Heavy Metal Madness: I'm Looking Through You. Where Did You Go?

In its heyday, Kodak sold over 300,000 slide projectors a year. By 2003 that number had dwindled to less than 20,000, and the decline was rapid enough for Kodak to get out of the business entirely. Slide shows are considered campy these days, replaced by PowerPoint presentations and digital projectors, which are still just as boring, only now you can’t fall asleep as easily because the lights don’t have to be dimmed as much.

Graphic artists have always known that color photographs seem to reproduce better from transparencies than prints, and I suspect most will now confess that digital images are even more accurate and certainly easier to deal with. The new camera raw format takes the limits of the equipment out of the equation even more, and though we can certainly re-create the flaws that made a Kodachrome image so great, those images will never look quite the same without a bright light passing through the film’s emulsion and up to the screen or living room wall. Part of the memory of slide shows gone by is that of cigarette smoke or dust particles dancing in the projector’s beam.

You can still find plenty of Kodak Carousel and Ektagraphic projectors on eBay and at garage sales, right alongside the Salton yogurt makers and (more recently) George Foreman Grills. I still have several myself. But honesty requires that I admit I haven’t dragged out those projectors in years, and I much prefer to fire up the slideshow feature of iPhoto. We are willing to give up quite a bit in the quest for convenience, so I can’t place any blame on Kodak. I was actually surprised to discover they could still sell almost 20,000 projectors (probably all replacements) a year. But I strongly reserve the right to act indignant at the news of the slide projector’s death.

Your Lips are Moving. I Cannot Hear

George Eastman, the founder of Kodak, died in 1932, the same year the company introduced the first 8mm home-movie camera and film. For the next fifty years, some form of 8mm movie film recorded the silent lives of millions of children and adults, and the ritual of setting up a projector and screen was either much anticipated or much feared. For the first few years these records were limited to black and white, but with the release of Kodachrome movie film in 1936, memories came in vivid colors, as well.

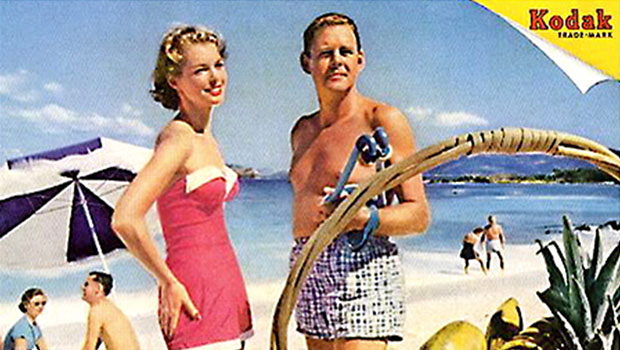

Kodak introduced home-movie cameras and projectors as early as 1923 (when this ad appeared), but they were the larger 16mm format. It wasn’t until Kodachrome and the 8mm film format hit the market that home movie-making really took off.

Two images from the Kodak publication “How to Make Good Movies.” Above, movie viewers are clearly impressed and filmmakers satisfied (and not completely surprised) by the special effects described in the book. And while very few people had media rooms in those days, some, like Mrs. R.C. Surridge of Baltimore, Maryland, had home theater set-ups nonetheless (below).

My dad was quite the movie buff, so we endured our share of standing at rigid attention while facing directly into the sun as he panned back and forth, recording us much like you would if documenting our existence for an insurance company. Of course we stood in age order, which, fortunately, was also size order. By the time I eclipsed my sister’s in height, my dad had lost interest in home movies, so we never had to make the difficult choice between lining up chronologically or by size.

I don’t remember watching movies on Christmas night, but I take it on faith that many families did. Instead, we used Christmas as a filming opportunity and an excuse to break out the high-intensity movie lights. It was hard to show the proper enthusiasm when opening a gift, however, due to the temporary blindness.

The relatively low speed of Kodachrome (ASA 25 for most of its life) assured that home movies either took place in the bright noonday sun or with the aid of a blinding set of photo-flood lamps that were powerful enough to land an aircraft. The arrival of Santa is hardly a spontaneous moment for a five-year-old when he is temporarily blinded and the adults are all shouting to either look at Santa, look at the camera, or look “natural.” It’s no surprise so many home movies turned out to document a small child’s crying jag, which, on subsequent viewings seemed to be amusing to the adults.

Unlike video, which can be easily rewound and recorded over, movie film was unforgiving. Getting Junior to look at the camera and do something cute was no small feat, and a half a roll of unusable footage was not uncommon. Editing home movies is a story in itself and somewhat comparable to paste-up, only with really toxic glue and at a much smaller scale.

My favorite part of the home-movie era, of course, was setting up the projector and screen, which in most houses lived in a rarely used closet alongside the folding card table and Carrom board (if you were lucky). Home-movie screens were designed like props from an episode of “I Love Lucy” or the Pink Panther movies — it was easy to get either hurt by them or have them spectacularly collapse mid-way through the show. And even with a really bright bulb in the projector paired with a Day-Lite glass-beaded screen, the luminosity of your average home movie was pretty grim.

Part of the fun of home movies (which is lost with video recording) was the delay between shooting and viewing. Sometimes a roll of film would sit in a camera for months or even years before being processed. Projecting the results for the first time was always a surprise, and it was considered a win if the exposure was even close to correct. Threading 8mm film through the camera and the projector was tricky and often lead to bizarre mis-feeds that sent Dad running to the projector and Mom running to the light switch.

I don’t know if people have “video parties” these days, but sitting through someone’s home movies after dinner was a common occurrence and often led to embarrassing moments when guests were caught sleeping. The cartoon (above) is from a 1968 ad for Bauer cameras, which were guaranteed to make your home movies more exciting. It’s not clear if pictures of your kids tossing a beach ball (below) would keep the guests awake.

But 8mm home movies elevated everyone into the big leagues of motion pictures, and you could ham it up all you wanted, get pretty deep into things like titles and fancy transitions, and if you were my father, you could slow down the most humiliating scenes to a painful crawl. Or run the projector backwards for some real laughs.

The popularity of home movies hit a peak in the 1960s as 8mm automatic exposure cameras became more common. Here are examples of both Honeywell and Bell and Howell targeting women in their 1964 advertising. A year later, in 1965, Kodak introduced Super 8 Kodachrome film, which came in handy cartridges and boosted image size by almost 50% over standard 8mm film.

8mm movies grew up, I think, when the Kodachrome Zapruder film of the Kennedy assassination was finally released several years after his death. There, in the same colors that defined our childhoods, our important milestones, and the good times of our lives, were images of someone getting his head blown apart in front of his terrified wife. If you can imagine, Time/Life bought the film so it could not be shown, and it was reasonable at that time that such horrifying images would never be broadcast. When it did finally air, that two minutes of Kodachrome signaled the beginning of a world where everything, good and bad, is recorded in living color and available to view should you have the stomach for it.

Two images from the terrific book Kodachrome, the American Invention of our World by Els Rijper. Above is an International News staff photograph of Jane Withers and friends at a Halloween party, 1946. Below, a 1953 picture of Senator John Kennedy and his fiancée Jacqueline Bouvier. Kodachrome certainly contributed to the Camelot image of the Kennedy era, but it also signaled the end of it when Abraham Zapruder used 8 mm Kodachrome movie film to capture his famous footage of the young president’s assassination.

You Don’t Look Different, But You Have Changed

I can’t tell you exactly what it is about Kodachrome images that I’ll miss. It could be the film, it could be the reproduction methods that paralleled the product’s popularity, or it could be that I simply prefer to look back more than forward. And it may be that my memories of the mechanical things, like threading the 8mm film through the projector, or remembering to place the slides in the trays upside down and emulsion out (or was it in?), have tainted my recollections.

But color plays an important role in my memories — right up there with smell and taste. All of those senses become clouded over time, I know, and our memories are romanticized. When I eat a Zagnut candy bar as an adult, it seems way too sweet and brings little of the pleasure it did when I was seven. And so it should go with old pictures and home movies. But for some reason, the opposite happens. I end up preferring the extra-sweet version of life to the one I know to be true.

Thank you, Leopold Godowsky, Jr., and Leopold Mannes, for providing the color palette for my life. When I think of a visit from Santa or see myself in a cap and gown or at a birthday picnic, it’s through your considerable filter.

And thank you, God, for getting me through this entire column without making any references to Paul Simon’s song.

Read more by Gene Gable.

This article was last modified on May 19, 2023

This article was first published on July 27, 2005

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Sometimes a Logo Is Just a Logo

The Legal Ramifications According to a trademark attorney I spoke to, trademark...

How to Extract Images with Hair Using Photoshop’s Refine Mask

The following is an excerpt from Speaking Photoshop CS6 by Dave Bate. You can al...

How to Permanently Delete Cropped Data in a PDF

Have you ever tried to crop a PDF file, cutting out part of a page? It’s pretty...