Scanning Around with Gene: Seeing Pictures With Both Eyes

When I die and go to my Heaven, it’s going to look like a store in Berkeley, California, called Urban Ore, a three-acre complex of other people’s discards that are just shy of being deemed junk. The store will also be someone else’s Hell, I’m quite sure.

You’ll find pink toilets, French doors, bay windows, and working laserdisc players at Urban Ore, along with just about anything else you can imagine someone once owning, and a few things you can’t. I go there as often as I can, for the tapestry of goods at Urban Ore is ever-changing.

On my last trip I picked up a couple of photography magazines from 1949 to 1957. There were two issues of Popular Photography, one of Modern Photography, and one just called Photography. I intend to mine these gems for multiple column themes, but what surprised me on my first pass through was the amount of ads for stereo cameras and stereo-photography gear. Click on any image for a larger version.

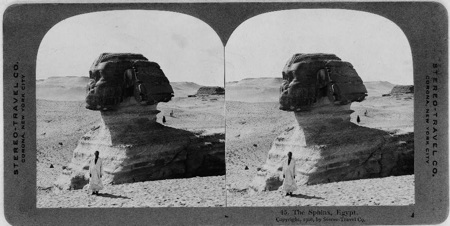

For almost as long as there’s been photography, there have been attempts to bring dimension and depth to it. Early stereo photos (the field is called stereography) consisted of two side-by-side black-and-white prints, which you viewed through a special “binocular-like” viewer called a stereoscope. Here are two examples of that style of stereo images from the Library of Congress. I’m told if you cross your eyes just the right way, you can see the stereo image without the special viewer, but I gave up when I got a splitting headache.

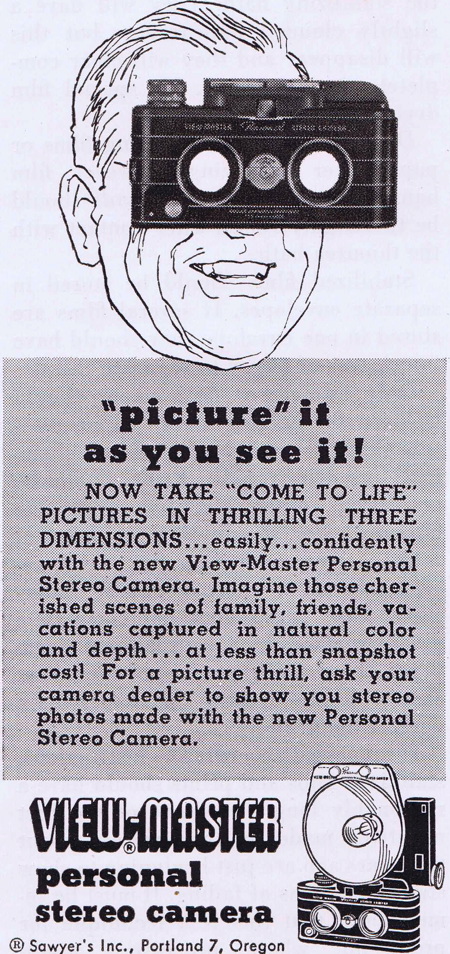

To be honest, these old black-and-white stereo images bore me once the novelty wears off. But who doesn’t love the vivid-color, cartoon-like, three-dimensional pseudo-realism of the old Viewmaster pictures-on-a-wheel? Until I looked at the photography magazines from Urban Ore, I didn’t understood how companies like Viewmaster made those wonderful images, or that you could take such photographs yourself.

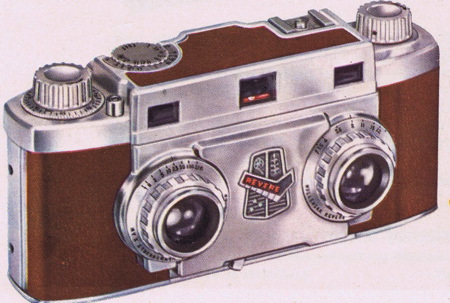

In the late 1940s, the debut of the Stereo Realist camera and viewer ushered in a mini-fad of three-dimensional home photography. Many different cameras were available to take stereo photographs, such as these I found on Wikipedia.

The trick to stereo images is to take the same picture twice, once from the position of each eye (about 2.5 inches apart). You don’t actually need a special camera to do this — you could move a single-image camera — but it’s obviously easier and more accurate to make both exposures at the same time.

This slight difference in viewing angle is what creates the illusion of depth. The science of how we see things spatially is a bit complicated (there’s a reason Avatar cost so much to make), so I won’t try to explain it, but these special cameras, combined with special viewers, did the job just fine.

As you can see, there were even attachments for regular cameras to split the image into two versions, and special flash attachments to more evenly light a scene. Quite a little industry grew up around stereo photography.

Unfortunately, the burden of special viewing devices was too great for the medium to overcome, and the fad mostly died out. We now have lenticular images, and the cinema is enjoying a 3-D resurgence, but by and large these days “stereo” is what comes out of your iPod.

It looks like it might be a fun hobby, though I’m a little bit afraid to look on eBay and see what a good used stereo camera and viewer go for. But if I ever run across these items at Urban Ore, you can bet I’ll bring them home and stack them next to all those laserdisc players I just couldn’t pass up.

This article was last modified on May 17, 2023

This article was first published on May 7, 2010

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

The Pop-Up Pinhole Project

They say necessity is the mother of invention, but it’s clear nowadays that Kick...

Framed and Exposed: Death, Taxes, and Focal Lengths

While we can all count on the inevitability of death and taxes, photographers ha...

Pentax Announces Optio S7 with Advanced Feature

PENTAX Imaging Company has announced the PENTAX Optio S7 compact digital ca...