The Quarkification of Adobe?

When Adobe Systems announced last week that it was charging $99 to registered users to upgrade to InDesign 1.5, I wasn’t the only publisher whose jaw dropped. What? The nerve. Who do they think they are, Quark?

Yes, Adobe Systems surely seems like it’s pretty big for its britches these days, reminding me more and more of the company we all love to hate from Denver, Colorado. Quark’s customer service has long been legendary for its ability to frustrate customers. In the last year, however, the company has made a great effort to change that image (do you have your own story about working with Quark? Use the Vox Box at the top of this story to tell us).

Adobe’s stock price has been climbing steadily since late 1998-following Quark’s failed attempt at a hostile takeover-and the company has been recording record revenue for three quarters in a row now, including $282.2 million in the first quarter of 2000, ended last week, or 24% year over year growth.

Don’t get me wrong. I love Adobe. There’s a reason that so many of their technologies and products are the de facto standard in today’s publishing environments. PostScript revolutionized prepress production, and there’s not a graphic designer today who doesn’t use Photoshop on a daily or even hourly basis. The company makes robust, workhorse technologies that interact as seamlessly as any products do, and I know that I, for one, wouldn’t be where I am today without them (the fact is they’re a current client, and I co-authored a book published by Adobe Press, so their money is definitely in my pocket).

Now Adobe has it too!

But I’m puzzled. Adobe’s technologies are often introduced to the market after other companies have pioneered equivalent features in other products. Take layers. They were introduced in Photoshop 3.0 after FITS Imaging’s Live Picture and Micrografx’s Picture Publisher both had layers and multiple undos. And Adobe Acrobat was initially designed to offer portable documents for cross-platform business communications. Only after prepress professionals saw the potential for its clean PostScript, editability, and page-independent workflow did Adobe finally accommodate their needs with Acrobat 4.0 last year. (And if you may recall, Adobe initially charged for the Acrobat Reader, which can now be downloaded free on the Net. According to Adobe, there are 120 million Reader users-and that number is growing by 100,000 downloads a day-making it one of the most popular software applications in the world).

And now the big push, the big opportunity, is Web design and imaging software. If you read Adobe’s press releases and news stories about Adobe’s record earnings in the last few quarters, you’ll find that everybody likes to attribute the company’s incredible growth to the Web. (A Reuters news story last week even tried to tie Adobe’s increased Acrobat sales to the release of Stephen King’s e-book, “Riding the Bullet,” which can be read as a PDF-don’t get me started.) There’s some truth to that: what’s selling are Photoshop and Acrobat, but both of these are used in print as well as online publishing. According to a recent market study that I saw, very few Web designers are using ImageReady, the-I must say, excellent-Web imaging product that comes bundled with Photoshop 5.5. Adobe’s $999 (list) Web Collection is popular, but folks are buying it for Photoshop and Illustrator, not for GoLive.

Which brings me to the dirty family secret that no one likes to talk about: Adobe’s two graphical Web layout programs-GoLive and PageMill-are pitiful sellers, faring much worse in the market than competiting products: Macromedia Dreamweaver and Microsoft FrontPage, respectively.

How do they do it?

But what’s even more amazing is that Adobe didn’t even release any new products last quarter, and according to many dealers and resellers that I’ve talked to, InDesign sales are much slower than expectations, especially considering all the Quark-killer hype that surrounded the product’s release last summer. (Dealers also complain that Adobe isn’t providing enough training and marketing resources, hampering their ability to sell InDesign.) The page-layout program’s slow acceptance shouldn’t be too surprising, really, given that publishers must be careful when introducing new software into a production workflow, and most probably wanted to wait at least for InDesign 1.5, if not a later version, so that bugs get fixed and the product is even more fully integrated with PDF and capable of “round-tripping,” which is Adobe’s new buzzword.

The company’s test of customer loyalty last week backfired, but to its credit, it retracted and announced that the upgrade would be free-and therein lies the secret to Adobe’s success. Sure it’s a big corporation, bogged down by its own bureaucracy and always striving to increase profits, but it also truly wants to serve its customers. (I’m not sure the same can be said for Quark.) The result is that Adobe products do what designers need done, with the features that they really need both to unleash their creativity and to be productive. And even if their products are a little late to market, it’s worth the wait because you know the interface will be familiar and the products will integrate well. More important, you’ll be able to achieve efficiencies that you couldn’t before, and the software will take you in directions you didn’t even know you needed to go.

During this second quarter, word is that Adobe will be making several significant product releases. The one I’m waiting for is an upgrade to GoLive, but I won’t hold my breath. Given the company’s recent history, however, I’m awed to imagine how a quarter marked by aggressive product releases and upgrades will drive up its revenues and stock price.

Anita Dennis is a freelance writer and editor who has covered electronic publishing, including Web design and digital printing and prepress, since 1993. Her work has appeared in numerous industry magazines, including Publish, i/o, Red Herring, and TrendWatch and she is the co-author of Web Design Essentials (Adobe Press, 2000).

This article was last modified on March 10, 2025

This article was first published on March 22, 2000

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Book Review: Pencil: Do More Art

A clear and concise guide to exploring the wider world of graphite possibilities...

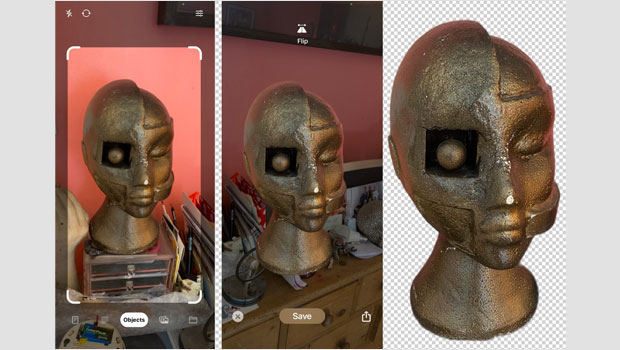

Capture and Cut Out Images on the go with Scan Thing

Get to know an iOS app that makes silhouetting images a cinch

Before&After: Design a Showroom-Style Presentation

This auto magazine feature layout is a fair illusion of walking page by page thr...