Charting the Way to a Successful Digital Workflow

Cartography has always been a forgotten stepchild in the world of design. Though maps certainly require a great deal of design skill, few designers would trade in their work on print ads and corporate identities to build maps of northwest Washington State or Lake Erie, no matter how beautiful.

Lawrence Andreas feels differently. As a cartographer with Allen Cartography and its partner company Raven Maps & Images, both located in Medford, Oregon, Andreas creates maps and oversees eight cartographers as they churn out the equivalent of one map per day. Raven Maps makes high-quality atlas maps as well as those beautiful laminated wall maps you’ll find pinned up on the walls of university lecture halls or hung up in the cubicles of co-workers who harbor an unusual fondness for a particular geographical region.

Raven Maps moved to an all-digital workflow two years ago to create its high-quality wall maps.

“It’s unbelievable the amount of detail and forethought that goes into a quality map,” said Andreas.

Andreas should know. He’s been designing maps since the advent of desktop computers, and he helped Raven Maps make the transition to a fully digital Postscript workflow two years ago. “When I started, we had one Mac and 10 light tables. Today we have one light table and 10 Macs,” said Andreas.

Connecting the Dots

Mapmaking holds special challenges, the foremost being the conversion of raw geographical data into a visual representation. For maps of locations within the United States, Raven Maps receives geographical information from the United States Geological Survey in vector format. “It’s just a series of XY points, representing longitude and latitude, or if elevation is included, then it’s a series of XYZ points, with Z representing the elevation,” said Andreas.

Andreas’ first job is to crunch the numbers and turn this matrix of information into a rough graphical representation. And he does so with a bevy of Graphical Information System (GIS) software programs, such as ArcInfo from ESRI, Vertical Mapper from Insight GIS, Idrisi from Clark Labs, and other programs running on the lone PC on the company’s AppleTalk network (the majority of GIS programs are available for the PC only).

Building Relief

Once the rough draft is assembled, Andreas and his team refine the image with two software programs familiar to most designers — Photoshop and FreeHand.

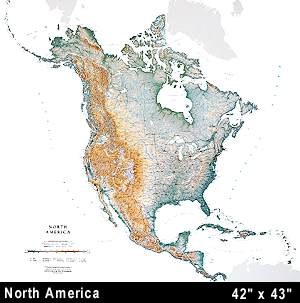

Raven’s United States wall map, which measures 37 by 58 inches. Color indicates elevation.

Photoshop helps Andreas assemble an intermediate image, first by creating relief shading with predetermined gray scales assigned to specific points in space to accentuate the direction of a slope and its steepness.

The next step is to assign color based on elevation. The colors progress from greens at lower elevations, through yellows and browns, to gray, and finally to white at the highest altitudes in the mountainous states. This sequence of color steps replaces the abstraction of contour lines with a graphic picture of elevation, resulting in a startling three-dimensional look, even though the maps are two-dimensional.

As shown in this “actual size” detail of the Raven’s U.S. map, the company’s maps take on a 3-D look through their skillful use of color to reflect elevation.

“The real trick is to combine the 256-grayscale shading with 24-bit elevation color. Not many companies have figured out very well how to take the digital elevation models and turn them into nice maps. It’s still a bit of an art,” said Andreas.

Next the map is imported into FreeHand where the final touches are applied.

“It seems art directors and designers prefer the freeform capabilities of Illustrator, but for our work we feel FreeHand is more rigorous, particularly the way it handles type styles and line styles in numerous layers,” Andreas said.

It’s here that Andreas and his team spend the most time creating that distinctive “Raven Maps” look. And though staff cartographers use many of the features provided by FreeHand, they still do much manually, such as trapping, do to the exacting nature of the work. “We build trapping for the eye, not for the algorithms that fit color theory.”

This article was last modified on December 14, 2022

This article was first published on August 3, 2000

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

How to Align Objects in InDesign Using Object Styles

Learn how to position objects on the InDesign page with efficiency and precision...

30 Years of Images with Louis Fishauf: A CreativePro Conversation

David Blatner chats with veteran visual communicator Louis Fishauf as they look...

Scanning Around With Gene: Let's Have a Tupperware Party!

I’ve never been to a Tupperware party, though I was once given a Shaklee v...