Heavy Metal Madness: We, the Yearbook Nerds

Recently, a teacher friend of mine was recruited to become the yearbook advisor at a local high school next year, and he asked me for advice. While I think he means technical advice, like what the cool programs are or what I think of QuarkXpress vs. InDesign, I’ve fallen into a complete funk trying to think of what to say to him. Not because I’m uninterested in the subject of yearbook production, but because during my own high-school hell it was a yearbook advisor who saved me and profoundly influenced what I was to become. This is not advice to give lightly, and because my own memories of this period are so bittersweet, I wish my friend had been asked to be soccer coach or moderator of the French club. Then I could just make up my advice based on no actual experience, a practice I prefer.

On the “nerdy high-school activities” scale, working on the yearbook or student newspaper is nothing to be ashamed of — a clear acknowledgement that sports isn’t your thing, but not as pathetic as being in band or glee club. Publishing has always been glue that brings photographers, artists, writers, and business people together around a common enterprise, so it’s a perfect mini-life exercise for teenagers. There are deadlines to miss, lots of mistakes to be made, and great disappointments at the end when the book comes back from the printer. Perfect prep for a life in the graphic arts. And since to participate in the yearbook you don’t have to change into a uniform or have a ball of some sort thrown at you, yearbook was clearly the place for a skinny hippie-wannabe like me.

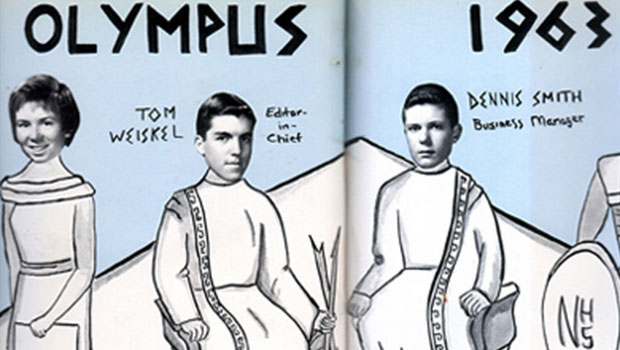

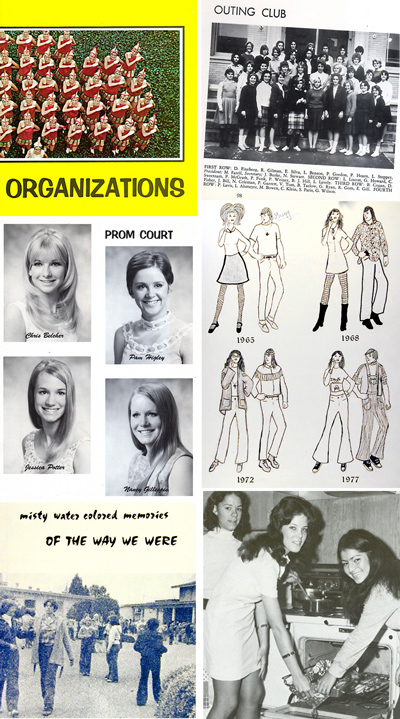

Yearbook nerds throughout the ages. In most high-school yearbooks, one of the biggest spreads is for the staff, who quite often fall into the “ham” category anyway.

I entered high school in 1970 under a bit of a cloud, which made me even more self-conscious than the other 100 Catholic boys that made up my freshman class. My older sister died from Leukemia the first week of classes, and because it was such a small school and tight religious community, that distinction became my identity: “the guy whose sister just died.” I felt an intense paranoia that everyone was looking at me all the time, so I took up photography and hid behind a camera and in a darkroom for four years. I highly recommend this hobby to adolescents — you can go to dances without a date, participate in sporting events without being humiliated, and I once got out of being thrown into a mud pit along with everyone else by keeping the camera firmly around my neck. The media, even in high school, is a privileged class.

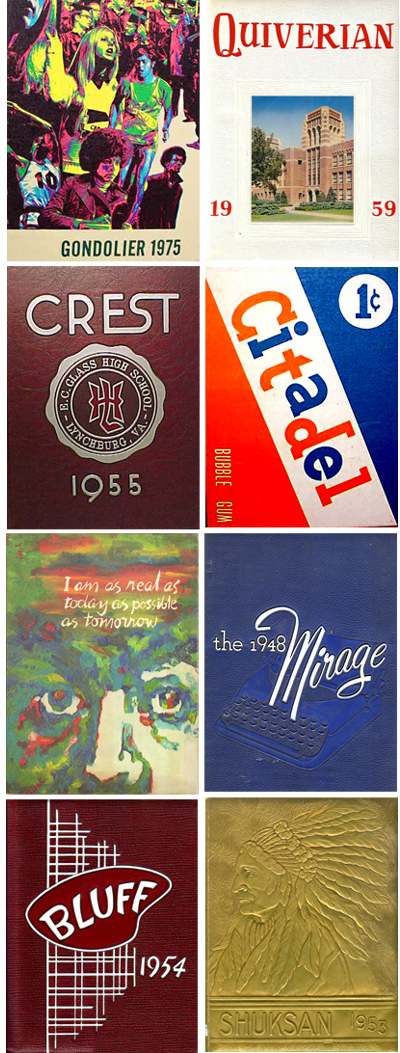

Yearbook cover art varied throughout the years based on technology in place at the time. From the very beginning, it was common to give yearbooks a name, though I’m not sure I would ever have christened one “The Bluff.”

A Record of Our Accomplishments

As early as the 1600s, there are records of hand-written keepsakes that chronicled the school year, though they are more comparable to scrapbooks than today’s yearbook. Students would save important papers, dried flowers, and snippets of hair, though we aren’t sure if anyone ever wrote “have a bitchin’ summer and don’t get too tan” in the margins. The term yearbook popped up in the 1700s, and most sources credit Yale University with the first American-published yearbook (more like a small photo album) in 1806.

Colleges were the first institutions to adopt the yearbook as a right of passage, but in 1845 the first high-school yearbook (The Evergreen) was published in Waterville, NY. Early yearbook printing technology meant that photographs and artwork were expensive, so these annuals served more as alumni directories and documented the accomplishments of students in list form rather than in the candid photo style we’ve come to love. Yearbooks were also much more likely to combine literary and art components in those early days, often with published fiction, poetry, and other efforts culled from the academic year gone by. As letterpress printing and halftone picture composition caught on toward the end of the 1800s, more schools jumped on board the yearbook bandwagon. Schools began to split up their publishing efforts, and many institutions produced both a yearbook and a literary magazine, freeing the yearbook to become more of a photographic chronicle of student life.

Even as early as 1921, the Petaluma High School Enterprise (above) was doing candid cartoons for the senior page, and the 1916 cover (below) of The Bell from San Jose High School. Color pages in yearbooks like these were often actual photographic prints glued on by hand.

Student artwork for headings and other incidentals ranged from very bad to very good. Here are a few better examples, from 1921, 1930, and 1946. Hand lettering was common in yearbooks up to the computer-set era.

Yearbook popularity reached a bit of a peak in the 1930s, as a combination of better production facilities and a rise in the hobby of photography swept the industry. By then several national companies had emerged to specialize in the process of producing and printing yearbooks, and stock packages of yearbook services were becoming available. Prior to this time, most yearbooks were printed by a local printing firm and composed like any other custom print job. Taylor Publishing in Texas first introduced offset printing to the industry in 1939, and the company’s “Taylor Plan” combined easy-to-use tools for yearbook staffs and delivered a start-to-finish composition “kit” still used in various forms by high-school students today.

The emergence of specialized yearbook printing companies like Taylor, Jostens, and American Yearbook fuelled the industry, and sales reps began visiting schools and selling them on the yearbook concept, offering easy start-up and cost-neutral publishing plans. Yearbooks have mostly been paid for by students, and in the ’30s the typical price per book was $6. Local advertising has been a staple in yearbooks since the Twenties, and is often the first introduction to business for future sales superstars.

Printing technology has always played a big role in yearbook quality. Several generations of the Taylor family (above) pioneered new printing and composition technology at their Texas plants, which they continue operating today. Below are several of the forms high-school yearbook editors become familiar with before the end of the year-these from publisher Herff-Jones.

Paper and resource shortages during World War II resulted in many schools eliminating yearbooks, and annuals didn’t make a big comeback until the baby boomers began their “it’s all about me” life cycles in the ’50s and ’60s. The popularity of picture magazines like Life and Look certainly contributed to a move in yearbook style away from rigid small photos of students to double-page spreads showcasing larger and more candid photographs.

During the ’70s and ’80s, odd-size and unique yearbook configurations became popular, and schools started experimenting with multi-media products. Yearbook companies became more competitive in their offerings, and yearbook printers consolidated. Many of them were technical innovators thanks to their deadline and cyclical-intense production cycles. Taylor, for example was electronically paginating all of its yearbooks back in 1975 on a custom-designed system called Cybercomp. Technical advantage was the upper hand in a highly competitive segment of the printing industry.

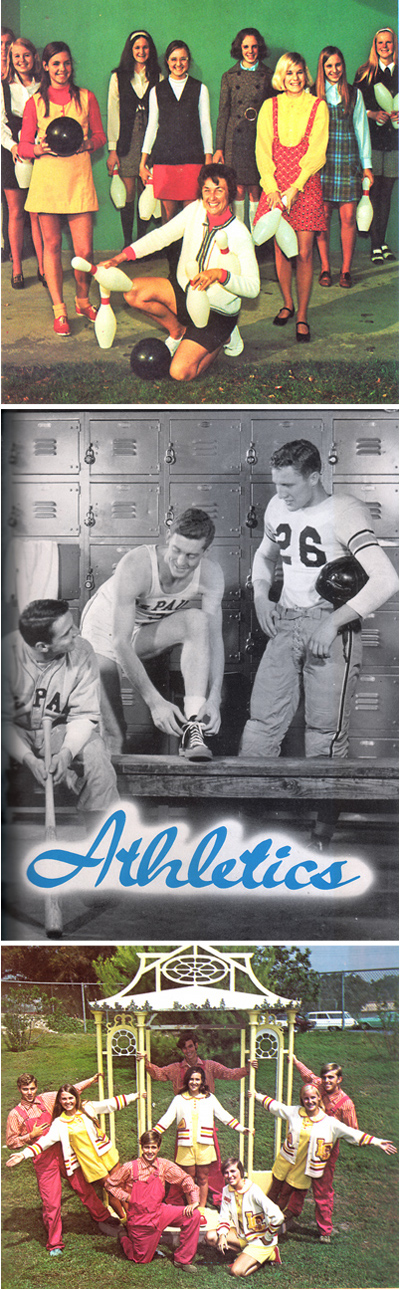

Smells like teen spirit. Yearbooks and sports go hand in hand. Above and below, two colorful snaps from the 1969 La Canada High Omega, and in the middle, an intro page from the 1948 DePauw University Mirage.

Deadlines Make for Good Friends

My own yearbook advisor was an English teacher named Kathryn Konoske, who also taught journalism and probably several other subjects. Her willingness to be the yearbook moderator may have been primarily because she could take smoking breaks in the yearbook office, but you’d never know it from her enthusiasm. She’d hold court, chain smoking between classes or during breaks, telling us stories and teaching us the standards of good journalism and design. Occasionally she’d allow an editor to light up — it was our little secret, and we were the only ones with keys to the office.

I learned from Mrs. Konoske how to crop a photo using a Scale-O-Graph, though the emphasis with her was always the subject, not the technology (as crude as it was). She taught me how to see the “flow” of a spread and pay attention to details like which direction the picture subjects were looking. “Follow their eyes,” she’d say. “That’s where people will be looking next. Make sure there is something for them to see.”

Publishing is serious business, too, as these ads demonstrate. When businesses were mostly local, ads were often staged shots of students frequenting the advertiser’s place of business.

Like so many yearbook staffs in the ’70s (and throughout time), we wanted to do something “really unique” our senior year. KK (the nickname we had given her) not only encouraged us but also took care of all the approvals and finances necessary to create a yearbook that didn’t fit into the normal production flow at American Yearbook (which had just been purchased by Jostens in one of the first big industry consolidations). She took us on a three-day trip to Fresno so we could tour the printing and composition plant, an experience that made a big impact on me. Mrs. Konoske knew that understanding what happened to our work after we mailed it to the plant in those pre-printed manila envelopes was an important part of the creative process.

When our long-time sales representative from American died suddenly from a heart attack, the victim of too many cafeteria lunches and high-school staircases, KK cried openly, and while it made many of the other boys uncomfortable, it opened the door between her and I to talk about my sister — the first adult I had done that with. Her wisdom of life seemed expansive, and she always treated us like adults, never once letting on that she had done this all before one too many times. To her, journalism and publishing were the highest calling. We had a responsibility to push our creative efforts on behalf of our readers, and to rise above petty high-school stuff and act like professionals.

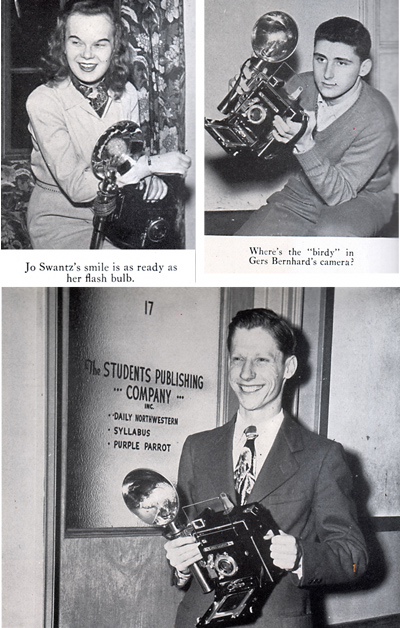

Yearbook photographers may be among the nerdiest high-school species. Here, three contributors to the 1947 Northwestern Syllabus.

At some schools yearbook is a class activity, done in the structure of a daily or weekly academic activity. For us yearbook was purely extra-curricular, and so the normal structures of school were broken down a bit and we learned the important lessons of collaboration, patience, and envy. The slackers get weeded out quickly, and when everything clicks you learn how to tap into the talents of each individual without compromising for the sake of ego.

By the 1930s, high-school yearbooks were much more than just listings of students, and reflect the sometimes odd priorities of the times. An Outing Club, by the way, was a 1969 group of women who sold candy at basketball games.

Being Mistaken for an Adult

If they’re lucky, the most important thing kids learn from working on a yearbook is not how to use white space appropriately, or how to avoid rivers in a two-page spread, but rather how to work collaboratively and with dignity. I completely failed that lesson, which is why I find it so hard to give advice to my yearbook-advisor friend.

Despite several years of support and mentoring, when it came to the end, I found a way to hurt my yearbook moderator’s feelings by writing something immature and hurtful about her in another student’s yearbook. I was in the room when she read it, paralyzed, holding my head down while she fought back tears. Fortunately it was the last week or two of school, so the fact that we didn’t speak again was painful only for a short while. She had treated us like men, and I acted like a little boy.

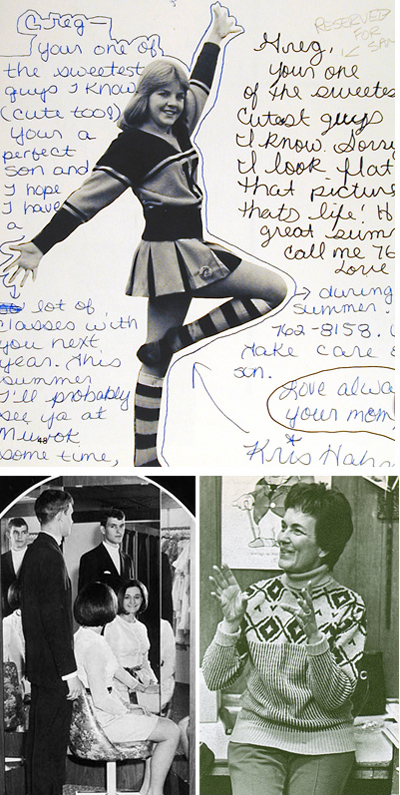

It was not until after World War II that students began the practice of inscribing yearbooks, thus getting themselves into trouble by saying too much or not enough. Up until that time, most people simply signed under their picture. Here, a boy named Gregg was popular when he attended Kenilworth Jr. High in 1977 (above), a “most attractive” couple is pictured from 1969 (bottom left), and my own high-school yearbook moderator Kathryn Konoske (bottom right).

Years later I wrote a letter to Kathryn Konoske, telling her of my accomplishments and thanking her for being such a positive influence in my life. I didn’t get an answer. For all I know she was no longer teaching, and I didn’t actually come out and apologize, so I’m not sure I deserved an answer. Maybe she didn’t even remember me.

Lots of kids have important revelations in high school, and plenty of them make mistakes that lead to hurt feelings. For me, working on the yearbook was salvation, and it gave me purpose and confidence in a world where I did not otherwise fit. It taught me the basics of page-layout and design, but most importantly it taught me that words, particularly when they are not well thought out, are still the most powerful tool in the publisher’s arsenal.

I think I’ll pass along the following advice to my teacher friend:

- Avoid trapped white space.

- Don’t have people looking off the page.

- Give every spread an obvious focal point.

- Don’t overuse special effects.

- Keep your distance with the students.

Read more by Gene Gable.

This article was last modified on March 2, 2021

This article was first published on June 2, 2005

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

The Case of the Imperfect Paste Contest Answer and Winner

The solution to our latest InDesign mystery revealed.

Kapitza Shop Releases Free Animal Outline Font "Creature"

KAPITZA SHOP, a new online shop specialising in picture fonts and illustrations,...

TypeTalk: Stroking Text in QuarkXPress

TypeTalk is a regular blog on typography. Post your questions and comments by cl...