Heavy Metal Madness: Confronting Setbacks Honestly and with Grace

2. Over-Estimating Your Abilities. This second category of setback is the one I hate the most, because it usually involves my wife saying “I told you so,” though she doesn’t actually have to say the words any more — it’s simply understood. I once fried a friend’s rare cactus plants when I volunteered to wire the heated soil device in her greenhouse and hooked it up to 220 instead of 110 volts. (I was really careful with the cat’s beds, I swear.) And I’m certain I’ve broken more things than I’ve fixed in my time, but it doesn’t stop me from trying again and again, usually justified by wanting to save money or time. I think I inherited this trait from my father (see Figure 3), who almost always over-tightened screws and nuts to the point of shearing them off and causing undo amount of extra work when the job should have been done. “I’ll just give it one more turn for good measure,” he’d say, and I’d grimace and step back a few feet to avoid the flying shrapnel that invariably followed.

Figure 3: Like father, like son. My dad taught me not to fear things like electricity, power tools, and motors, but he also passed on his knack for over-tightening screws and nuts.

Into this category falls the biggest setback so far — a forklift accident during shop move in that I’ve been in denial over for months. I had never driven a forklift, never been on a forklift, and certainly never used a forklift to move highly unbalanced cast-iron equipment (in the pouring rain) before. But I paid to rent the forklift, dammit, so I figured I should be the one to drive it. Anyway, none of the cats were forklift rated either, so it came down to me regardless.

I should have known there was potential for trouble when the rental yard required I sign a waiver and a document saying I was “licensed” to operate such a device. I admit I lied, but then I’ve seen forklift operators at Home Depot and it looks pretty easy, so I figured it was a formality. Besides, things started off great, and I was having lots of fun playing like a construction guy (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: The forklift experience started out fun enough, but soon turned dark when I stepped on the gas too hard and dumped one of the presses on its side.

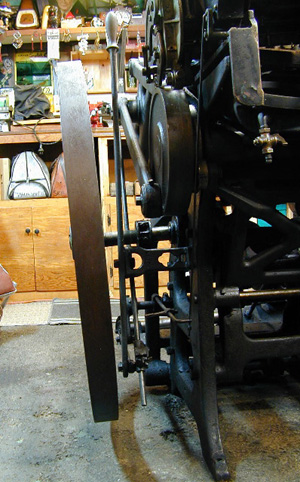

Luckily when I dumped the Chandler & Price platen press on its side, I didn’t kill anyone, and the cats had the good sense to disappear the minute they saw me turn the ignition key. But I did bend the press’s main drive shaft (see Figure 5) and broke several pieces that will need welding/and or straightening. And I put a pretty big hole in the asphalt floor. That one moment of stupidity will end up costing me more time and money than if I had hired a trained professional to do the job.

Figure 5: The wheel on the Chandler & Price platen press should be straight, had it not fallen off the forklift and dented the asphalt floor of my shop. Sadly, the asphalt wasn’t soft enough to prevent damage.

I also had a minor incident which I could blame on God (who made gravity, after all), but I really have to blame it on myself for over-stacking a bunch of 50-pound Intertype font magazines (see Figure 6) on a cheap Ikea TV stand that we no longer used. Particleboard, for those of you unfamiliar with it, is really just thick cardboard, and cannot, despite its attractive Melamine finish, hold several hundred pounds of dead weight. But this collapse merely created a mess, and didn’t seem to do any real damage, except to my ego.

Figure 6: A magazine for the Intertype, which holds a complete font of matrices for lead casting and weighs at least 50 pounds. I piled 8 of them on an Ikea TV stand in an experiment to test the strength of particle board.

3. Underestimating the Complexity of the Job. This third category of setback is the most common, and the one I fall victim to over and over again. This is what happens when you decide to learn Acrobat 6 the night before a big job is due to the printer, or you tell your customer you can drop that background out in Photoshop no problemo, and substitute a beautiful sunset in its place.

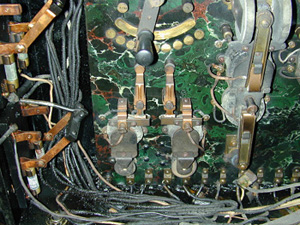

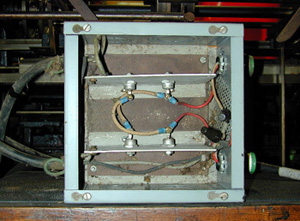

Into this category falls the electrical work I’ve taken on trying to get my equipment up and running. I won’t bore you with the details, but each machine has some sort of special requirement, the most novel being the ATF Kelly press that runs off of 220 volts DC, which for you non-electricians is like saying it runs on hydrogen or nuclear fission — not any easy voltage to produce in your typical 1950s garage. I’ve tracked down a voltage converter (see Figure 7) but I don’t know if it works and I certainly don’t have a clue how it functions, so troubleshooting will be tough.

Figure 7: The ATF Kelly press has a wild electrical system mounted on green marble (above), and requires the mystery power converter (below), which turns alternating current (AC) into direct current (DC).

And of course I’ll be pushing the limits of our home’s 200-amp electrical service — a little like what happens to the Enterprise when Kirk orders Scotty to crank her up to Warp 11 — she may blow at any moment. I’ll have to warn Patty not to use the microwave when the typesetter is going, and the cats will probably have to suffer cold beds once things are up and running. Or, I could break down and call an electrician, but then in my book that would cheating, and might end up saving both time and money.

I also discovered that lubricating and cleaning all this stuff is overwhelming — there’s so much rust, frozen gears, and caked grease, that it sometimes feels hopeless. So I’m tempted to set a real deadline, which is usually what prompts me to finish up and move on. Sometimes we have to lower our standards and be satisfied we’ve done the best we can, though my goal was to have all the machines looking shiny and new. I’m starting to get requests for shop visits, and it’s embarrassing that nothing is actually running yet.

Always Come Clean in the End

Most times we figure out a way to pull things off regardless of our setbacks, and I will tackle each one of mine the best I can. After all, the process is part of the adventure, even if most of the external focus is on the finished product. And the one good thing about coming clean and admitting that not everything is going smoothly, is that it frees you to focus on solutions instead of lies, cover-ups and deception.

And of course, once you drop an antique printing press off a forklift, or spread black napalm all over your person and property, or even allow your poor cat to become the laughing stock of the workplace, you probably won’t do those things again. And how else can you learn to appreciate the talents of the heavy-equipment operator, the cat groomer and the roofer?

I have more than a few cuts and bruises to show for my work in the shop so far, and the pain of having to admit these setbacks is excruciating. What worries me most, however, is that I think I’m beginning to enjoy it.

Read more by Gene Gable.

This article was last modified on May 19, 2023

This article was first published on May 1, 2003

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

PDFpen 3.3 Released With Enhanced Annotation Display

SmileOnMyMac has released PDFpen 3.3, its PDF editing and form-filling tool for...

Review: Crazy Talk 8

CrazyTalk 8 by Reallusion is an application that brings photographs to life, ena...

Quark Names Raymond Schiavone President and CEO

Quark Inc. today announced that Raymond Schiavone, a veteran software company CE...