Eye On the Web: How Navigator Could Win the Browser War

Remember 1998? Those heady days of judicial drama when the long-gone informal alliance of rebel technology companies, behemoths Sun Microsystems and Netscape among them, dragged the federal government into battle against that even bigger behemoth Microsoft? The charge, as we will all recall, was that Microsoft had engaged in anti-competitive business practices by tying its browser, Internet Explorer, to Windows. And Windows, as we all recall, had a pretty clear monopoly on the operating system market at the time.

I was all for the federal suit. Down with Microsoft, I thought, and up with the little guys (or at least the not-as-big guys). For years, any remotely innovative software product was either elbowed out of the market by a decidedly inferior clone from Microsoft, or else the Redmond giant simply bought up its parent company and adopted that software as its own. Either way, we were increasingly living in a Bill Gates-dominated world and I didn’t like it.

But then Netscape, Microsoft’s most vocal rival and certainly a catalyst behind the anti-trust suit, was swallowed itself by another behemoth, one that no one had counted on to enter the technology market in such a way. America Online (AOL), after all, was a service company, a very large service company. And now, with its acquisition of Time Warner, a company whose strengths lay in marketing and branding, AOL is a media company, avery large media company. What was AOL going to do with Navigator, the only browser that was competing (although with less effectiveness) against the Internet Explorer steamroller?

A Little Marketing Goes a Long Way

Well, last week we found out. With the release of a preview version of Netscape Navigator 6.0, coupled with the long-awaited federal ruling against Microsoft, AOL proved that marketing smarts go a long way. Its new browser hinted that the grace of good marketing plus a dose of technology, and not the government, may be the downfall of Microsoft’s browser monopoly.

Until now Microsoft has claimed, rightfully, that its browser complies with more Web standards (those pesky technologies agreed upon by committee at the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) which ensure that any Web page will look the same in any browser window) than any other on the market, meaning Navigator. And this week, in answer to the Navigator announcement, Microsoft is vying to keep that title by releasing a preview version of IE 5.5. The update promises support for even more standards, including a multimedia technology called HTML+TIME, Microsoft’s answer to SMIL (synchronized multimedia integration language), a technology already ratified b the W3C.

Of course Microsoft’s standards dominance only holds true for the Windows version of IE. The Macintosh version, built by a completely separate development team, didn’t adhere to the same standards until Version 5.0 was delivered in March. Following that trend, there is no word on when IE 5.5 for the Mac will debut. Apparently Microsoft’s marketing honchos feel Mac users are less interested in technology than in usability (the previous Mac version of IE added features aimed at convenience rather than standards-compliance). Which all makes sense, since we do all use those funny fruit-colored computers.

All Things Come to Those Who Wait

Navigator 6.0, based on a spanking new layout engine called Gecko (a name that recalls the fluorescent-colored gear donned by many a Silicon Valley roller blader), promises to be just as standards compliant as the latest Internet Explorer releases, now at version 5.0 for both Windows and Mac machines. But Navigator has a number of advantages, most of them in the sphere of marketing that AOL knows so well.

Firstly, Navigator 6.0 is being released simultaneously on Windows, the Mac OS, and, boldly, on Linux. That Netscape, and AOL, are embracing this upstart operating system, and potential threat to Windows’ dominance, is commendable and, well, wise.

Secondly, Netscape skipped entirely over Version 5.0, which the browser-watchers among us have been patiently awaiting for at least a year. Netscape’s, and AOL’s, explanation is that Version 5.0 was based on the old layout engine and since it took them so long to get that version together they eventually had to scrap it in favor of a browser based on the new Gecko layout engine. Hence 5.0 went out the back door and 6.0 came to be. Pretty dubious logic, if you ask me, but the 6.0 tag does give Navigator an advantage over Internet Explorer 5.5: since it is a higher version number, it has the aura of being more advanced, of adhering to more innovative technologies. An example of the AOL marketing geniuses at work.

Thirdly, Navigator 6.0 portends to include input from mozilla.org, Netscape’s open source browser project. About a year ago, the company set up a Web site where developers could download the browser’s source code, make changes to it, and share ideas. By incorporating these ideas, Netscape does more than just get free advice from developers: it positions Navigator, once again, as the people’s browser.

It’s ironic that Navigator, which first railed against Microsoft as a bully with an unfair advantage over the little guy, is finally in a position to beat that bully at its own game. If Netscape wins the browser war (which may well end in a stalemate anyway), it won’t be because the government prevailed on the side of the righteous, like I always hoped it would. It will be because Netscape, like so many technology companies before it, got itself bought by a big gun, one that also has the power to paste it across the desktops of its trillions of customers, one that has a firm handle on the power of branding, one that has an almost frightening hold over us, the consumers.

Andrea Dudrow is a writer living in sunny San Francisco. She has been covering the Web and Web design for the past four years and has contributed to Macworld, MacWEEK, eMediaweekly, Adobe.com, Adobe magazine, Publish, and the San Francisco Chronicle, among others. She also writes about arts and culture, and spends a great deal of time fantasizing about the broadband future.

This article was last modified on January 6, 2023

This article was first published on April 10, 2000

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

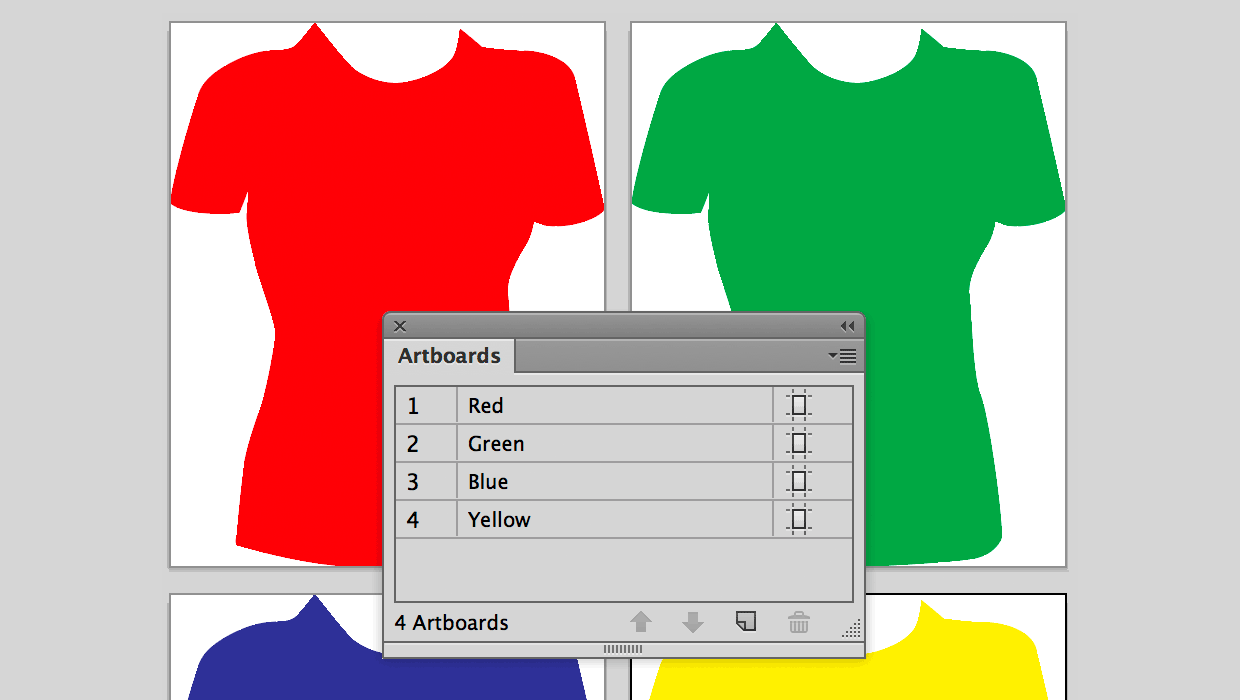

Using Illustrator Artboards to Place Versioned Content in InDesign

A useful alternative to using Illustrator layers and layer overrides in InDesign...

InDesign Basics: Working With Layers

InDesign Basics is a series of articles for new InDesign users, highlightin...

5 Freelancing Mistakes to Avoid

Freelancing can be a source of freedom or overwhelming anxiety depending on situ...