How to Adjust Display Color for Creative Work

Help your display reach its potential.

This article appears in Issue 42 of CreativePro Magazine.

To many, a computer display (video monitor) is the ultimate set-it-and-forget-it device: They plug it in, power up, and rarely think about it again. That’s fine for general use, but what if your work is color-critical? If you apply a neutral 50% gray in Photoshop, you expect to see that exact 50% neutral gray on the screen. Your clients expect accurate color in your designs, too.

Although better than they once were, displays aren’t always perfect out of the box—and accuracy can drift over time. Pros and educators will tell you that the best practice is to calibrate your monitor. Solid advice—except that what it means to calibrate has changed rapidly in the last few years. That’s partly because some newer computer displays have more-advanced options that older calibration tools don’t account for.

So, how do you know you’re getting the full color potential of your display? This guide will help you navigate the issues.

How Does Color Calibration Help?

Calibrating a display measures how accurately it reproduces a range of colors and gray tones. Suppose you measure your screen using a color calibration sensor; it might report that when you apply 50% gray, which is sent to the display as RGB color values R: 128, G: 128, B: 128, the monitor actually displays R: 128, G: 127, B: 129—a slight color cast. The operating system then can use this and other measurements to precisely correct the colors sent to the display so that the colors you see on screen match the color values you asked for.

The “best way” to calibrate depends on the kind of display you have.

What Kind of Display Do You Have?

Today’s displays fall into three general classes:

- Basic. Still

the most common and affordable type of display, these might cover the sRGB color gamut. Brightness might be the only color-related adjustment. - Wide gamut. These displays can reproduce most or sometimes all of the P3 or Adobe RGB color spaces, both of which are much larger than sRGB. They may offer built-in presets representing the standards for specific creative work such as photography, graphic design, and video. Once rare, wide-gamut displays are now more common and affordable. For example, almost all current Apple displays on desktop and mobile are now wide-gamut color.

- Pro color. These displays typically combine more precise factory color calibration with wide-gamut color reproduction, color presets, and the ability to be color calibrated at the hardware level. (I’ll soon explain what that means.) Some examples of pro color display product lines are Eizo ColorEdge, BenQ SW, Apple XDR, Asus ProArt, and NEC SpectraView (now discontinued, but many are still in use).

These three category names are mine, so you won’t see them at the store. But thinking of displays in this way can help you understand the type of model you have and how to calibrate it.

What Calibration Target Should You Use?

Be aware of the color viewing settings your work should conform to. When calibrating, this is called the calibration target, because it’s what you’re aiming for. A color standard can include color gamut, white point (color balance), luminance (brightness), and tonal response curve (TRC), which defines how tones are distributed from light to dark. Here are some examples of how your calibration target might change:

- If you mostly create images for websites, it’s useful to view them in the sRGB color space.

- If you mostly edit video, you may need to meet one of several specific professional reference viewing standards depending on the project you’re working on.

- If you’re editing for a CMYK commercial press, to match printed proofs you might be required to view images on a display calibrated to a specific prepress standard.

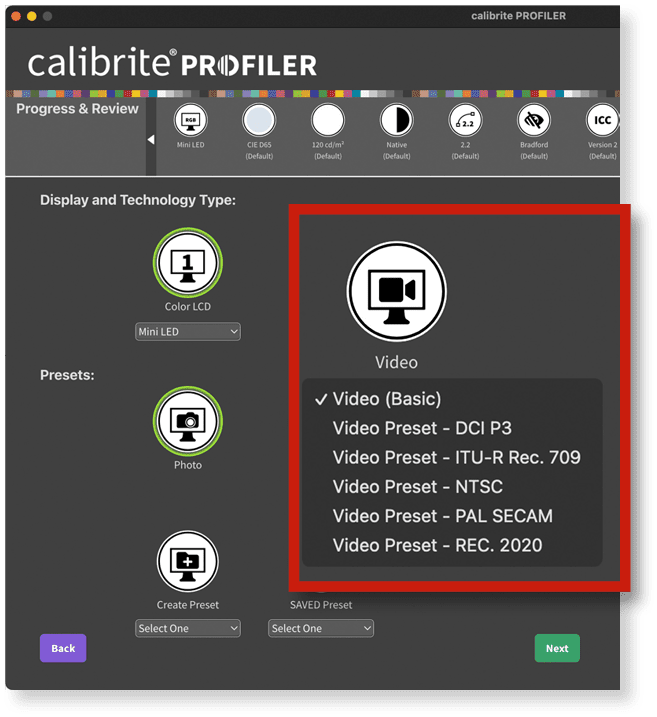

Calibration software typically offers calibration target presets for some of the more popular color settings (Figure 1). You can usually create a custom calibration target preset that matches your requirements.

Figure 1. Calibration software usually offers commonly used calibration targets as presets organized by workflow or device. Simply select or customize one of them.

One reason you might customize a calibration target is that there can be different standards within each medium. For example, if you edit video, the standard you follow would depend on whether you’re editing older video, 4K video, or HDR video, as well as on the standard your client might require. Likewise for print, some production workflows might recommend setting the display to the D65 white point, which simulates bright daylight; others might use the warmer D50.

How Should You Calibrate Your Display?

The way you should calibrate depends on the kind of display you have.

Does your display support hardware calibration?

If your display supports hardware calibration (less common and more expensive), and it came with a compatible color calibration sensor and the software to run it, use them to calibrate. The calibration software will lead you through the steps of placing the sensor on the screen and completing the calibration. Because it’s hardware calibration, the software can communicate directly with the display to make the needed adjustments. Those corrections will be stored in the display hardware itself.

Does your display come with built-in color presets?

If your display offers built-in color settings presets that you can switch using buttons on the display (Figure 2), you’ll benefit from choosing the correct preset before you perform a software calibration; see the sidebar “Examples of Color Viewing Settings.”

Figure 2. Some displays offer a menu of built-in color presets.

If your display can reproduce the wide P3 color gamut, for example, and it offers color presets, first use the controls on the display to apply a P3 preset. You want to avoid a situation where you want to calibrate the display to P3, but a preset is applied in the display that limits it to sRGB, preventing its entire P3 gamut from being in effect when you run the software calibration.

(With hardware calibration this shouldn’t be a problem, because the calibration software lets you set it to automatically adjust the display hardware according to the settings.)

What if the display doesn’t support hardware calibration or built-in presets?

If you have a basic, low-priced display, it might not support hardware calibration or have built-in color presets. In this case, you can run calibration software with a color measurement sensor. Keep in mind, too, that a low-priced display that’s calibrated could potentially reproduce color better than a higher-priced display that hasn’t been calibrated recently.

When you enter calibration target values for a lower priced display, don’t be surprised if the software offers fewer choices than you expected. For example, you might not see a color space option if the display covers only sRGB and not wider color gamuts.

What if you don’t own a color calibration sensor?

If the display offers built-in color presets, choose the one that most closely represents your calibration target settings. If the display doesn’t offer color presets, you’ll simply use it as it is.

The downside of not owning a calibration sensor is that there’s no way to measure displayed colors to see if they’re still accurate. If those are inaccurate, any display color presets won’t be accurate. So, if you don’t own a calibration sensor, accuracy depends how well the display was calibrated at the factory, which varies a lot. Over time the display might also drift from its initial calibration, reducing color accuracy.

Can you use an old calibration sensor?

If your calibration sensor is more than a few years old, it might be designed for CCFL-backlit LCDs and CRTs. It might not be compatible with newer display technologies such as HDR, OLED, and Mini LED. If you buy a new display that uses any of those technologies, check to make sure your current color measurement sensor is compatible. If it isn’t, you may need to upgrade to a current model to get the best color out of the latest displays.

How about calibrating by eye?

Some software lets you calibrate by adjusting your display as you look at calibration graphics, but using your own eyes isn’t considered reliable for professional work. How we humans see a color or tone depends on the colors or tones next to it; we’re susceptible to contrast illusions such as the classic checker shadow illusion. In part this is because human vision evolved to be highly adaptive and subjective, which helped us survive in the wild. So for adjusting a display, a calibration sensor is much more precise and objective.

There are some exceptions. For example, when we try to match color on two displays or when we try to match a display to a calibrated print viewing booth, doing so strictly by the numbers doesn’t always achieve a match. Some displays have a feature with a name (such as “visual fine tune” or “color trim”) that lets you make a final visual match. But as the names imply, these features are meant to be used as a finishing step, only after a calibration with a color sensor has applied accurate fundamental corrections to the display.

Set Expectations Appropriately

Color calibration can improve a display only up to the limits of its capabilities, such as its maximum color gamut and luminance. It’s sort of like if a sports coach asks someone to run a certain distance in 10 seconds: Whether a particular person can do so depends on their physical condition. Like a pro athlete, a pro color display tends to be more capable of reaching the target performance.

Similarly, calibrating a display does not by itself guarantee that colors will match another device or a print. For example, if you calibrate to any of the widely used RGB color spaces (sRGB, Adobe RGB, or P3) it will be possible to create and see colors on the display that are outside of the color gamut that any ink and paper combination can reproduce.

To get the best preview of how colors look under different output conditions, also learn how to soft-proof (restrict the display to the output color conditions) in your creative software, or even better, in the display itself. (Soft-proofing isn’t available in all applications and displays.)

How Are Hardware and Software Calibration Different?

The results of hardware calibration and software calibration may seem about the same on the surface, but there are some potentially important differences.

Where the color corrections happen

During software calibration (Figure 3), the calibration software stores the color sensor’s measurements in a display color profile that it installs and activates in your computer’s operating system. (If you haven’t calibrated your display, the current display color profile is probably the one set at the factory.) The OS uses the measurements in the display profile to send adjusted color values to the display, so that you see more accurate colors.

Figure 3. During software calibration, you place the calibration sensor on the display and run the calibration software (A). The software stores the measurements in the display profile (B), which the OS uses to correct color values sent to the display.

During hardware calibration, the calibration software saves the corrections directly into the display hardware (Figure 4). This means the corrections don’t depend on the profile, so that changes its role. Now the profile only has to report to the OS about the calibrated state of the display.

Figure 4. Hardware calibration is mostly done the same way as software calibration (A), but the software stores the corrections in the display hardware (B).

Easy switching among calibrations

Displays that support hardware calibration typically let you store multiple color calibrations in the display hardware. This is nice if you do work for projects with different color requirements, because you can instantly switch among calibrations on demand.

If a display can store multiple calibrations and you switch among them, the display color profile selected in the OS needs to be changed to match. If the display lets you switch calibrations using its display management software (Figure 5), typically that software also switches to a matching display color profile in the OS automatically, so that the OS continues to send color values that match how the display is set up.

Figure 5. In this example, when using the Target Settings menu in NEC SpectraView II software to switch among the calibrations that can be stored in the SpectraView display hardware, the software also switches the OS to the display profile that goes with that calibration. (That part isn’t shown.)

Higher quality color calibration

In a display that supports hardware calibration, its internal color processor can typically adjust its colors with more precision than when the OS does the corrections in software using the display profile.

Hardware calibration benefits any source you plug into the display

Because the color correction is in the display, the correction benefits other devices you connect to the display such as computers, tablets, and media players.

With software calibration, the calibration applies only if the display profile is in effect, which means it really only applies when you connect a computer and the appropriate display profile is selected in the OS.

Better proofing

You can set up some pro color displays to simulate the characteristics of specific types of media delivery. For example, you may be able to load a color profile that represents a specific combination of printer, inks, and paper, and the display can use that profile to simulate on screen how a document’s colors will appear on those prints.

If this sounds similar to the soft-proofing feature in many graphics applications, it is, but it is built into the display hardware for higher quality. Being able to directly set up a display this way also makes it possible for you to soft-proof colors when you use the many applications that don’t have a soft-proofing feature.

Different options for calibration sensors

For a basic or wide gamut display, you can perform software calibration using a range of affordable color profiling solutions from companies such as Datacolor and Calibrite. For a pro color display that supports hardware calibration, there are fewer choices.

You must use calibration software and a color measurement sensor that can work together and communicate with the hardware in your specific display. When you buy a pro color display with a compatible color measurement sensor and calibration software, you won’t have to try to match them up yourself. In some displays, the color measurement sensor is built in.

How Often Should You Calibrate?

If you asked “How often should you calibrate?” 25 years ago, the answer might have been “every week” for professional work. When media creation first went digital, the fat, heavy, cathode-ray tube (CRT) monitors drifted easily, so they required frequent color calibration.

As flat-panel displays became popular, they progressed from cold cathode fluorescent lamps (CCFLs) to today’s light-emitting diode (LED) backlights and organic light emitting diodes (OLEDs) that emit their own light. Compared to CRTs and CCFLs, LED backlights last longer and are much more stable, so you might have to recalibrate only every few months.

How Many Years Can You Use a Display?

Your software probably provides a report at the end of a calibration run. You can check it to see if the display is still accurate enough to use for professional work and to see if the calibration target settings used at the factory are consistent with your workflow.

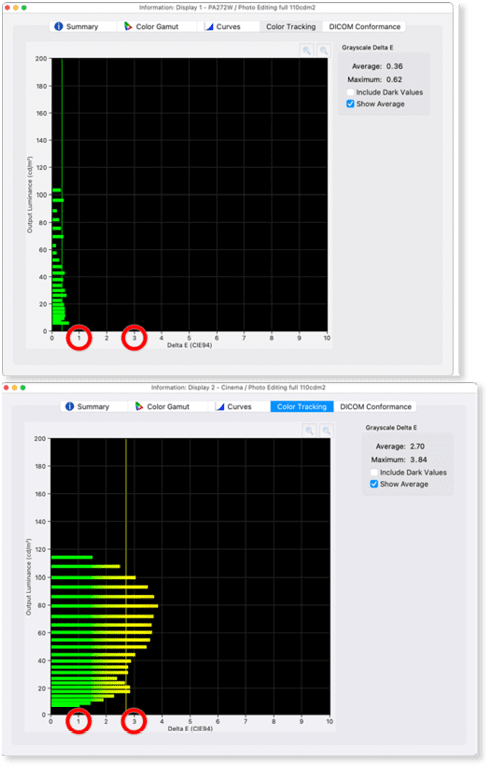

Display color accuracy is represented by a Delta E (?E) value, which describes how close the display is to the standard it was calibrated to. If the Delta E value is less than 3, the inaccuracy is so small most people won’t notice. If it’s less than 1, color professionals probably won’t notice. But if the Delta E value is greater than 3, consider replacing the display.

In Figure 6, I compare the grayscale Delta E values of my 10-year-old pro SpectraView color display to my 18-year-old Apple Cinema Display.

Figure 6. On top, the Information window in my display’s hardware calibration software (NEC SpectraView II) shows its Delta E values from light to dark after calibration, all well below 3. Below, my very old Apple Cinema Display shows Delta E values above 3, its accuracy clearly deteriorated after 18 years.

The SpectraView Delta E values are still less than 1 across the entire tonal range, which is great, so I’ll continue to edit on this display. But my Apple display shows Delta E values exceeding 3 across an important range of tones. That’s not acceptable for pro work, so I now use it only to show windows that aren’t color-critical, such as web pages, desktop windows, text chats, and tool panels.

Another reason to stop using a display is if its backlight has lost so much brightness that it can no longer reach your calibration target luminance value.

Uniformity: Consistency Across the Display

If the brightness and color balance are consistent across its surface, a display has great uniformity. Poor uniformity can be a problem if you color correct photos or video.

For example, if a display is noticeably darker in a certain spot, you might think a photo is too dark there, so you apply an edit that lightens that area. But the image wasn’t actually darker there, so when the image is seen on a display with better uniformity, the image now looks too light in that area: The display’s poor uniformity misled you into an unnecessary edit.

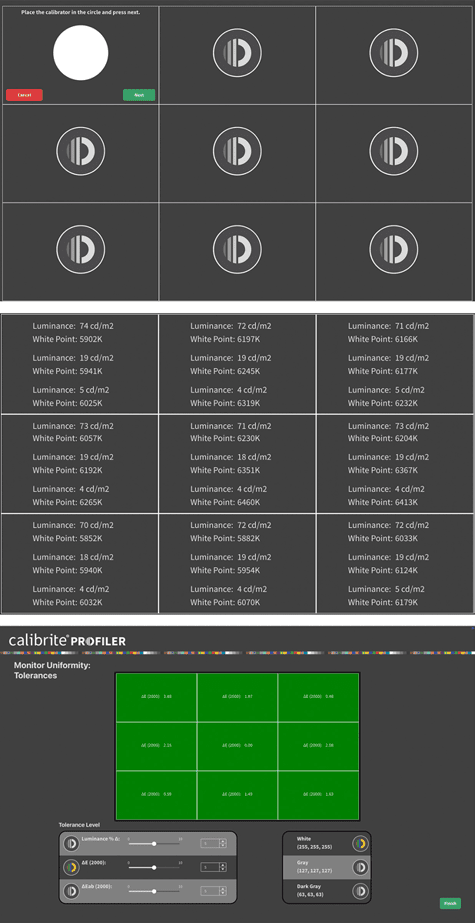

Uniformity isn’t part of a typical calibration, where the calibration sensor is placed at the center of the display. If uniformity is a concern, see if the calibration software you use has a uniformity test that leads you through placing the calibration sensor at different positions on the display and measuring the colors at each position. The test will reports on how uniform those values are (Figure 7). Perfect uniformity is rare, so expect some variation from corner to corner.

Figure 7. A uniformity test on a laptop display using Calibrite Profiler. From top to bottom: The software leads you through measuring a grid of nine positions on the screen with a calibration sensor, reports the measurements at each position, and shows that the screen is within an acceptable range of variation.

Go Forth and Calibrate

If color accuracy is a requirement for your work, invest in a color calibration device and recalibrate your displays regularly. Software calibration works well enough for most professional work. Step up to a display with hardware calibration if your clients have tight color requirements, or if you’d benefit from being able to easily switch among calibrations for different media delivery standards.

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

InDesign Magazine Issue 122: Cross-Media Color

We’re happy to announce that InDesign Magazine Issue #122 (June 2019) is no...

Before&After: How to Cool a Hot Photo

How do we cool this photo? The answer is found on the color wheel.

Using RGB Images in InDesign, from Photoshop to Final PDF

A step by step guide to entering the twenty-first century by using a RGB workflo...