Super-Long Document Techniques with InDesign

A collection of recommendations and techniques for creating super-long documents with InDesign

This article appears in Issue 65 of InDesign Magazine.

What’s the longest document you’ve created in InDesign? Of course, I’m using the term “long document” to refer to the number of pages, not necessarily page dimension. Yes, a document 10 cm tall by 18 feet wide is pretty dang long, but it’s not the focus of this article! When I pose that “longest document” question to audiences, I often hear “24 pages”…“200 pages”…maybe more! I usually like to define “large document” as, say, 500 pages or more, but the truth is that when you’re on a deadline and the client asks for document-wide changes, even a 24-page booklet could be considered (and certainly feel like!) a large document when it’s not built properly. So the tips in this article are really relevant for multi-page documents of any length.

That said, I create a lot of long documents. I mean LARGE. Really large. Colossal, at times. A project I did last year was 20,000 pages…each copy filled ten bankers boxes (Figure 1). When you’re creating publications this long, you really have to pay attention to what you’re doing, or else you’ll jump out the window as soon as you have to change a color quickly, or adapt for more pages, or edit tables, or make any other kind of global change.

Figure 1. Now this is a long document. The boxes on the tables contain four copies of a 20,000 page proposal. On the floor, there are four more sets. Each “copy” of the document fills ten bankers boxes.

I’m not going to teach you how to use InDesign’s many features, but rather how to use them well. I encourage you to take the time to learn as many of InDesign’s features as possible before you tackle that 200-page catalog on a tight deadline. Because even the simplest task becomes a weekend-ruiner when you have to do it once per page…over 200+ pages.

Before You Launch InDesign

A successful long document actually begins before you ever launch InDesign. The best thing you can do is make a Plan. And an essential part of The Plan is to interview your client or boss and find out as much as you can about what they need for this project. For instance, knowing in advance they want a different dominant color for each section of a catalog can change the way you decide to build your document—you’ll probably want to break each section into a separate document. As you’re chatting with them, get a feel for how they think and work. If they are decisive and organized, you can make more permanent decisions than if they are flaky and disorganized. Saying things like “We’re not sure how many pages this will be…we’ll be adding and deleting and moving as we go” is very different than “We want a 208-page catalog and here is the breakdown for sections, common pages, and covers.”

Build Flexibility into Your Document

Regardless of which type of customer you’re dealing with, the more flexible the document, the more you can catch any curve balls they throw at you. To help maintain a flexible document, I offer a few rules:

- Avoid Multiples: Using multiple returns, spaces, and tabs is problematic when wanting to make global changes across a single document or across many. Don’t do it. If you want more space after something, edit the paragraph style or create a new style that has a larger Space After. If you find yourself pressing Tab Tab Tab…stop! Learn how to control tab stops so you can use just a single tab.

- Use the Fewest Frames Possible: If you are making separate boxes for your headlines and your body text, stop. Instead, learn about the Span Heads feature, and build this into your paragraph styles. This will eliminate the need to resize boxes as headlines are rewritten or you make style changes that increase or decrease headline size. Also, when making sidebars, if you are making a frame for the background and then another frame for the text, learn how to use Inset Spacing (Object > Text Frame Options) so you can make a single frame which contains everything.

- Think Before You Override Anything: If you are overriding a parent page item or a style, ask yourself: “Can I avoid this?” For example, a common mistake is to override a page number frame from the parent page so you can bring it in front of photos. Don’t. Instead, put the page numbers on a higher layer on the parent page so you’ll never have to override them. Or maybe you’re overriding the page number so you can change it to white when it’s over a dark photo. Don’t. You can create a second parent page based on the first one but with white numbers. Before you override a style of any type (paragraph, character, object, etc.), ask yourself: “Do I need a new style for this or is this really okay?” The fewer overrides in your document, the more flexible you’ll be when you need to make changes.

- Minimize Forced Line Breaks: Pressing Shift+Return/Enter is a common solution to forcing text onto the next line, but still keeping it in the same paragraph. I get it…I’ve done it myself. But try to minimize it. I saw a file recently where 90 percent of the forced line breaks could have been avoided just by turning off hyphenation in the paragraph styles. Similarly, forced line breaks can often be avoided with a simple change in the Indents and Spacing pane of the Paragraph Styles dialog box.

- Don’t Resize Frames…Change the Indents: As long as we’re talking about indents, learn how to use them to position text in frames vs. moving frames around. For example, if you have a catalog with a bunch of products all lined up, and the client requests that you move the copy under the photos to be more centered, don’t move or resize the frames: instead, indent the left side to move it over. That way, if the client changes his mind, you simply remove the indent and things are back the way they were. (I had this exact thing happen recently on a project, and all I had to do was clear the override on the style, and it was fixed on all of the spreads…in minutes instead of hours.)

Start with a Template

As I said earlier, I’m hoping you come into this with some InDesign knowledge. However, in case you’re new to InDesign, I want to point you in the right direction to get you started. First, build a template that will be your starter file for all documents you create for your project. This template file should include a few key ingredients. Note I wrote “file” as singular. You should have one file that is your template, and it should comprise all you need for all the documents you ultimately create for that project:

- Styles (Paragraph, Character, Object, Table, Cell and Table of Contents)

- Swatches you’ll be using, including an Adobe Swatch Exchange (.ase) file to be used with Photoshop and Illustrator

- Parent Pages

- Layers

- Preferences

You’ll want to have a template so complete that you can email that file to a collaborator and she’ll be able to open it and go to town on a section. And when she returns it to you for inclusion in the project, it will match the files you’ve been working on yourself. If there is anything in the list above that you haven’t mastered, I suggest you do some reading on how these functions can help you on this project. Each one of them is critical when it comes to long documents.

The Book

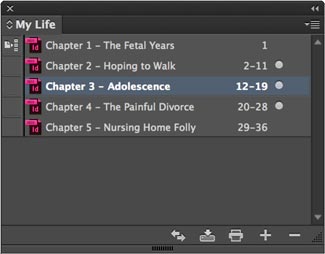

Different InDesign users have different thresholds at which they decide to break their project into multiple InDesign documents—some say if it’s over 50 pages you should split it, while others are comfortable with putting hundreds of pages in a single document. As I said earlier, sometimes the needs of the publication are such that you want to split it into smaller documents. But when you do split up your publication, use the Book feature (File > New > Book). This creates a panel where you can “load” all the InDesign documents in your project (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Book panel in InDesign

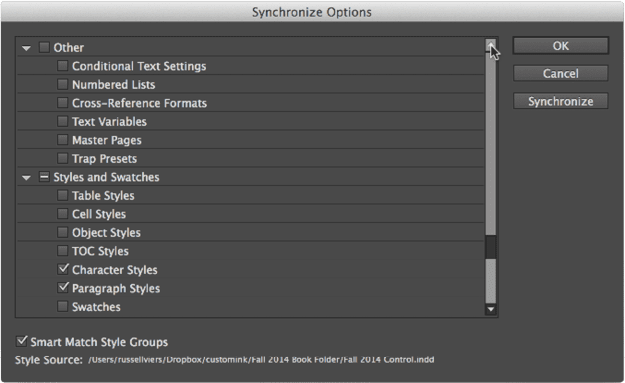

Figure 3. The Synchronize Options dialog box gives you a handy list of items to study and master in a long document workflow.

- Conditional Text Settings

- Numbered Lists

- Cross-reference Formats

- Text Variables

- Parent Pages

- Trap Presets (okay, you can skip this one)

- Table Styles

- Cell Styles

- Object Styles

- TOC Styles

- Character Styles

- Paragraph Styles

- Swatches

I can’t teach you how to use each of these in just one article, but I can give you some insight into how I think about them. I’ll start at the top and work through.

Conditional Text Settings

Often we have to make multiple versions of documents. A few years ago I worked on a 200-page document that had four versions. After talking with the authors, I realized only about ten percent of the book was going to change from version to version. I’m sure you’ve been in one of those situations where you have to make the same correction multiple times for each version because you made separate documents. Instead, we made one document, but with four conditional text states, which allowed us to toggle the various versions on and off. Correct once…all four fixed! But remember: punctuation is also included in conditions, so make sure you test as you go. You don’t want to be at deadline and have it not work. If done correctly, however, you’ll save hours of editing and proofing time.

Numbered Lists

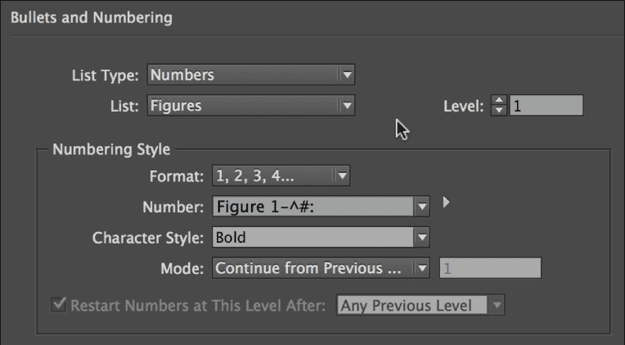

I love the numbered lists feature. On the surface, it might seem rather basic: “Yeah…I’ve done numbered lists…big deal.” But the numbered list feature is bigger than just numbered lists. Picture a 3000-page document that has graphics throughout, each of which requires a figure number. Most proposals, textbooks, and user manuals have this sort of thing. If you manually enter those numbers and try to keep them in order, you are killing yourself. What do you do when they add or delete a graphic on page 12? Do you go through and manually renumber? Stop it! Create a paragraph style for the figure captions with the numbering option turned on. Since you’re numbering from one frame to the next (and the frames probably aren’t threaded together), you will need to make a List. I name mine something clever like “Figures.” Then, as you apply that style to paragraphs, InDesign will look for the previous usage in the document, note the number, and add one. If you add or delete or move a graphic on page 23 (or wherever), all subsequent graphics, through the entire document, will update (Figure 4)!

Figure 4. A custom list allows you to continue figure numbering across separate text frames—and update the numbers quickly when figures are added, removed, or rearranged.

Cross Reference Formats

Let’s stick with that 3000-page document with Figures and Tables that we were just talking about, just for a bit longer. So now your customer says, “I want my authors to call out the figures in the body text, with the word Figure, the number, and the title of the graphic.” Again, manually managing this would be time-consuming and risky. Instead, you can make a cross-reference in the body that targets the paragraph style for the Figure and then pulls the text out automatically. So if either the number or the title changes, it will be an automatic fix once you update the cross-references. However, remember you’re not limited to the list of “Format” options available in the New Cross-Reference dialog box. You can make your own! If you do this, save it as a custom Cross Reference Format (or edit an existing one); then synchronize this across all the documents in your Book panel.

Text Variables

Text variables are like duct tape…so useful. Well, actually they’re not like duct tape at all. I mean, sure, they’re useful and flexible, but they’re not sticky or gray or on a roll or…well…it’s just a bad simile and I apologize. Editor, I think it’s better if you just delete this whole paragraph. The most common use for text variables is running headers and footers based on a paragraph style or character style on the page (Figure 5). You can have a chapter or section name automatically show up in your folio by using a text variable that references some text formatted with the appropriate paragraph style. There may even be times when you want the variable to reference text that doesn’t appear on a page anywhere. You can still use a text variable that looks for a paragraph style, but have the paragraph sit in a text frame mostly on the pasteboard, just barely touching the page. It’s a trick. It works.

Figure 5. The options for a Running Header text variable

- Go to the last page of the last document in the book.

- Somewhere on that page, put a text frame with at least one visible character (I just type “last page”), and apply a new paragraph style to it. Name the style something like “Last Page Number.”

- In the Attributes panel (Window > Output > Attributes), make the frame non-printing, so it won’t show up in your final document.

- On each of the parent pages where you want that “of XX,” insert a cross-reference to the Last Page Number paragraph style. That’s right: use a cross-reference instead of a variable!

This trick can be fragile, but it’s totally worth the maintenance, as it will update as you add and delete pages from each of the documents in the Book. Okay, back to variables. When it comes to looking at that Synchronize Options dialog box, I find that sometimes I want to sync my variables, and sometimes I really don’t. It depends on how I’m using variables: Plan A, Synchronize: Since you can synchronize text variables across all (or just the selected) documents in your book, you can create variables that will likely get changed later on—a publish date, for example. Your customer may think it will be published on a particular date, and that needs to be on all pages and in body text and other places, all formatted differently… but you’re pretty sure the date will change as time marches on. I like using a Custom Text variable for stuff like this because it can be changed everywhere in one document by choosing Type > Text Variables > Define. Then you can synchronize the book and all instances are changed in seconds. I just did this with a phone number on my last project—took me seconds to change four 40-page catalogs. Plan B, Don’t Sync: Now picture four catalogs for the same company, each using a different URL and phone number. You’ve planned ahead and created a text variable named URL and one named Phone, and synchronized them across all four documents using the book (so all the documents have the same variable name). But then you go into each document and change the definition of the two custom text variables to be unique in each catalog. So you used Synchronize to get the variable names “in sync,” but then you want to turn off the Text Variables checkbox in the Synchronize Options dialog box for the life of the project.

Parent Pages

Most people don’t realize that InDesign can synchronize parent pages across documents in a book, because that option is turned off by default in the Synchronize Options dialog box. But it can, and it’s awesome for making huge multi-document projects. But even if you know that you can do this with parent pages, there is one freaky thing InDesign does when you synchronize parent pages that you probably don’t know, and should know before you experience it and want to jump out the window. For this example, let’s say you’ve created ten parent pages, each with text and/or graphic frames to be used for various designs throughout your project. Maybe you’ve filled the graphic frames with gray so you can see where the pictures are going to go later, and maybe you’ve even filled the frames with placeholder text. (I don’t recommend using placeholder text because it’s too easy to forget to change it later and end up with lorem ipsum on press.) And let’s say you’ve used all these parent pages throughout your project, applying them to document pages, overriding the text and graphic frames as you need them, filling the frames with pictures and real text. Maybe you’ve even resized frames and moved them around on the page as you need. You’ve probably deleted a bunch that you ended up not using. But then you decide you need to change the page number or running header throughout the book, so you go to the parent page in one of the documents and update it. Then, you target that document as the “style source” in the Book panel, and you synchronize parent pages across the whole book. I hope you kept a backup before you synced, because when you look at your documents again, all of those overridden frames are back, just like your in-laws. That’s right: synchronizing parent pages duplicates all the objects that were overridden. It can be a disaster. You could go delete the items from those parent pages, and re-synchronize, but that’s pretty harsh—what if you need those parents again later? Instead, I like to create a new parent page that has nothing on it (but is based on a parent page that has the running heads and page number and stuff like that). Then I can apply that parent page to those document pages to strip away the “fpo” frames.

Table and Cell Styles

Just like the other kinds of styles in InDesign, table and cell styles allow you to apply formatting easily and consistently, and then change that formatting quickly when you need to. These styles become very powerful when they are applied to linked Excel spreadsheets. This workflow means other people can edit the spreadsheets up to the last minute in Excel and, as they save, you simply update in InDesign and the changes appear in the tables magically. Without table styles, you would constantly be reformatting the tables or, worse, placing new ones and reformatting every time there is a change. To link a spreadsheet, open the Preferences dialog box, click the File Handling pane, and enable “Create Links When Placing Text and Spreadsheet Files” (Figure 6). Now when you place an Excel file (or other formats, like Word documents), InDesign retains a link to the file on disk. If you apply your table style, any updates will still look as you planned.

Figure 6. When you know the data in a placed spreadsheet will change, select the option to create a live link to it.

Object Styles

Okay, this is an important one…maybe the most important for saving massive amounts of time: I apply an object style to everything! Many people only think of applying object styles when they want to change the look of a frame or path. But object styles can do much more than that. Remember that they can define and alter almost anything about a frame, including formatting text in a frame, insetting text, auto-sizing controls, fixed-width frames, columns and numbers of columns, vertical alignment, frame fitting options for photos, text wrap, and more. For example, I was just working on a 200-page document today, and under each photo I have a figure caption in its own frame. I created a paragraph style for each paragraph, of course, but also an object style named something clever, like “Figure Caption,” applied to each frame. I’ve defined that object style to apply the paragraph style, inset the text from the top of the frame, auto-size from the top, and apply a text wrap. So if my client asked me right now to drop the text further away from the graphic, or to put more distance between the caption and the body copy, I could do it globally in seconds without touching a single frame. I would simply change the options in the object style and synchronize that change to all the other documents in the book. Have you ever had frames fitting tightly against text that runs throughout your document, and then tried to make a change to the text using a paragraph style? And the text changed, as expected, but caused your text to be overset because the font was bigger? Had you applied an object style with Auto Size applied (perhaps Height Only from the top), the frame would have grown automatically to accommodate. Here’s another example: in this same project, I have applied an object style to every text frame on the parent page. That object style happens to be defined as a two-column text frame. That way, when my client wants to make the gutter wider, I only need to change the object style settings and I’m done. I hear you asking: “But if it’s on a parent page, why would you need to apply an object style? Why not go without an object style and just change the frame on the parent page?!” That might work. But what if I later copied and pasted one or more of those frames on the document page…then it would be divorced from the parent page, and that change wouldn’t follow through. As long as you use object styles, you’re safe to do almost anything in a document, knowing that later edits to the style will be honored. Seriously: the more you learn to use the awesome powers of object styles, the better off you will be.

Table of Contents (TOC) Styles

Not creating TOC Styles won’t kill you. Not using TOCs might, however. You just have to use InDesign’s Table of Contents (TOC) feature. I still encounter too many people who create long documents but who still manually create their own table of contents. Stop it! Learn how to make a TOC in InDesign. When working with long documents, don’t wait until the end to make your TOC. Since TOCs are created based on paragraph styles, if the style is not applied properly, the TOC won’t be correct. If you create a TOC at the beginning and make it part of the proofing process, you’ll be able to catch missed headings, etc., before it’s too late. For a TOC to work, you have to be vigilant in style usage. You could also use a script named StyLighter to audit all the overridden styles in your document and quickly find text that looks like Heading 1, but is really some other style just overridden to look like a heading. Also, if you are planning to use anchored objects tied to headings, you should know that those objects come with the text into the table of contents! If you want this, great. But if not, you might want to anchor the objects to the line below or above the heading instead. One last thing on TOCs: they aren’t just for making a table of contents. I’m often asked “How do I easily make an index?” Sure, InDesign has an index feature, but many times a TOC will actually work better because it pulls from a paragraph style that is already applied to text in your document, instead of having to go through and add all your index entries manually. This is especially true of catalogs where you might have every product name already formatted using a paragraph style. If you want an index of all of your products, just create a TOC that targets that style. Where TOC styles help you is when you have multiple TOCs used in the same document. For example, the catalog above needs a TOC for section headers, a different one for the product index, and your client wants you to quickly generate a list of SKUs and what pages they are on to verify that all the products are being used in the catalog as planned. You’ll have three TOC styles. Similarly, it’s common in nonfiction books and proposals for the customer to request a list of figures. This is a cinch to make when you have a paragraph style for your figures. Then, if they want a different one for the book’s tables, and you have a separate paragraph style for tables, it’s a walk in the park.

Paragraph and Character Styles

Everyone knows that you have to use paragraph and character styles in order to be efficient, right? Always. Always. Always. Don’t skimp. But here’s one “always” that not enough InDesign users know: Always have your paragraph styles based on either the Basic Paragraph style or some other “basic style.” (You can read the pros and cons of using the default Basic Paragraph Style that ships with InDesign in this blog post.) Of course, your styles could be based on some other style that is based on Basic Paragraph, or another style based on another style based on Basic Paragraph, or ano…you get the idea. In short…make all roads lead to whatever your base style is. Why use a base style? You can’t change the formatting of No Paragraph Style. But you can change Basic Paragraph, and this is going to be very useful should you ever want to make changes that affect all the styles. For example, let’s say you have 40 paragraph styles and they’re all based on No Paragraph Style (the default). When you’re almost done with your project, you find you want to make a change that will affect all those paragraph styles, like turning off hyphenation. Ouch. Had you based them all on a base style, you would need to make only one edit to that one style, and they all would have been changed. I use this technique the most when I push GREP styles out document wide, like if my client wants a certain company name italicized throughout. Simple: just add a GREP style to the base paragraph style, and all the others adjust automatically. When it comes to creating character styles, try to do as little as necessary. For example, if you want to create a Nested Style for a list, where the text is bold up to the colon, just make the character style be “Bold.” Don’t choose a font, size, leading, and so on, unless you really need for that style to behave that certain way. In my Character Styles panel, I often have styles named Blue, Bold, Bold Italics, Blue Bold, No Break, Superscript, and more. They each tend to be doing just one or two things. Unfortunately, this method doesn’t work if you are using fonts that don’t cooperate. For example, Museo Slab doesn’t know what “Bold” is. It only knows 100, 300, 500, and 700. So depending on the fonts you’re using, you may need one character style that applies “Bold” to fonts that recognize it, and one that applies “500” for Museo. This adds a level of complication I would rather not mess with when using GREP styles, so I try to avoid font families like this if I can.

Swatches

Synchronizing color swatches isn’t as slick as I would like—I want InDesign to read my mind and do what I want. But since it doesn’t, we have to trick it a bit. For one thing, let’s say you delete unwanted swatches from a document, and then set that document as your style source while synchronizing swatches across all the documents in the Book. InDesign won’t delete those same swatches from the other documents in the book. InDesign only adds and changes swatches when synchronizing; it won’t delete them. So if you have extra swatches, you’ll have to manually clean them up. Bummer. Also, if you name your swatches by CMYK values, which is the default, you may find yourself in trouble if you later change the CMYK values of a swatch. Changing the CMYK values may change the name, but InDesign isn’t smart enough to realize it’s the same swatch, and it will add it to all the other documents when you synchronize… and then you’ll have to go to each document and make it behave like you want. To deal with this naming problem, I do one of two things. First, if I want to ensure the colors update across all the documents no matter what I change them to, I’ll name my swatches something specific, like “Blatner Blue,” “Concepción Creme,” or maybe “Rankin Red”—or even just Color 1, Color 2, Color 3, and so on (Figure 7). This way, as you apply Blatner Blue to styles, frames, etc., and then change that swatch definition in one document, you can synchronize it across all the others, and Blatner Blue will chromatically modify everywhere it’s applied.

Figure 7. By naming swatches, you give yourself the ability to synchronize them across documents in a book. You can download this group of InDesign Magazine swatches at InDesignSecrets.

Adapt

In closing, just remember that even with the best-laid plan and best template, you’ll run into situations where you’ll need to adapt what you’re doing. That said, I can tell you that since my first 120-page catalog in 1987, using PageMaker 1, any time I cut corners and just used a quick fix, I ended up regretting it. So take the time to do it right. You have more time early in the project to prepare for the worst. At deadline, when everything is crazy, the last thing you need is to have your customer ask you to lighten the drop shadows from all the headers throughout your 500-page catalog and find that you forgot to apply an object style. Slow down. Be meticulous. Check. Double-check. Check again as you go. If you start out right, and keep things right as you go, global changes at the 11th hour will be a lot less stressful. Trust me…I’ve been there too many times.

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

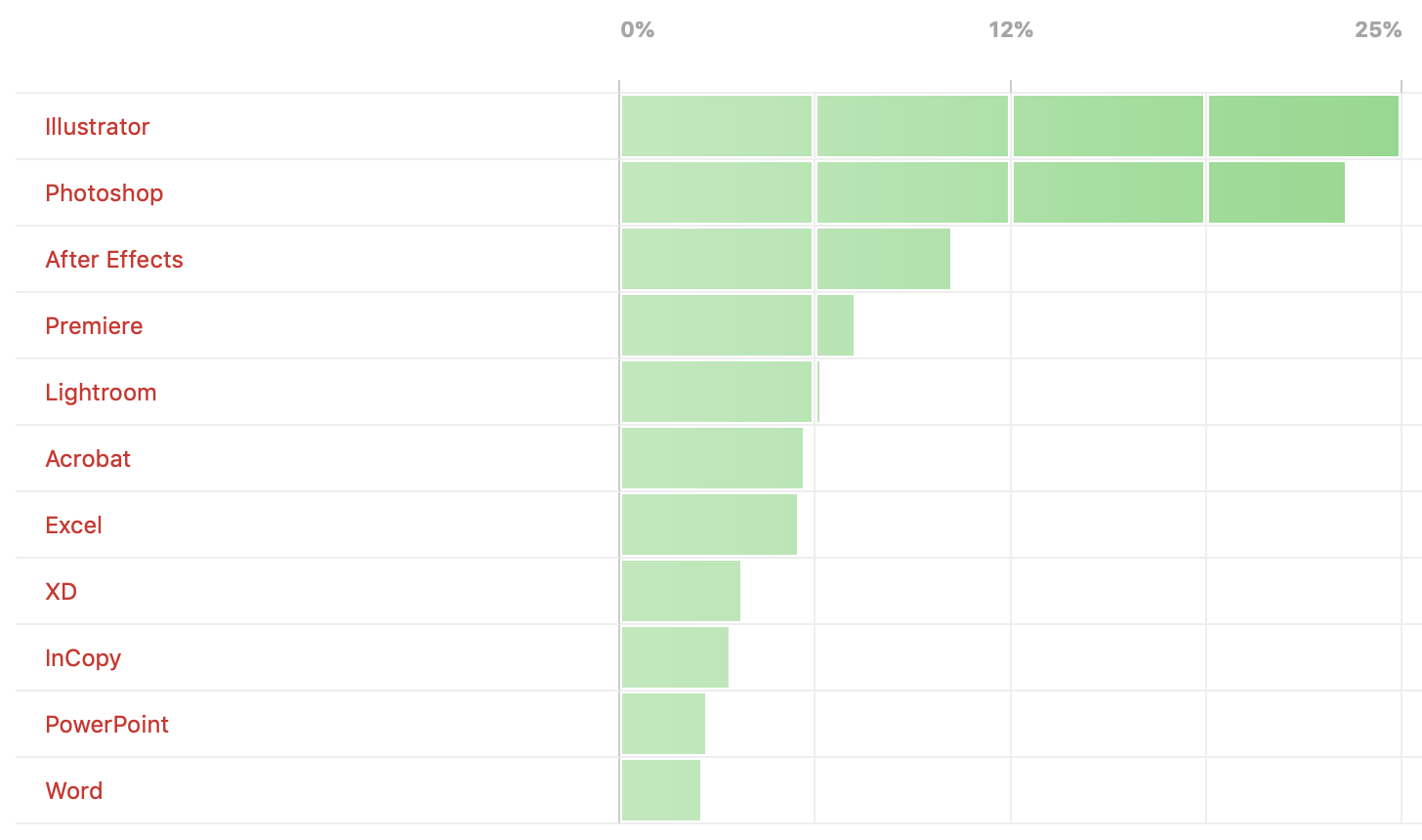

Poll Results: Which programs do you wish you knew better?

The results of our poll asking if you still use Flash (SWF) and a new poll on wh...

GoProof: The Modern Alternative to PDF Proofing

Every publishing workflow is only as strong as its weakest link. You can start w...

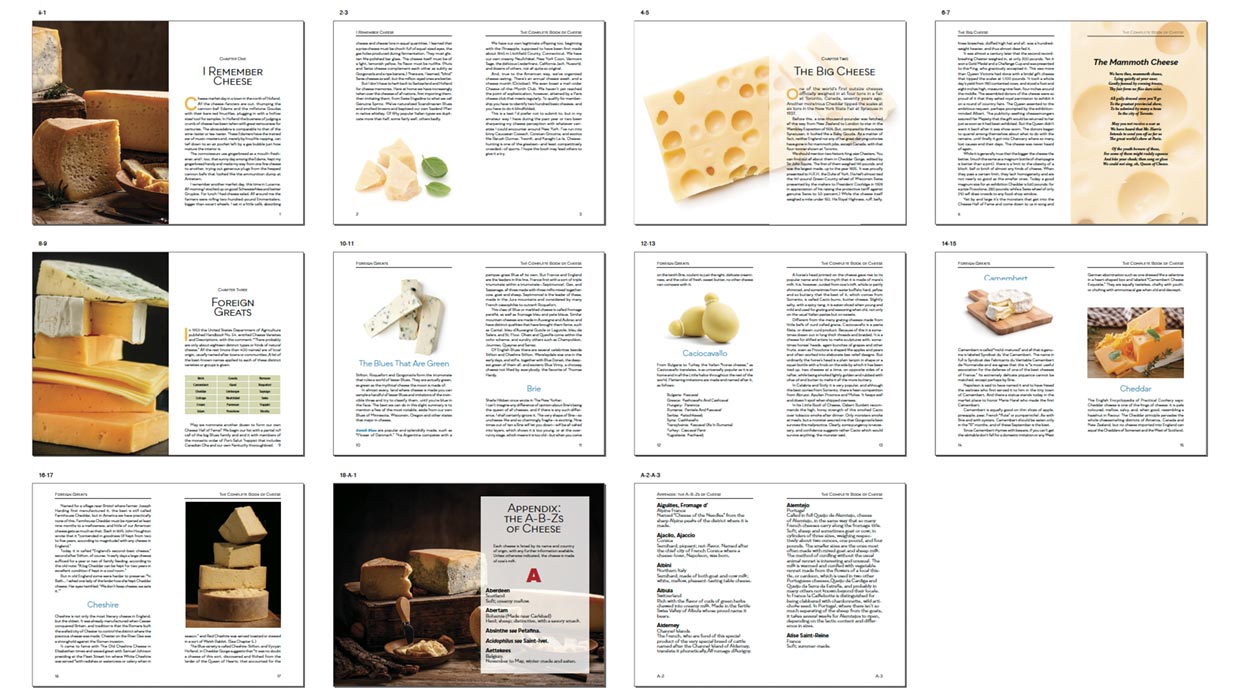

Creating a Flatplan in InDesign

How to use InDesign's Print function to create a file that you can then turn int...