Scanning Around with Gene: The Joke's on You

Before Hollywood brats got “Punk’d,” and before political opponents hacked each other’s Web sites, the art of the practical joke was a bit simpler. You might be offered a stick of gum, only to have your finger snapped, or maybe you would freshen up at a neighbor’s house and exit the bathroom in black face, the victim of novelty soap. Or, if you were particularly vulnerable, you could count on something exploding in your face or sparking a sneezing fit.

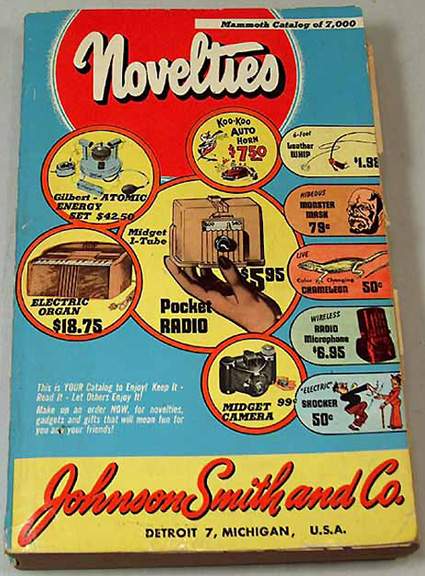

I was recently reminded of these and more than 7,000 other novelties as I pored through a 600-page, 1940 catalog from Johnson Smith & Co., purveyors of novelty items since 1914. The company, which is now headquartered in Florida, still sells such quality gags as farting monkeys, dog-doo candles, and hillbilly teeth, only now they have six different catalogs, each tailored to a unique demographic. One of the very early American mail-order companies, Johnson Smith & Co. has always specialized in “memorable gifts that delight, entertain, and amuse.”

My own exposure to the practical joke came very early in life. My dad was a bit of a jokester, and it wasn’t unusual for him to emerge from his workshop having made some small wooden device meant to torment and embarrass his children. And dinner conversation all too often (from my mother’s perspective) turned to stories of boyhood adventures tormenting neighbors with remote-control door-bell ringers, potatoes inserted into car tailpipes, and smoke bombs rigged to starter motors so on ignition they bellowed as if the car was on fire.

We kids didn’t take up my father’s passion, but we did often visit the downtown magic shop to pick up some sort of inexpensive gag item like fake vomit or gum that tasted like garlic. Sadly, every kid in town was familiar with these items, so it was rare to actually fool anyone other than some unsuspecting great aunt or child on a tricycle. I remember one such attempt with my grandmother that turned into a feeble effort to explain why it was funny to call her a “lettuce head.”

A Unique Form of Humor

The practical joke has always had a somewhat dark side. The “victim” is intentionally made to look foolish, causing embarrassment and indignation. In this case the term “practical” refers to someone doing something that would normally be a natural act (opening the door, accepting a stick of gum, starting the car). This is opposed to a “verbal” joke, which uses only words to convey humor. “Slapstick” (physical events with unpredictable outcome) is different, as are “pranks,” which are deliberate, outrageous acts, such as balancing a car on a bell tower or filling a room with balloons. Johnson Smith & Co. sells products that fit in all of those categories.

It’s a bit hard to trace the history of the practical joke. More than likely, humans have felt pleasure from cruelly embarrassing one another ever since jealousy reared its ugly head (probably when we still had scales). Plus, we all love to get a laugh, even if it’s at another’s expense. Sometimes, especially if it is.

But many scholars tie the birth of the practical joke to April Fools Day, which emerged around 1852 in France. At that time, Charles IX reformed the calendar and moved New Year’s Day from April 1 to January 1. Since Al Gore hadn’t invented the Internet yet, news traveled at a much lower bandwidth, sometimes taking years to get out to the masses.

Citizens who continued to celebrate April 1 as the beginning of the new year were thought to be “fools” by those in-the-know. Accordingly, these folks began to be sent on “fools errands” and otherwise humiliated. Fake party invitations were sent out, stories were made up, and the gullible were tested to see just how foolish they might be. And through one of those unexplainable cultural improbabilities, paper fish were often hooked on the fool’s backside, thus indicating that, like a foolish fish that is easily caught, these victims were so stupid they would walk around all day with an undiscovered fish on their backs. This hilarious buffoonery eventually lead to the more contemporary “kick me” sign, thought to be popularized by the Scots (see below).

One time when I was by myself in London during Christmas, I was standing in a queue at the local market when a very hip young Brit behind me took something off my back and handed it to me. It was a Post-It note that said “I’m Gay” on it. We all acted very correct and nobody, thankfully, was laughing as far as I could tell. But I was mostly looking at the floor and frantically trying to find correct change for my purchase of American Fig Newtons and some Walkers short bread. Something like that really does make you feel foolish, regardless of the sentiment expressed.

As the practice spread throughout the world, the specifics changed from country to country. In Scotland, for example, April 1 is called Taily Day, in reference to the practice of buttocks-related practical jokes. (No, I can’t cite any examples, but this area of the body has always been a favorite for joking.) In England, the victim of a practical joke is called a “noodle,” and it’s thought to be bad luck to play any practical jokes after noon. And my favorite is Rome, Italy, where the holiday is known as Festival of Hilaria. They also celebrate Roman Laughing Day on March 25, so it is now official in my mind: Italians are the funniest people in the world.

Of course, April 1 is just an extra incentive to do what comes naturally to many people. The practical joke is a form of entertainment and, unless particularly sadistic, in good fun. Ideally, the victim of a practical joke quickly gets over the embarrassment and becomes part of the laughter. (Until, that is, they gracefully excuse themselves to the bathroom and either weep like a baby or rip towel dispensers off the wall and shove them down the toilet.)

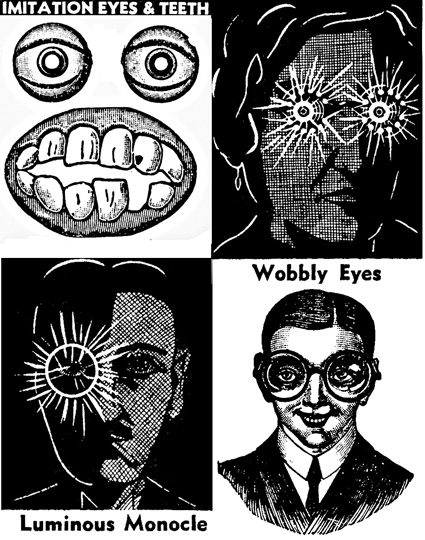

Innocent hilarity is certainly the spirit of the Johnson Smith & Co. However, when the above images appeared in 1940, the practical joke was more likely to cause pain or involve potentially harmful explosions. But that was more a sign of the times than the indication of a mean spirit. I’m sure the same gags today carry extensive warning labels, and the gunpowder has been replaced with audio chips and small speakers. Through trial and error (and costly lawsuits), we’ve discovered that even the classic Whoopee Cushion can be harmful when swallowed by a two-year old, inflated in a pet’s mouth, or placed in such a manner as to cause some poor senior citizen to fall off a chair and break a hip.

Some Gags Stand the Test of Time

It’s interesting to compare the current Johnson Smith & Co. Web catalogs with those of the past. Quite a few items from my 1940 version have changed very little, still causing red faces and peals of laughter more than 60 years later. Of course as expected, something that once cost 12 cents is now 12 dollars. And even though it still seems to be a very friendly company, you won’t find this kind of copy in a current catalog: “Remittance may be sent in any form most convenient to yourself. Just please yourself. It is immaterial to us how you send your money as long as it is in some cashable form. You can remit by money order, bank draft, currency, coin or postage stamps.”

According to Wikipedia, practical jokes fall into a number of categories. Since I agree with most of that entry, I’m re-capping a selection of those categories here, with my own spin.

False Signaling

These are jokes that take advantage of our willingness to accept certain things on faith. So when we put an “automatic door” sign on a normal door, we can be sure someone will bash into it. Similarly, if we carry a large box and act like it’s heavy, when we drop it on the victim’s foot, we can predict they might freak out for at least a few seconds. In the Johnson & Smith & Co. catalog, many items fall into this category, such as rubber dumbbells, fake rodents, arrows-through-the-head, and a rubber hand that detaches when someone shakes it.

Surprise Disruption

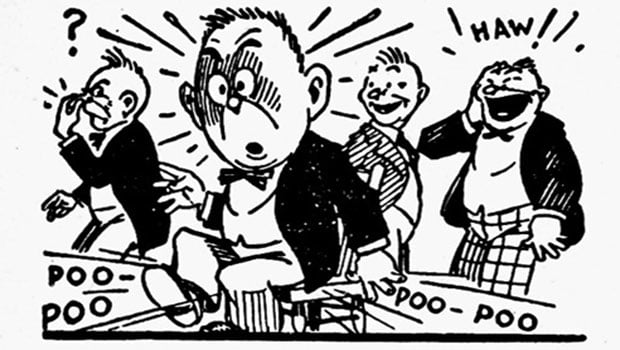

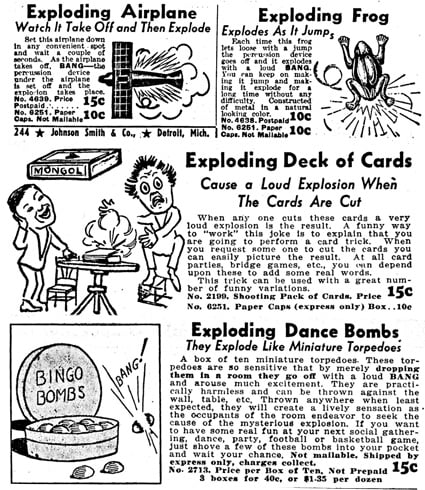

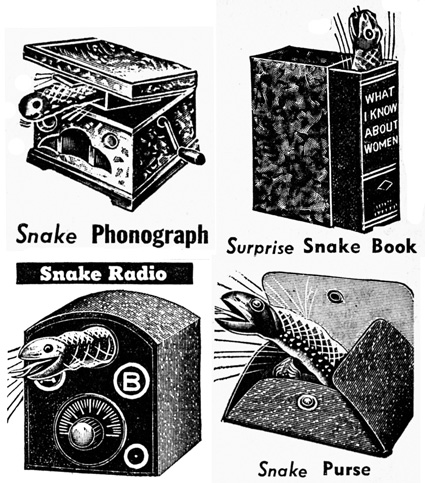

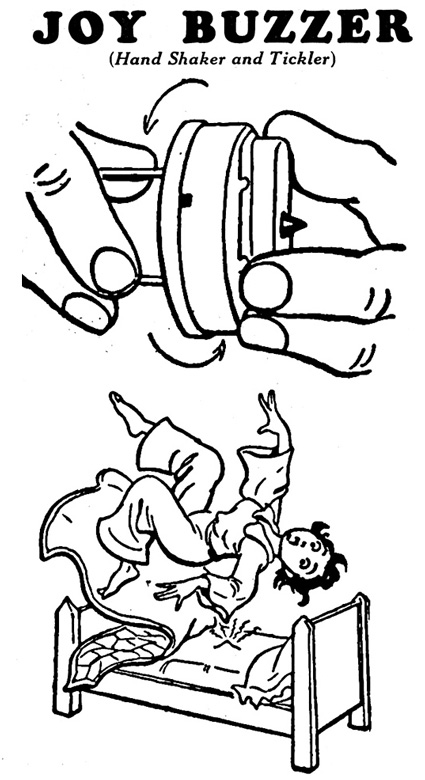

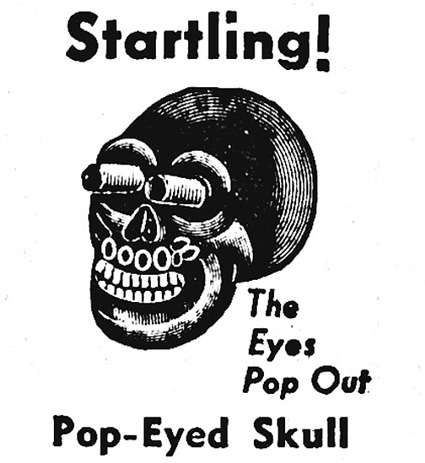

Exploding matchbooks, whoopee cushions, golf balls that pulverize when hit, and doorbells that sound like car horns are examples of surprise disruption. A normal act has a shocking (literally, sometimes) result. The artwork showing these items is most amusing, with exaggerated facial contortions, high jumps, and body convulsions used to show surprise. Novelty art is a genre all its own, I think-part science fiction and part cartoon. That novelty companies advertised heavily in comic books should be no surprise.

Visual Deception

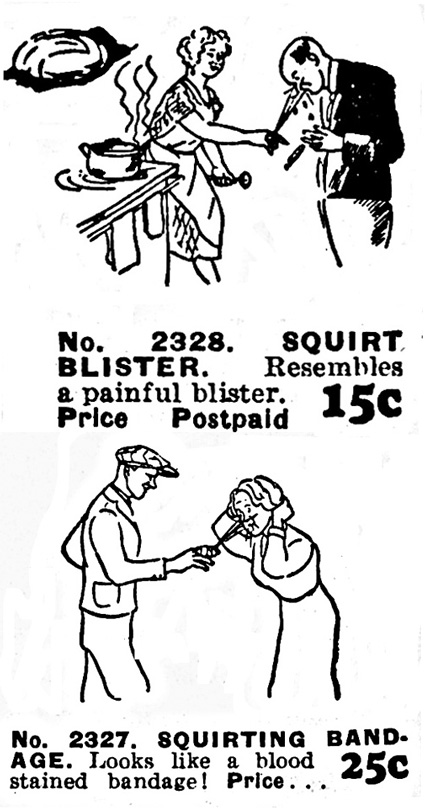

This category covers quite a few of the “standard” practical jokes: Saran Wrap covering a toilet seat, short-sheeted beds, flowers (and so many other items) that squirt water, and the classic gun that, when fired, unfurls a flag stating “bang.” I suppose fake vomit, fake doo doo, and all manners of rubber fakery fall into this category, though in some cases those things might also be a prop in a “false signaling” joke. So fake vomit of the pillow is visual, while fake vomit hidden in a piping-hot box of pizza is a surprise disruption.

Fools Errands

If you send someone to the paint store asking them to buy “striped paint” or to the department store looking for a “waterproof towel,” than you’ve sent them on a fools errand. These don’t have to be physical errands; you can also take someone on a fools ride by getting them to buy into an improbable story or unknowingly participate in a public act. When my dad worked in a hardware store, he once had a customer come in who had been told to pick up a “metric screwdriver.” Rather than reveal she had been the butt of a practical joke, he told her to come back the next day because they had them “on order.” At home that night he took a regular screwdriver and completely distorted the working end into something that looked like a Frank Gehry building. He then sold it to her and hopefully managed to turn the practical joke back on the jokester.

Hoax Stories

These jokes are for the truly gullible and can include everything from UFO stories and other supernatural occurrences, to emotionally moving personal accounts of fake heart-breaking incidents. The idea is to get the victim (or victims, as is often the case in these types of practical jokes) to buy the story and then react in an embarrassing way. When you reveal the gag, they feel stupid for not having seen through the absurdity.

Spontaneous Impersonations

Ever answer the phone to a wrong number and actually take the Chinese to-go order? Ever give out fake movie times or, at a particularly ribald party, impulsively answer the phone by saying something clever like “City morgue. You kill ’em, we chill ’em”?

Short “Why We Love The Web” Diversion

When I searched the Web for “funny ways to answer the phone,” I got 69 hits, most of them actually about “funny ways to answer the phone.” Sadly, the kind of people who make Web sites about funny ways to answer the phone are not, themselves, very funny. Here are some of their dubious suggestions:

- “Secret headquarters of Clown for Crime. Bozo speaking.”

- “Help, we’re being robbed! I – arrrggghhh…<click>.”

- “Death here. Hold on, I’ll be with you in a minute.”

- “Martin’s Mutilated Meat Market, Marvin Martin here.”

- “Hello? OH NO! The voices are back again!”

- “Bates Motel.”

- “This is Microsoft; where do you want to go today?”

Verbal Twists

Teaching a child to say something dirty for the amusement of others is in this category, as is sharing an “important” foreign phrase with someone embarking on a trip. What a joke when they tell the taxi driver that “you smell like a cheap whore house” instead of “please take me to the train station.” This category also covers funny mispronunciation gags and tricking someone into attempting an embarrassing tongue twister or having them say something inadvertently pornographic into an open mike.

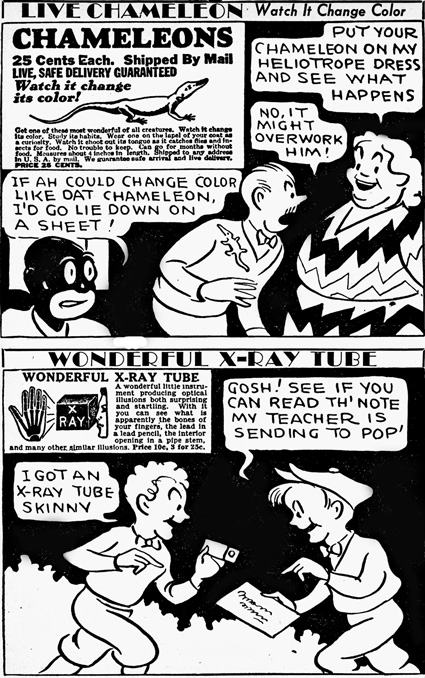

Naughty Surprises

I’m adding this category because it’s such a common theme for practical jokes. Pens that reveal naked bodies when turned upside down, classical statues that turn into urinating drunks when a lever is pulled or a button depressed, and supposed “X-Ray” glasses that contain provocative photos of naked women are a few examples of this type of practical joke. It’s hard to find these types of gags anymore because now there’s no reason to hide the “provocative” part under a box lid. But I suppose penis-shaped ice cube molds and candy made to look like condoms still fall into this category.

Subtlety is Gone

To me some of the most charming things about a 1940 practical-joke catalog have been lost to the modern gag market. Even as late as when I was a kid, you wouldn’t say “fart” in adult company. You might go so far as to hold your nose and say “pee yuuuuu.” These days if you look at any number of practical-joke Web sites (include those for Johnson Smith & Co.), one of the main tabs will be “Fart Items.”

And even though fake dog poop has been a staple of the novelty market for years, in the past you would not see a full-color “Monthly Doos” calendar, complete with sweeping nature shots where the main focus is on dog waste. Much of the risqué humor of the past was implied. You might be embarrassed slightly, but not completely grossed out, which is now the goal of most practical humor.

And these days most novelty items are photographed. I much prefer the exaggerated artwork showing shocked faces, knee-slapping laughter, and electrified reactions that was common in 1940. Part of the excitement then was not completely knowing what your dime was buying. When it came in the mail it either met your expectations, or made you feel a bit like you might have been the victim of the vendor’s practical joke. I doubt a 25-cent fake diamond looked very real, or that anyone would actually try to eat 12-cent rubber eggs. But from the drawings, you’d think so.

I suppose you could make a case that things like computer viruses or Web site sabotage are the modern equivalent of practical jokes. Some of the perpetrators certainly think so. But I’ll take a wind-up hand buzzer, squirting hat pin, or rubber walnut anytime. As they say in Latin, “In dentibus anticis frustum magnum spiniciae habes.”

This article was last modified on April 1, 2025

This article was first published on October 20, 2006

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

CreativePro Tip of the Week: Creating Dotted Lines in Photoshop

This CreativePro Tip of the Week on creating dotted lines in Photoshop was sent...

Photoshop Blur Gallery: Tilt Shift

Editor’s Note: Don’t miss the earlier articles in the Photoshop Blur...

Review : Lightroom Mobile

Review: Lightroom Mobile Pros: Automatic synchronization of edits between Lightr...