Multilingual Publishing with InDesign

Learn the tools, scripts, and methods that make multilingual publishing possible with InDesign.

This article appears in Issue 85 of InDesign Magazine.

Expanding Your Linguistic Horizons

Most of us probably don’t break a sweat when typesetting in English, French, or Spanish, but what happens if a customer asks us to incorporate some other foreign languages into our layout? Do we head for the hills, or do we add some tools to our toolbox and expand our capabilities? It sounds like a no-brainer to me that you would want to expand your tools, as we are living in a fast-paced publishing world where the competition is fierce and the budgets are tight.

Setting Expectations

Before we look at tools and scripts and other magical methods of multilingualism, let’s set correct expectations. You see, technically there is nothing stopping you from typesetting hundreds of pages in various languages, given the capabilities that Unicode operating systems, OpenType fonts containing more glyphs than you can shake a stick at, and of course our beloved InDesign have to offer. But unless you are a native speaker of said language or languages, you might be setting yourself up for the shortest customer–supplier relationship ever. So let’s get started with a couple of tips: Choose your language wisely. Though all languages will provide challenges, some languages are just easier to handle than others. Russian can be typeset in InDesign without any additional tools or scripts. Though Arabic may look intimidating at first, it is actually relatively easy to work with. Languages like Chinese and Hindu are on the more difficult side of the spectrum, and Japanese is just… Well, let’s just say you don’t want Japanese to be your inaugural language in the world of multilingual publishing. Work with a proofreader who is a native speaker. Russian may be easy to work with in the sense that it it does not require any additional tools other than a

good OpenType font with the necessary Cyrillic characters, but it also has some specific requirements that InDesign does not handle very well. As such, when working with languages, it’s of vital importance to have a good proofreader who is a native speaker/reader of the language so they can help ensure you don’t make costly mistakes. After all, you have no idea what you are putting on the page or if InDesign is doing a good job of breaking and hyphenating. Start small. Though you may technically be able to lay out hundreds of pages in a foreign language, it is probably best to not dive head first into this pool of glyphs. Dip your toe in the water first, and start small. Less risk is always good. And don’t forget the previous bullet. Be prepared to use character styles. The No Break function and language-specific character styles are musts in a multilingual workflow. Though GREP can help, some manual application of character styles is inevitable. Did we mention you should work with a native speaking proofreader? I believe we did, but I am mentioning it again. Because if you don’t, you should be prepared for some tough questions from your customer.

InDesign and Regions

Having lived in quite a few countries and a been a frequent traveler, I know that language offers a way to connect, regardless whether you know only the basics or are a fluent speaker/writer. For example, 你好 stands for nĭ hăo, or ‘Hello’ in Chinese, and always serves well to get you started, even if you know nothing else. A quick Google search tells me that there are currently an estimated 6500 spoken languages, of which about 4000 also have a written form. In terms of InDesign, we can distinguish a few language groups.

The “standard” version of InDesign

The standard version of InDesign is ready to work with left-to-right languages, which include but are not limited to these subgroups: Western European: These languages are closely related to English and include French, Spanish, German, and Italian. Most fonts should have all the glyphs required to typeset in these languages, which use the roman alphabet and the Adobe Paragraph composer. Central European: Still closely related to English, these languages include Polish, Czech, Lithuanian, and even Turkish. They use the roman alphabet, but also a lot of specific accented glyphs such as ş, ą, or ł that may not be available in every font you use. These languages use the Adobe Paragraph composer. Greek and Cyrillic: Neither of these use the roman alphabet, and both have such extensive character sets that most regular fonts will not suffice. OpenType is pretty much a requirement to work in these languages, and you will also need to investigate and make sure your font of choice supports Greek and Cyrillic. These languages use the Adobe Paragraph composer. Indic and South-East Asian: These languages do not use the roman alphabet and include Hindi, Vietnamese, and Thai. They have an extensive character set requiring specific fonts and also require the Adobe World Ready composer.

InDesign ME (Middle Eastern)

The Middle Eastern languages have a challenging set of requirements. First, you need to use fonts with appropriate character sets, the because these languages use a different alphabet comprised of Arabic or Hebrew. You also need the Adobe World Ready composer and the ability to set text right-to-left. The good news is, technically speaking, all versions of InDesign have right-to-left functionality built in. What this means is: if you receive an InDesign document from someone in the Middle East, you can open that document with your “regular” version of InDesign and everything will be rendered correctly. However, it requires a specific version of Adobe InDesign to actually have an interface for the right-to-left features or a third-party utility that brings them out of hiding. We will discuss the various ways to access the Middle-eastern specific features later in this article. InDesign CJK a.k.a. Chinese (Traditional & Simplified), Japanese, and Korean Typesetting Arabic and Hebrew may make you a bit uncomfortable, but at least they still have an alphabet with a relatively limited character set. Just wait till you actually have to do some Chinese, Korean, or Japanese typesetting; that’s when the fun really starts! You will very likely need additional fonts beyond what is delivered with InDesign, you need the Adobe Japanese composer, and even though many of these languages do run from left to right, some of them may not only be vertically typeset but also from right to left. In other words, CJK may be the toughest of all. As with Middle Eastern languages, the requirements are very specific, and as such you will need the right set of tools to deal with them properly.

Working with Languages in InDesign

Let’s consider some of the tools and options for working with multilingual content in InDesign. I am working under the presumption that you are not interested in setting just one line of text in Arabic or Japanese but that you are really aiming to set anything from a paragraph to a page or maybe even a few pages. As such, I am ruling out free scripts that exist to switch character direction or copying and pasting from an existing InDesign file typeset with an ME or CJK version of InDesign as workable options. Based on your requirements, there are two main roads open to you. Use a third-party plug-in: Remember that any version of InDesign since CS5 has the core capacity to deal with “other” languages, but the interface offers no way of setting the required parameters. Third-party plugins at the very least enable these interface elements, while offering other options as well. At this time there are two main suppliers of plugins for working with multilingual output in Arabic: World Tools from In-tools and ScribeDoor from WinSoft. In terms of composing both Arabic and CJK, there really only is one plugin: World Tools Pro from In-tools. Install Arabic or CJK versions of InDesign: Back in the day, you had to purchase separate versions of InDesign to be able to work with Arabic and CJK content. With the introduction of Creative Cloud, life has gotten much easier, and installing a different language version is as easy as following five steps, outlined by Adobe in this support article.

So which road do you choose?

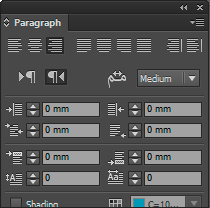

As is often the case, both paths come with their own advantages and challenges. If you plan to set large amounts of text in foreign languages and you use Creative Cloud, then you might be tempted to save money and use this procedure to install complete versions of InDesign, and that may seem to be a good idea. Choosing the English (Arabic) or English (Hebrew) option installs InDesign ME, which essentially adds options to panels and installs additional fonts, but your interface is still English (Figure 1).

Figure 1: In the Arabic version of InDesign, the Paragraph panel adds features specific to right-to-left typesetting, but the interface remains English.

Unicode and OpenType

Let’s take a step back and talk about Unicode and OpenType, as these standards form the foundation for making multilingual publishing possible. As the name implies, Unicode is an international encoding standard that is used with different languages and scripts and that has the bi-directional support that is so important to Arabic and Asian languages. If you really dive into it, Unicode is quite complex, but in essence it’s nothing more than a very big table that gives over 120,000 characters each an exact and unique four-character alphanumeric value. You can find charts on the website of the Unicode consortium that tell you exactly what value a certain character has. Since computers love codes, this works brilliantly to ensure that any computer system that supports Unicode shows the same symbol, be it in Word, a browser, or—of course— InDesign. For example, the humble pilcrow has a Unicode value of 00B6 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Using the Glyphs panel to search for Unicode values. Hover over a glyph to see the Glyph ID or Unicode value.

Unicode Tips

Searching for glyphs in InDesign CC2015: The November update of CC2015 (11.2) introduced a couple of new features for working with glyphs, but one of the absolute gems is the ability to search by name or Unicode value in the Glyphs panel. Be aware that this search applies only to the font currently selected in the bottom left of the Glyphs panel. It would be a great addition in a future version of InDesign if you could search all fonts that contain a Unicode character. Finding a Unicode value: But what if you don’t have CC2015? The charts on the official Unicode webpages are very detailed but also very hard to search. Though there are quite a few websites that provide searchable Unicode overviews, one of the best is unicode-table.com. Use the search feature by typing a keyword, or scroll continuously to find the glyph you’re looking for, and hover over a symbol to learn more about it. Then check out InDesign Magazine issue 41, which has an article called “Tracking Down Obscure Glyphs” (excerpted at CreativePro.com) that provides a workaround for inserting a glyph by number. Or, you could use this free script from Rorohiko. Not sure how to use scripts? There’s an article for that too. GID vs. Unicode: Any character in Unicode has a unique alphanumeric value that represents the same character across multiple systems. The GID or Glyph ID essentially determines the position of a glyph within a given font and as such is not unique. The same Unicode character can have different Glyph IDs in different fonts.

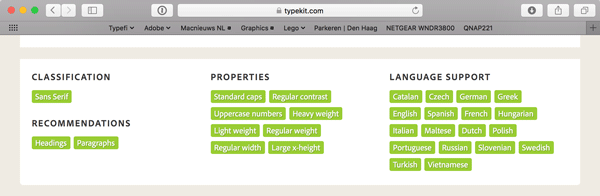

Back to the other foundation I mentioned above: OpenType, a font format designed primarily by Microsoft with support from Adobe to replace TrueType and PostScript Type 1 formats. It was meant to have the advantages of TrueType (cross-platform compatibility and other technical “stuff”) while offering a lot more glyphs: 256 × 256 = 65,536 to be exact. I firmly believe that in this day and age PostScript Type 1 fonts should be avoided at all costs, though as with EPS there are undoubtedly exceptions where you would still use them. For multilingual publishing with large character sets, using an OpenType font is the sensible thing to do. However, I would like to issue a warning and a very important one: just because a font is labeled as OpenType does not mean it actually contains the required glyphs for multilingual publishing! Some font foundries simply repackage a TrueType font with 265 characters as an OpenType font. In other words, make sure the font you intend to use actually contains the characters needed for a particular language. If the font is synced via Typekit, you can can check its language support on the Typekit website (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Details on Source Sans Pro on the Adobe Typekit website showing the languages supported by this font.

Don’t Forget the Glyphs panel

If you can’t find information about your font on a website, it’s the Glyphs panel to the rescue! To confirm whether it contains the characters you need, select text in the font you wish to verify. Open the Glyphs -panel (Windows > Type And Tables > Glyphs) and make sure Show: Entire Font is selected. If you want, increase the preview size using the icons at the bottom right. You can now see all the characters available in the font. Also, check out Steve Werner’s great article at InDesignSecrets, How to Find the Font That Has the Glyph You Need.

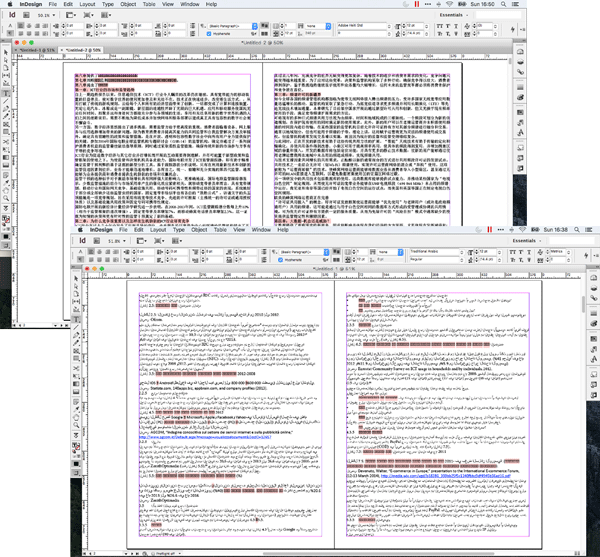

Getting your Content into InDesign

We now have some background knowledge about dealing with languages, so let’s take the next step and actually get some stuff into InDesign. At this point you might think it is really hard work, but it is actually surprisingly easy to get your multilingual content into InDesign. Just like with “regular” English text, use InDesign’s File > Place command, and select the text file containing your content. Place it like you normally would and presto, you are a multilingual publisher! Even without any third-party tools or language-specific versions of InDesign, CS5 and later comes with enough fonts to place a large portion of the text (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Proof you can place multilingual content quite well without additional tools.

No typing or translating

You might notice I do not talk about any other ways of getting your content into InDesign other than File > Place. There are several reasons for this. First, using the Place command ensures the text is correctly processed by InDesign (unlike pasting, which can cause problems). Secondly, typing content in Thai, Hebrew, or Hindi—though theoretically possible— is not practical at all, especially for a non-native speaker. Thirdly, InDesign cannot turn one language into another, just in case you had that idea. Your content needs to be in the correct language to begin with.

Multilingual = Multiplied Opportunities

Producing multilingual content is not necessarily more difficult than producing content in your native language. The foundation for many languages is available in InDesign, technologies such as Unicode and OpenType make it relatively easy to handle different characters, and with a small investment you can expand the language support greatly. Naturally there is a requirement to learn about the details of a new language, and it is absolutely vital that you have a native speaker of the language to proofread your content before you deliver it to your customer. Truth be told, I do not expect you to be able to produce long documents, but the next time a customer asks you to incorporate multiple languages into a project, you will be able to weigh the pros and cons and expand your business!

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

New Contest! The Puzzling Pasted Text

Solve this InDesign mystery for a chance at winning a great prize.

Beware of groups “on the edge”

While editing a file created by someone else, I selected a group, pressed comman...

Turbo Photo Announces Mini-collection Stock Photo CDs

Turbo Photo (www.turbophoto.com) announces a new series of stock photo CDs calle...