Using Google Fonts With InDesign

How to Find, Install, and Use Google Fonts in InDesign

This article appears in Issue 109 of InDesign Magazine.

If you’re a Creative Cloud member, you have access to Typekit, which at last count featured over 1500 type families for desktop use. But if, like me, you believe that you can never have enough fonts, Google Fonts is another large type library you can access… and it’s free!

The primary purpose of Google Fonts is to serve up fonts to websites. But, like Typekit, Google Fonts can be used for projects destined for print, PDF, or EPUB output as well.

Choices, Choices, Choices

Google Fonts is an interesting and often useful collection of over 800 fonts. The fonts cross a broad spectrum of categories and intended usage (see sidebar “Selections from Google Fonts”). Some are specifically designed to look great on small screens. Some are from independent designers and small obscure type foundries, while others are from more established firms such as ParaType, Production Type, and Dalton Maag.

Editor’s note: The heading font used by InDesign Magazine (Barlow Condensed) is a Google Font. You can learn more about our decision to use Barlow here. For more information, check out the article “Redesigning a Magazine” in Issue #106.

Selections from Google Fonts

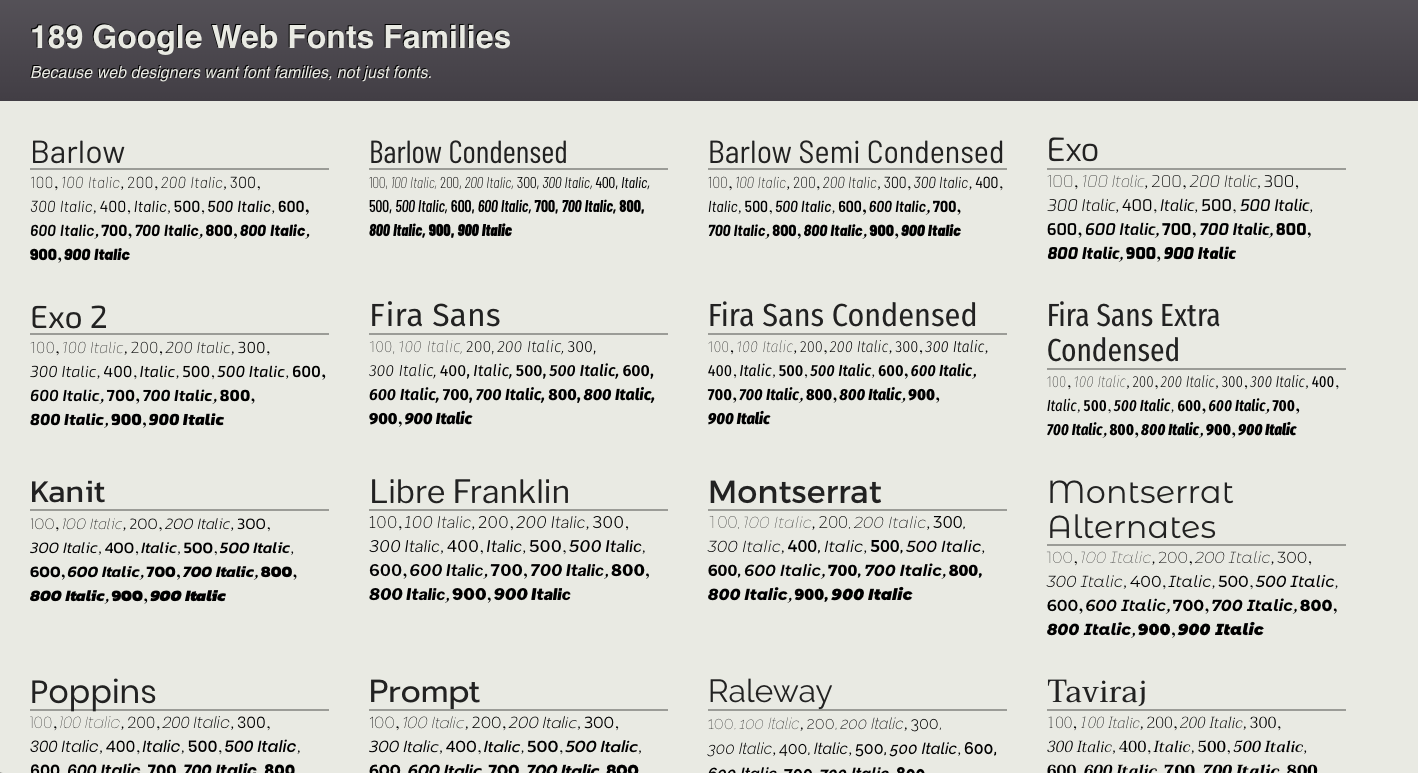

Google Fonts range from odd, unusual, and fun display faces…

…to quirky scripts and large families of body text faces.

You’ll find some overlap between the font selections at Google Fonts and Typekit. For example, all 18 weights of Raleway are in both collections, but Google Fonts features a “sister font” (Raleway Dots) that isn’t in the Typekit library. On the other hand, while Pacifico appears in both libraries, you get only a single weight in Google Fonts, and three weights in Typekit. And you’ll find PT Sans, PT Serif, and PT Mono are available on both services, but with Typekit, you can use them only for the Web. So it’s good to have access to both of these great resources.

Find the Perfect Google Font

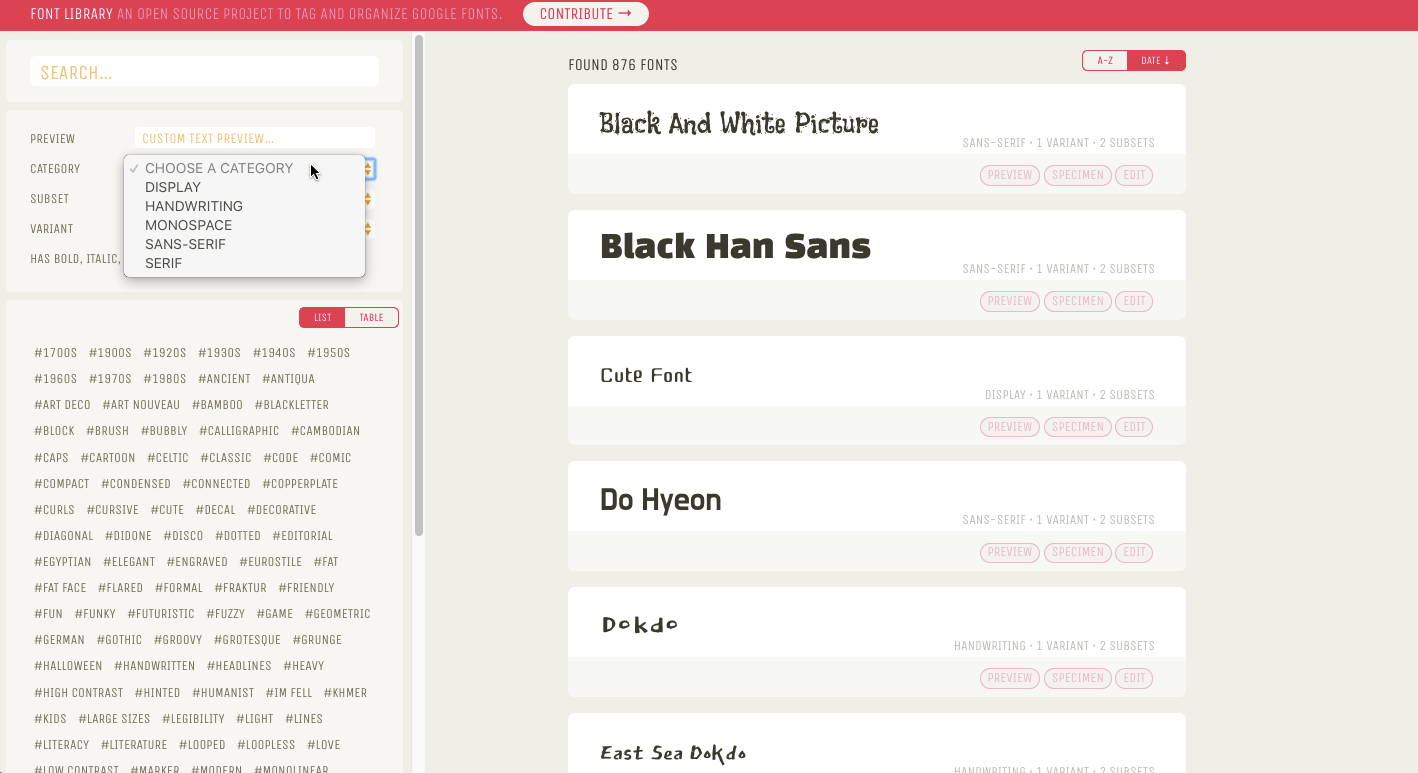

The more type choices you have, the likely it is you’ll spend hours trying to find the perfect fonts that project the perfect voice for your design masterpiece. Thankfully, Google Fonts has some unique features that can help. The sidebar on the right side of the Google Fonts Directory page lets you sort and filter the font list a number of ways (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The right-hand sidebar helps you filter and sort the list of Google Fonts. Here, I’ve requested serif fonts that use the Latin Extended character set that have ten or more styles in the family. This results in twelve listed fonts.

The directory listing itself can be customized to suit your needs (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Directory page at fonts.google.com can be customized to show a stock paragraph or sentence, or you can type your own sample text. You also can choose the type weight, and size, or click through to view a full specimen page.

Since the primary use of Google Fonts is to serve fonts to websites, Google has all kinds of analytics data on how often each font has been viewed on a website. You can see some of this data here. This data can give you a sense of how popular a typeface is for Web use. This popularity may or may not transfer to other usage of the font, however.

Google has made the Google Fonts API available to developers so they can create tools that let you “slice and dice” the font library in a variety of deep and geeky ways.

- Anatomy of Typefaces includes advanced filters that let you drag over histograms representing the attributes of Google Fonts to zero in on exactly the font you’re looking for.

- A Better Font Finder offers a unique (and fun!) set of controls for filtering the display of Google Fonts

- FontCDN gives you many options for viewing and choosing Google Fonts, including a nifty scrolling display of sample text.

- Font Library offers the ability to sort and display Google Fonts by category, language support, variant support, and date.

- Better Google Fonts allows you to browse typefaces that offer alternate glyphs.

If you prefer a type specimen book that you can print, ID Extras offers a PDF catalog that displays all the Google Fonts for $4.95 USD.

How to Get the Fonts

Once you’ve found a Google font you want to use, the simplest way to use it in InDesign is to download and install the free Skyfonts utility. This will sync Google Fonts to your computer, much like Typekit syncs fonts from the Typekit library. This same utility works with the Fonts.com, Linotype, Monotype, and MyFonts websites that all offer subscription access to their libraries, much like Typekit.

However, if you are already proficient at installing and managing large font libraries on your computer, and have a font manager such as Suitcase or FontExplorer installed, you’ll probably want to download the fonts to your hard drive and install them like any other font. In fact, with Suitcase Fusion you can enable a feature to automatically download and sync all of the current Google Fonts to your machine.

To download a single font or just a few fonts from Google Fonts, click the red plus sign next to the font you want. The font will be added to your list of selected fonts, and a black bar will appear at the bottom of the screen. Click this bar to reveal your list of selected fonts, and then click the download icon to download a single zip file containing all your selected fonts (Figure 3).

Fig 3. Here’s how to download fonts from Google Fonts to your computer. First, click the plus icon next to the fonts you want. Then click the black bar at the bottom of the screen. Finally, click the download icon.

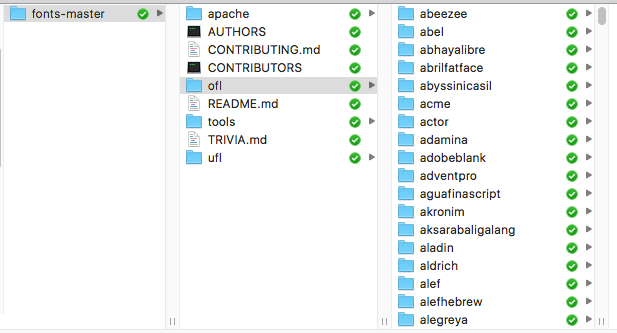

If you want to go nuts, you can also download the entire Google Fonts library in one download (Figure 4). Of course, the Google Fonts library is always growing, so you should still check out new releases in the future.

Figure 4: Visit here, and click the “Clone or download” button and then the “Download ZIP” button to download the entire Google Font library in a single download.

When you unzip the downloaded file, you’ll find the fonts organized into three subfolders (Figure 5).

Figure 5. When you download the entire Google Fonts library, each font family will be organized into its own folder. But the families will be spread across three separate folders, depending on the open source license used.

You can then install the fonts on your system using your font manager of choice. (I use FontExplorer Pro, but Extensis Suitcase or Insider Software’s FontAgentPro are also popular choices.) See Mike Rankin’s article, “Font Management,” in Issue #87 for an in-depth look at your options for wrangling fonts. I simply left the folder structure as is after unzipping, and dragged the entire top-level folder into FontExplorer to create a font set (Figure 6).

Figure 6: The Google Fonts font set as it appears after I installed it as a FontExplorer font set.

Google fonts vs. Typekit fonts

Google Fonts

- Google Fonts

- Over 800 fonts for desktop use

- Completely free

- Open source

- Font files visible on your system so they can be backed up, converted to other formats, etc.

- A mix of TrueType and OpenType formats

- Classified into 5 categories (serif, sans serif, display, handwriting, monospace)

- Can be copied when using the Package command

Typekit Fonts

- Over 1500 fonts for desktop use

- Creative Cloud membership or other payment plan required

- Some restrictions on use

- Font files hidden by your operating system so you can’t (easily) get at them

- All fonts in OpenType format

- Classified into 8 categories (serif, sans serif, slab serif, script, blackletter, mono, hand, decorative)

- Not copied when using the Package command

OpenType Features

All the Google Fonts filenames have the .TTF extension, so you might assume that they are TrueType fonts. Actually, most of the large type families and the newest fonts are saved in the OpenType or TrueType format. OpenType fonts use either PostScript or TrueType technology to draw the shapes of the glyphs. OpenType fonts based on PostScript have the .OTF extension, those based on TrueType have the .TTF extension. You can determine whether a font is TrueType or OpenType by looking at the icon displayed to the right of the font in InDesign’s font list (Figure 7).

Figure 7: The “O” icon in InDesign’s font list indicates an OpenType font, while a “TT” icon indicates a TrueType font.

Regardless of format, all of the fonts work seamlessly across Macintosh and Windows computers, and can be embedded in PDF and EPUB files. As you might expect, many of the OpenType fonts contain advanced features such as support for fractions, alternate swash characters, additional ligatures, and more, but the TrueType fonts don’t.

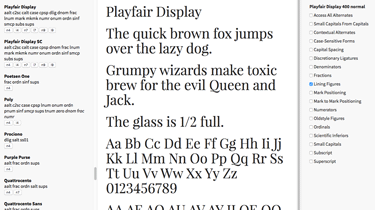

Unfortunately, on the Google Fonts web page there doesn’t seem to be a way to view which advanced OpenType features are supported by which font. Suppose you’re looking for a serif typeface that supports both oldstyle and lining numerals as well as true fractions. I’m happy to report that the interactive tool here can help with this (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Visit here to explore the OpenType features of various Google Fonts. Click on one of the rectangles below a font on the left side (each rectangle is a specific font weight and style), and a list of supported OpenType features appears on the right along with a font sample.

Font Licensing

All of the fonts in the Google Fonts library are free and open source, so the license (included in the folder with each font) specifically states that you can use, change, and distribute these fonts to anyone and for any purpose. Most fonts use either the SIL Open Font License (OFL) or the Apache License, while a few use the Ubuntu Font License. You can see a detailed list of the copyright and font license info for each and every font in the Google Fonts library here.

And a Font for Every Season…

Fonts reflect a voice or an intention. Sticking with your tried-and-true font choices is fine, but by expanding your font options you also expand your ability to fine-tune your message and express yourself. It’s worth taking some time to explore this enormous new cache of free fonts that type designers have made available through Google.

This article was last modified on November 10, 2025

This article was first published on May 3, 2018

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

TypeTalk: Justified Text

TypeTalk is a regular blog on typography. Post your questions and comments by cl...

19 Top Combos of the 19 Top Typefaces

Anne-Marie Concepcion spotted the interesting post “19 top fonts in 19 top...

Fonts on Friday: Food Fonts

What better time to round up new typefaces than on Friday. Not only is “Fo...