Printing’s Brave New World: Fast Presses, Faster Turnaround at Graph Expo

After the cataclysmic events that struck New York and Washington during last year’s Graph Expo show held September 9-13, 2001, almost anything would have been an improvement. Stories about stranded travelers, airliners making abrupt landings in Lincoln, Nebraska, and long rental car treks with strangers were the staple of last year’s show.

This year the show had an air of confidence, and though housed in a smaller space than in past years, vendors were reporting that sales were “solid” or “brisk” and “better than we would have thought.”

I have attended GraphExpo (and its companion shows Converting Expo and Print) shows for decades. These shows are geared toward the printing industries — not those who want to get their projects printed, but those who do the actual printing. Heavy equipment fills the show floor and a product demnstration can be deafening as presses stir and come to life. Each year I’ve attended, I’ve gauged Graph Expo’s success by the difficulty of getting into the main show floor, and by the number of people packed in to see the latest machines from the heavy-metal stalwarts: Heidelberg, Komori, MAN Roland, and Mitsubishi. I remember one year feeling more than a bit claustrophobic while attempting to watch a demonstration of a new press with about 2,000 of my “closest associates.” I couldn’t see; I could barely breathe!

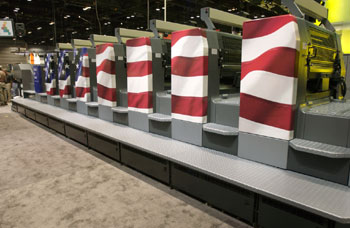

At Print 2000, Heidelberg rang a bell every time a press sale was booked. The crowd cheered along with them as the sales soared into the billions of dollars. This year’s event was more sedate, quieter, but still upbeat. I was invited to see the “top secret” new press that Heidelberg planned to unveil, and I waited in anticipation with hundreds of others as the press was shown — a beautiful 8-color, 40-inch machine adorned with a glorious American flag! (see figure 1) Though it seemed ironic to me that the German company would make an “American” press, the sentiment was right, and the audience was thrilled by the machine.

Figure 1: The seven-color Heidelberg American Flag press was a hit at Graph Expo. It proved to be the “talk of the town” at this year’s event.

Figure 1: The seven-color Heidelberg American Flag press was a hit at Graph Expo. It proved to be the “talk of the town” at this year’s event.

A few minutes later I overheard a man telling a friend, “Why, I’d love to have that machine in my plant! Hell, I’d pay extra to have that press in my plant.” Perhaps it would bring in more business — I wouldn’t be surprised.

A Surfeit of Speed and Efficiency

A friend who sells presses for Japanese press manufacturer, Komori, told me that his company had sold two presses in the morning of the first day. The press being demonstrated and another just like it had been sold to Illinois-based companies anxious to enjoy the benefits of faster make-ready and much faster operation. This was good news.

That Komori press, the new LS40 model, sports automatic plate loading and unloading, and the ability to mount and dismount plates in just three minutes. This is significantly less than manufacturers were touting just a couple of years ago. And, this new model will print at a legitimate 16,000 impressions per hour once it gets up to speed.

I have long advocated faster turn-around times as a necessary efficiency for printers, as time spent unloading and loading plates, washing blankets, and preparing the next job all falls into the category of necessary waste. Anything done to reduce turnaround contributes to net profit.

In the early 1990s I did several efficiency studies of printing plants, watching press and plate procedures, plate mounting (it was done by hand back then), and wash-up. On one four-color Heidelberg that I studied, the press change-over for four colors or inks was nearly an hour. This was a result of plates made from film (less precise than computer-to-plate systems), hand mounting (human error and differences between operator techniques), and the fact that press register was done manually.

By contrast, presses from the major manufacturers today all claim plate change-overs of less than five minutes, automatic register, and automatic blanket wash-up and preparation for the next job.

Ink-density settings were handled manually in 1990, with the operator pushing buttons on a console to control the estimated amount of ink needed on each unit, and then adjusting it once the press was running. Today’s machines gather plate coverage information either from the platesetter or from scanning densitometers, and then pass that information to automatic ink-key settings on the press console. The time it takes to get an acceptable make-ready sheet is now measured in minutes, with just a few hundred sheets being consumed to prepare the press. This is an incredible, though incremental, improvement in printing.

It is efficiencies like these that have made printing machines so different in the last decade, advancing the state-of-the art in printing production. A representative of MAN Roland told me that the physical difficulty of making a press sheet-feed paper at 18,000 impressions per hour is simply mind-boggling. Therefore efficiencies, he went on to tell me, are best made in reducing waste wherever possible.

Presses from these large manufacturers all boast speeds from 15,000 to 18,000 impressions per hour now, and even if those figures are exaggerations, these presses fly (see figure 2). If the figures are off by 25 percent and I have no reason to suggest they are, these machines are still twice as fast as presses of a decade ago.

Figure 2: The MAN Roland R500 press boasts speeds up to 18,000 impressions per hour, and is amazingly quiet. Audiences were mesmerized by this and other new offerings from the major press manufacturers.

Figure 2: The MAN Roland R500 press boasts speeds up to 18,000 impressions per hour, and is amazingly quiet. Audiences were mesmerized by this and other new offerings from the major press manufacturers.

Not an Imagesetter in Sight

As recently as two years ago, companies were showing their latest imagesetters — the machines that convert digital information into imposed lithographic film — ready to make printing plates. At this year’s show I couldn’t find a single imagesetter. Not one (I did see an ad for refurbished imagesetters at one booth).

Taking their place were dozens of new platesetters. Big ones, small ones, medium-sized units. Some use infrared lasers, some use carbon dioxide, some use heat, some use visible light. Where a few years back there were only three or four on the market, and those machines were priced at $250,000 or more, at this show there were platesetters for 29-inch presses priced less than $70,000. This puts the platesetter squarely into the plans of medium-size printers, and puts the value of these machines into the benefits column of nearly any printer in the category.

The cry that “film is dead” was never more true than at this year’s show. Nobody was looking at film, no one that I saw was making plates from film. It was a subject far from the headlines of the 2002 event.

And Hardly a Scanner to Be Seen

In addition to the noticeable absence of film-related technology, I saw almost no prepress scanners. Though Heidelberg still makes and supports one drum scanner, I didn’t see one in their booth, and I saw none in other booths. I asked an Xpedx salesman about this and he indicated that he had sold only a few in the past year. “Either everyone already has one, or nobody needs one,” he told me with a chuckle.

It’s obvious that the focus of image capture has shifted to digital cameras. Several companies at the show were exhibiting high-resolution digital cameras for the capture of still images. And there was “buzz” about new still cameras expected soon from Kodak, Nikon, and Canon that will generate 30-plus megabyte images of very high quality. Obviously another corner has been turned when such devices eliminate the need for film altogether (I haven’t shot film for more than two years).

Dumb Ways to Get Attention

The booths as usual had their share of foolishness. Screen had a juggler on stilts in its booth, Creo had a show featuring men and women doing mime in blue-face (see figure 3). The busty women who are typically hired to attract men to trade show booths (there were two this year) each had a diamond navel adornment (I checked). In general, the show was free of tacky come-ons, and the attitude was professional and down-to-business. The crowds were light enough that I was able, on a couple of occasions, to get a 45-minute demonstration of software, something that would have been difficult in years past. This was a refreshing change for me, and I enjoyed having “quality time” with several vendors.

Figure 3: Creo’s GraphExpo booth featured a crew of four blue mimes. As you can see from the size of the audience, it was a non-starter. However, lots of attention was paid to Creo’s products in the booth behind the performers.

Figure 3: Creo’s GraphExpo booth featured a crew of four blue mimes. As you can see from the size of the audience, it was a non-starter. However, lots of attention was paid to Creo’s products in the booth behind the performers.

A New Proofer from Creo

Creo, which earlier this year dropped “Scitex” from its company moniker, announced a new Iris proofer called Veris, which is able to be run as a stand-alone unit, or connected to Brisque, Prinergy, and other productivity systems (see figure 4).

Figure 4: Creo’s new Iris Veris proofer features 1,500 x 1,500 pixel resolution for proofing. The unit can be operated as a stand-alone machine, or connected to a prepress system.

Figure 4: Creo’s new Iris Veris proofer features 1,500 x 1,500 pixel resolution for proofing. The unit can be operated as a stand-alone machine, or connected to a prepress system.

Where previous Iris printers struggled with fine details and hairlines with 300 dpi resolution, the Veris has 1,500-dpi resolution, and in the samples that I saw, features clean, clear detail on 5-point type. Also gone is the persnickety nature of the Iris machines. Veris comes in a package that resists humidity trouble, and it holds on to the proofing substrate more firmly than any of its predecessors.

Ink-jet printers from Hewlett Packard were evident at the show in several booths. Epson also made a splash with their latest offering, a seven-color (CMYK, light M, light C, light K) high-speed (and high-resolution) ink-jet printer called the Epson 10600. Combined with reengineered inks and substrates, this device has a stunning color gamut, and the speed to produce prints and proofs in very few minutes. Several RIP makers, EFI, Best, Xitron, Xinet and others were competing for attention making gorgeous proofs on these and other wide-format machines. The need for an all-digital proof was not lost on this audience.

Indigo, Where Did You Go?

In a move that likely saved the clever Indigo press from doom, Hewlett Packard stepped in with a near one-billion-dollar purchase of the Israeli company this year, making the Indigo into a Hewlett Packard printing press (see figure 5). This is the first time HP has presented itself on the same footing as Xerox, Heidelberg, and Xeikon with a machine that it positions to compete with the iGen, the NexPress, and the various Xeikon toner-based digital presses.

Figure 5: HP’s demonstrator tells the audience about the Indigo WS 4000 press at Graph Expo 2002.

Figure 5: HP’s demonstrator tells the audience about the Indigo WS 4000 press at Graph Expo 2002.

HP’s implementation of Indigo’s technology was one of the more impressive displays at the show. They showed an HP Indigo WS 4000 web-fed label press connected to a converting machine made by Omega Systems that featured foil-stamping, embossing, die-cutting and roll-separation on pressure-sensitive stock (see figure 6). The combined machine was running variable-image wine labels on the fly, delivering them on a roll, ready for adhering to bottles of the finest wines. This technology got a lot of attention, as did HP’s enhanced presence as a major vendor at the show.

Figure 6: The converter connected to the HP Indigo WS 4000 web-fed digital press. This unit was converting the printed material into pressure-sensitive labels.

Figure 6: The converter connected to the HP Indigo WS 4000 web-fed digital press. This unit was converting the printed material into pressure-sensitive labels.

The other digital press offerings mentioned (iGen from Xerox, NexPress from Heidelberg) were also getting a lot of attention (see figure 7). These machines all have done a lot of growing up since the last time we looked. Each one has qualities comparable to “real” printing. Each can print large sheets (11 x 17 full-bleed) at commercially viable speeds, and each one is capable of true variable-data and variable-version printing. I saw no need for excuses for quality from any of these machines, and I see the future looking bright for this digital printing technology.

Figure 7: The Xerox iGen 3 is a full-color digital press, capable of variable-data and variable-version printing. A blend of technologies developed by Xerox and its partners, this unit, and competitive devices from Heidelberg, HP Indigo, and others deliver digital on-demand color printing to the pressrooms of tomorrow.

Figure 7: The Xerox iGen 3 is a full-color digital press, capable of variable-data and variable-version printing. A blend of technologies developed by Xerox and its partners, this unit, and competitive devices from Heidelberg, HP Indigo, and others deliver digital on-demand color printing to the pressrooms of tomorrow.

DICOweb on Display

MAN Roland was the first to implement Creo’s SP technology, first shown at the show in 2000. The DICOweb press was shown (only one unit) at this year’s event. This press has the ability to coat, and then expose and process printing plates on the press. I feel that this technology is better suited to sheet-fed machines, but remain impressed (if you’ll excuse the pun) by the idea of a press that is able to make its own plates with a permanent stainless plate cylinder. To me this represents the most efficient platemaking technology to date.

Smaller, Smarter, More Productive

In the time I had to spend at the show I was not able to complete the whole circuit. But the technology I saw made me realize that while the economy is not rocketing skyward (an understatement), business in the printing industry is good. A smaller, more compact Graph Expo made me feel like things are on the mend. And, frankly, I wouldn’t mind having a beautiful German-made press with an American flag painted on it in my shop. I’d pay extra for that!

This article was last modified on December 13, 2022

This article was first published on October 22, 2002

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Scanning Around With Gene: Born in 1956

For my birthday a few weeks ago, I received a complete set of National Geographi...

Big Problem with FindChangeByList (and an easy fix)

The FindChangeByList script is a marvel, and I’ve used it many times to clean up...

When Is a Dragon a Delightful Design?

Louis Fishauf, Canadian designer and illustrator par excellence, has created two...