Scanning Around With Gene: A Picture Print from Currier & Ives

I used to associate the American printer Currier & Ives mostly with Christmas. Those prints, which I disliked, seem Normal Rockwell-like in their ability to make your lip curl in disdain while sucking you in at the same time. (My apologies in advance to Norman Rockwell fans; I hope you know what I mean.) They felt very dated.

But while it’s true that many Currier & Ives images are of a winter/holiday nature, the company and the story is much bigger than that, and I’ve discovered a side to the company that is quite intriguing. Currier & Ives were very much “printmakers to the American people” and perhaps one of the first media powerhouses.

My revelation came when I dug out a couple of Currier & Ives books that I bought last year at the Marin Public Library annual book sale. Both editions were on the special “fine books” table due to their age and subject matter and were closely guarded by an entourage of library volunteers of a somewhat stern nature. Click on any image for a larger version.

And both books are, indeed, interesting works and great examples of early coffee-table editions. Here are the two title pages along with the bookplate of Margie Fitzgerald, one of the original owners. I hate to think what poor Margie or any of those stern volunteers would do if they knew I cut up pages from these books to fit them in my scanner. For Roman-numeral-challenged folks, the edition dates are 1936 and 1943.

The story begins with Nathaniel Currier, who apprenticed in a famous Boston print shop called William S. and John Pendleton of Boston as a 15-year-old lad. This shop was the first in America to make a commercial success out of the Bavarian process called “lithography,” which uses highly polished stones as plates.

By the time he was 22, Currier was not only a good printer but an ambitious young businessman. He started his own shop in 1835 at 1 Wall Street in New York City. As the business grew, it moved around Manhatttan a few times.

For many years the printer made his living selling all sorts of commercial portrait and printmaking services. Along with his brother Charles, he improved the craft of lithography.

Eventually James Merrit Ives was hired and quickly became a partner. Ives, an artist, printmaker, and bookkeeper, was the stronger of the two at business and the company began to thrive.

Currier & Ives began making inexpensive (6 cents each) prints of everyday events and places in the era before photography. They became a window to the world and into people’s lives.

But the real breakthrough came when the company started making quick “first-edition” prints of famous disasters (mostly fires). They would rush out prints as quickly as possible to sell in their shop and by agents in other locations and cities. People ate up the depictions of sinking ships, fiery buildings, and later, famous Civil-War battle scenes. Many of these images became iconic versions of real-life events.

The company also did something that clearly influenced its style — it used components from different drawings, and sometimes by different artists, to create new works. Call it early stone clip art.

Most of the images were generated in-house, but occasionally Currier & Ives used outside artists and also bought art when appropriate. They became quite the art mill and had extensive catalogs in which they describe their own work as “popular cheap prints.”

Currier & Ives had a knack for picking images that would sell well. The prints really were cheap and popular, but also well crafted and of good quality. Soon the prints were hanging in homes, schools, and barbershops throughout the states. The railroad series was particularly popular.

I appreciate that the company wasn’t all about disasters and ornamental images; it touched on spiritual and social themes as well. And many a sporting event was memorialized by the Currier & Ives art team. The speed-to-market advantage the company had through its agent network made it possible to sell images of all forms of popular culture.

When the two partners died, their sons took over the business. It didn’t take long for the sons to lead the company astray, and in 1907 the business was liquidated.

Most of the images are in the public domain, and there are many cheap reprints. However, the original prints are highly collectible.

I have a new respect for Mr. Currier and Mr. Ives. They were the first mass merchandisers of art, and they did a pretty good job. Now if only I could go back to my childhood and re-examine at all those Christmas cards. Perhaps they weren’t so bad after all.

This article was last modified on May 17, 2023

This article was first published on March 12, 2010

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Hand-Lettering Lovers, Rejoice

You may have heard Lisa Congdon’s name before. She’s an artist, illu...

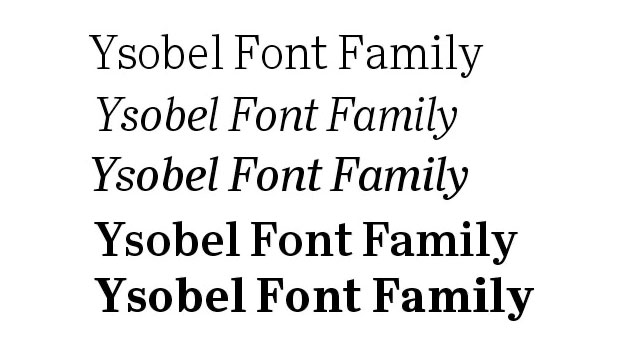

New Typeface Family Well-Suited to Newspapers, Periodicals

Monotype Imaging Holdings Inc., a leading global provider of text imaging soluti...

Design How-to: A Better Newsletter

Newsletters. It seems that every organization has them, and few designers can es...