You Can't Dance and Drive a Race Car at the Same Time…

When you think of writing and graphic design, you probably think of the two processes happening separately. In many creative workflows, designers and editors or writers briefly discuss general concepts at the beginning of a project — and then they won’t speak again until text is ready to pour into a relatively complete layout. Anyone who has collaborated across the Editorial Divide will be familiar with some problems that this way of working causes: layouts that don’t fit the provided text, or layouts that don’t suit the provided text, even layouts that have to be torn apart and rebuilt from the ground up in the wee hours of the morning. Even so, many one-person creative outfits work the same way: design first, and then write (or vice versa).

It doesn’t have to be this way. Design and text (and designers and writers) can not only coexist happily — from day one — in the same project, but also happen simultaneously. Jen Bilik, the creative director and self-described “head honcho” of the innovative design company Knock Knock, has a synergetic approach to the creative process — what she calls the “Whole Deal” method (Figure 1). She believes that writing and designing at the same time can enhance both aspects of a creation: “I think that you can come up with things in both the writing and the design that you wouldn’t get with either discipline alone.”

Figure 1. Founder Jen Bilik has channeled her love of writing and research, her droll sense of humor, and her passion for the entire printing process into intelligent, well-designed notepads, cards, office supplies, and gifts.

It’s an approach suited to projects in which text and graphics are well balanced and well integrated, such as Knock Knock’s clever and elegantly designed stationery and gift products. Bilik says, “You’re not going to write a novel while you’re designing, and you’re also not going to do a major Photoshop swirl and pattern while you’re writing. When you do both at the same time, you can’t have either one be too complex — the same way that you can’t do major ballet moves while driving a race car, but you can tap your toe while you’re driving in traffic.”

Figure 2. Knock Knock’s notepads balance textual and design elements in a streamlined layout, so they’re well suited to the “Whole Deal” approach to designing. To see a larger version, click on the image above.

A Structured Approach

For writers and designers working together, communication is of paramount importance — and not just about a piece’s high-concept aspects. It’s important to also discuss basic parameters. Bilik says, “It’s not necessarily the tone or the aesthetic. But how is the text going to be divided up into the design? And how is the design going to want to treat the text? So the writer and the designer each understand that their work is an ingredient going into a recipe, and they start to understand what the different needs are of each of the cooks.”

If you’re both the designer and the writer, the key to the “Whole Deal” process is structure: “Rather than writing or designing free-form, one must lay out the broad strokes of both, then the finer strokes of both, and so on.” (Many creative pros think that they “can’t write” — are you one of them? See “Writing Tips for Designers.”

Once you’ve got your concept, there are four basic steps in Bilik’s “Whole Deal” method.

Step One: Spew With many Knock Knock products, Bilik begins the creative process this way: “I sketch out the composition of the text and the layout in very broad strokes — without making font choices, without making color or pattern kinds of choices. Just so I can block out the text.” Then she “spews” — designing and writing without critiquing as she goes, and bringing her concept to life. At this stage, it’s important to focus on major design elements, not details. The writing should also be done in very broad strokes. Don’t worry about finding the perfect words or correcting grammar yet. Just let the ideas flow.

Step Two: Sculpt Saving plenty of alternative versions as she goes (so no potential masterpieces are lost), Bilik then takes a critical look at what she has so far, shaping the design, cutting unnecessary elements, and adding anything that seems to be missing. As her design begins to take shape, her writing does, too. At this stage, she works on refining hastily written ideas: “I think of this stage as sculpting because I am paring so much material away, or I am condensing lengthy ideas into brief, pithy statements.”

Step Three: Compose Now it’s time to impose some visual and syntactical order, and to polish your words. Bilik says, “You don’t want to waste time on carefully choosing words and sentence and paragraph structure when it’s material that you may not use. It’s analogous to waiting until you have an accepted design sketch before aligning and spacing and Photoshopping all the elements perfectly.”

Step Four: Finesse An important part of the final, minor-tinkering phase of a project is getting feedback. Bilik says that putting aside your ego is key: “View feedback as free ideas and advice that will save you from embarrassing yourself. If you don’t like a suggestion, take the fact that someone made a suggestion as an indication that what you were trying to do didn’t communicate, and try to make it more clear.” Ask people whose opinions you trust, and be specific about the kind of feedback you need.

The Wheel: An Idea Takes Shape

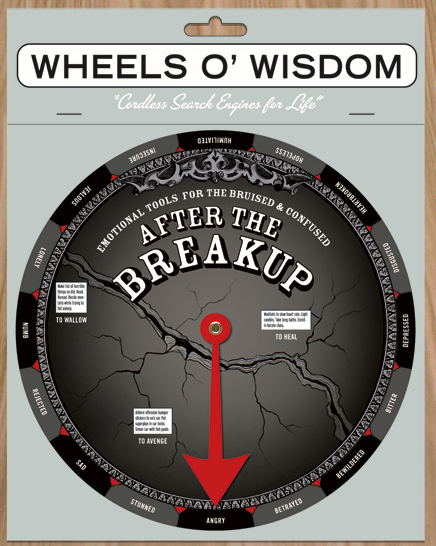

Knock Knock’s inventive Wheels o’ Wisdom paper wheels (or volvelles) were inspired in part by the vintage paper products and ephemera that Bilik loves: “Volvelles date back — I believe — as far as the 16th century. They were used in astronomy books. And we wanted their aesthetic to have a vintage feel as well. We explored circus-poster aesthetics, as well as Victorian snake-oil advertisements. The design of the wheels took Knock Knock designs in a different direction” (Figure 3).

Figure 3. For the Wheels o’ Wisdom, the typesetting is done in Illustrator, and the imagery on the top wheel is done in Photoshop and brought into Illustrator as an image. Jen Bilik describes herself as “an Illustrator girl, through and through” and credits Knock Knock’s art director, Trish Abbot, with cultivating the wheels’ shading, ghosting, and color in a way that really amplified the vintage feel.

For the first four Wheels, simultaneous writing and design helped the concept take shape. As Bilik worked on the design of the wheel, she wrote in an unlikely program: Excel. She says, “When you think about it, the wheel is a big spreadsheet. The left-hand column of a spreadsheet is parallel with the outer element. And the windows are like the top row.”

“And as it turns out, thank God I took geometry,” she adds. “When I did the first sketches of these wheels, I thought, ‘Oh, I’ll put the windows wherever I want,’ and I did some initial sketches where the designs incorporated the windows aesthetically. And then I realized that each window needed to be on its own orbit, and the text appeared in the window based on the intersection of a pie section and an orbit” (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The interior of the wheels is packed with text. When Jen Bilik did her first writing draft, she wrote as much text as she wanted. Then she realized that each capsule of text visible through a window at any given moment is actually quite short, and the closer you get to the center of the wheel, the more horizontal the text has to be. She describes the wheels as a balancing act between text and design. To see a larger version, click on the image above.

Bilik says that although she could have mapped this all out and then given a writer character counts for each window, dealing with character counts and word breaks was much easier because she was the project’s writer and designer: “Once I was able to get character counts, then I was able to go into Excel and write. So it was the experimentation with the form where the writing and design needed to go hand in hand.”

Figure 5. Knock Knock has released eight Wheels o’ Wisdom; four more are in the works.

Charles Purdy is a former managing editor of Macworld magazine and the author of the book Urban Etiquette (Wildcat Canyon Press, 2004).

This article was last modified on January 18, 2023

This article was first published on August 23, 2006

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

The CreativePro Guide to Graphics File Formats

Learn about graphics file formats, their pros and cons, and how to choose which...

Scanning Around With Gene: A Pre-Computer Lesson in Anatomy

I went to a new dentist the other day and was blown away by the technology they...

FAB Futures Award 2008 — and the Winner Is…

The winners of the internationally renowned creative awards program in the Food...