified, one common arrangement is to put the page number at the bottom, flush to the outside of the text block, and the running head at the top, flush to the inside edge (Figure 2). This way, if some of the running heads are long, they’ll still be unobtrusive, yet the page number will always be easy to find.

Figure 2. Page spread with running heads flush to the inside margin, page numbers (at the bottom) flush to the outside margin.

Another common way of handling these two elements is to keep them separate, but on the same line, either at the top of the page or (more rarely) at the bottom. The running head may be set flush to the inner margin, and the page number flush to the outer margin; sometimes, to tie them together, a thin rule may run under them, the full width of the text block (Figure 3).

Figure 3. On a complicated page, a rule under the running head can help to define the text area.

There’s a practical advantage to keeping both the running head and the page number at the top of the page. If the text may end at different points on different pages, or if you might need to add a line or cut a line at the bottom of the page to avoid a widow, then a running foot would draw attention to these variations; a running head would not.

How to Set the Type

What’s the best typographic treatment of the running head? Ordinary text type will almost certainly have ascenders and descenders, which are a great aid to reading in text but make the running head look visually busy. That’s why it’s so common to set a running head or running foot in small caps (Figure 4). If the text font includes true small caps, you can use them, suitably spaced, to make a very effective running head. (Be sure to letterspace the small caps slightly, so they don’t look clumped together, and be sure to use either old-style figures or specially designed small-caps figures, not full-height lining figures. I usually like the effect of old-style figures with small caps, but in a running head it might be subtler to use small-caps figures, if they exist in the font.)

Figure 4. Small caps with (top) old-style figures and (bottom) small-caps figures.

There’s a long tradition in book design, at least in books of solid prose, of putting the book’s title in the running head on the right-hand (recto) page, set in small caps, and the author’s name in the running head on the left-hand (verso) page, set in upper and lowercase italics. Usually this is done in running heads that include the page number.

On the other hand, when the text page itself isn’t symmetrical or justified, sometimes the running head simply aligns flush left with the main text block (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A guidebook to the Oregon Coast (left-hand running foot); this spread is in the section about the town of Astoria (right-hand running foot).

What to Include

What information belongs in the running head? It may be just a title or an author’s name, but sometimes it’s more complicated than that.

Even the page number can get complicated. Many technical documents, such as computer manuals, number their pages within each chapter or section, rather than continuously through the book: page 3-5, for instance, or A-15. This numbering scheme has no advantage for the reader, but it does make it easier for the people producing the book to deal with sections that are written out of order and may be completed at the last minute. Another complication might be to say “page 4 of 20,” although this is more common in electronic documents than in printed ones (Figure 6).

Figure 6. In a printed book, it’s easy to see how many pages remain; in a purely electronic document, it’s useful to specify the total as well as the current page number.

While running heads should be as simple as possible, there can be a good reason to include several kinds of information in the same running head. For instance, in a book with a lot of stories or essays by different people, it might be more important to see the title and author of a particular piece than the title or editor of the whole book. If those are all important items of information, you might divide them up, putting the book title and editor(s) on the left-hand page, and the story title and author on the right-hand page. You will almost invariably have to abbreviate: shortening a long title, listing authors only by last name, and so forth. But that’s OK; there’s no need for full titles or names in a running head, just the minimum information needed for identification (Figure 7).

Figure 7. You don’t necessarily need either a full title or a full author’s name in the running head.

Sometimes other kinds of information need to be included, such as the sponsoring organization or a reference to a related Web site (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Spread from Expectations, a magazine published by the Family Violence Prevention Fund, with enlarged images of the running feet below.

In reports, white papers, and many kinds of long business documents, it may be important to include a version number or date for the document itself. Sometimes there’s a requirement for copyright information or a nondisclosure notice; these can get out of hand quickly, forcing a running head or foot to grow large and unwieldy. Keep them as brief as possible; if they must be long, try setting them in a smaller type size, or using an unobtrusive condensed typeface rather than the regular text face. You may also be able to run part of the required verbiage on the left-hand page, part on the right-hand; however, this will work only if the document will be printed and bound in page spreads.

When you do have multiple elements in a running head, there are a few things you can do to separate them and distinguish them from each other, without making the running head look busy (Figure 9). Mixing small caps with italics could work—small caps for the title, say, with italics for the author’s name, if they have to be run into the same head. It’s common to separate items, such as page numbers from titles, with a centered dot (not a bullet, which is too big and bold). Another way might be the vertical slash (above the backslash on a standard American keyboard), though that depends on the typeface; sometimes it draws too much attention to itself. In either case, leave a small amount of space around the dot or slash.

Figure 9. Warren Chappell, the designer of this 1953 novel, used the two-page spread to communicate a number of different things in the running heads.

Suppose your book has extensive notes, and they’re collected at the end of the book rather than run as footnotes on each page. I’ve often seen academic books with page after page of endnotes, organized under subheads that simply say, “Notes to Chapter 7”; yet the running heads in Chapter 7 give only the chapter’s title, not its number. This is a failure of navigation; we don’t have the information we need to move back and forth efficiently between the endnotes and the text they refer to. One way to fix this is to include the chapter number in the running head; another is to add a page range to each of those subheads in the endnotes (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Detail from a page of endnotes in a book (The Golden Peaches of Samarkand) where the designer did remember to include the relevant page ranges (in both the subheads and the running heads to the endnotes). Ironically, the running heads in the chapters themselves do not include the chapter number, just the title; and the subheads in the endnotes do not include the chapter title, just the number.

In a reference book, such as an encyclopedia, the running head may change from page to page; it may include the current subject title, or a range of titles, or an alphabetical range. Most page-layout programs that generate this kind of running head automatically include only the first new topic title on the page, but for a reader leafing through the book, it’s even more useful to see the title of whatever topic is being continued from the page before.

Why

This is a lot about a very small subject, but the essence of typography is how you handle the details. Running heads are important tools for the reader; if they’re not done right, they fail in their purpose. If you’ve designed the running heads and the page numbers correctly, no one will consciously notice them, but they will serve their purpose.

This article was last modified on September 19, 2022

This article was first published on December 13, 2006