InType: Know Your Small Caps

Add sophistication and polish to your type by understanding the different kinds of small caps, as well as how and when to use them.

This article appears in Issue 62 of InDesign Magazine.

In today’s “do-it-yourself” digital world where most designers are called upon to spec, style, and set their own type, learning how to finesse your typography is crucial to achieving professional results. One typographic element that is often misunderstood, overlooked, and occasionally misused is small caps. What are they? When and how should you use them? Where do you find them? Whether you find yourself one of the perplexed or just wish to refresh your knowledge of the topic, read on to become a bit more typographically enlightened!

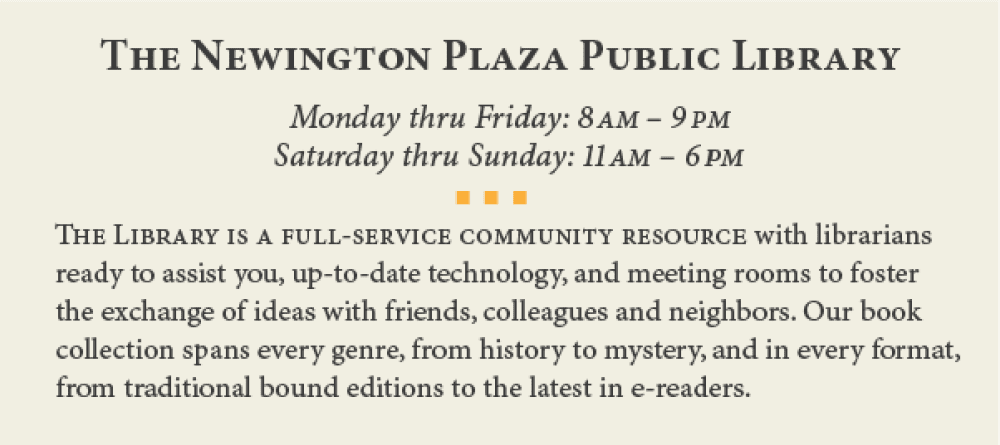

Small caps are uppercase letterforms that are shorter than cap height. In a typeface intended for text, small caps most often approximate the measure of the x-height, so they blend in with the lowercase characters. Small caps for display or more decorative designs have more flexibility, and can be taller than the x-height (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: The height of true-drawn small caps can vary from typeface to typeface. Some designs, such as Alfon, have small caps that are created to blend with the lowercase; others, such as ITC Braganza, have small caps that are meant to be companions to the full caps.

Figure 2: Alfon (on the left) has small caps that are the same height as its lowercase, while Braganza’s small caps (on the right) are taller than the x-height.

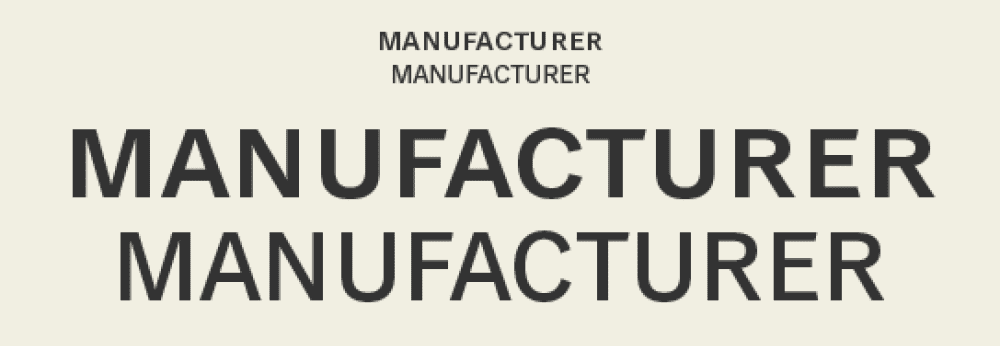

match the weight, proportion, and overall color of the caps. Computer-generated small caps, on the other hand, are just reduced capitals, and therefore look too light, too tightly spaced, and in some cases, too narrow (Figure 3).

Figure 3: True-drawn small caps (left column) and computer-generated small caps (right column). Computer-generated, “fake” small caps are just reduced caps and therefore look too light (and often too narrow and too tightly spaced).

Figure 4: Small caps work well in a number of scenarios, including headings, abbreviations (such as AM and PM), and lead-ins.

Figure 5: The differences between all caps and small caps set at the same height (here set in Classic Grotesque™) can make for a more legible treatment for cap text at small sizes.

Accessing True-Drawn Small Caps in InDesign

An increasing number of OpenType fonts come with true-drawn small caps, but knowing which have them and how to access them can be a bit confusing. InDesign has two options for converting text to small caps, but each behaves differently (Figure 6):

- The Small Caps setting in the Character panel’s flyout menu (or the Small Caps button in the Control panel) will convert only the lowercase letters in selected text to small caps—the true-drawn variety if available in the chosen font, or the fake, computer-generated ones for fonts that don’t have the real thing. It will leave the full caps unconverted, resulting in a combination of full caps and small caps.

- The All Small Caps setting in the OpenType submenu accessed from the Character panel will convert all characters in selected text to small caps, including the full caps, resulting in a total small cap setting. Note that this feature is only accessible—and therefore unbracketed—for OpenType fonts that contain true-drawn small caps. It will never generate the fake variety.

Figure 6: The differences between all caps and small caps set at the same height (here set in Classic Grotesque™) can make for a more legible treatment for cap text at small sizes.

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

The Making of a Typeface

Rob Keller took almost three years to design the Vesper typeface. He chronicles...

Scanning Around With Gene: Old News is Good News

There are a lot of perks to being a highly paid blogger here at CreativePro. The...