Scanning Around with Gene: When I Grow Up to Be a Man

When I was growing up in Southern California, I knew at a pretty early age what it meant to be an adult. Each day on page two of the Los Angeles Times, there were brief news wrap-ups for local communities and the state. Invariably, these items tended toward the violent, reporting on crimes, accidents, and the other consequences of urban living. And as was the style at the Times, males 17 or younger were referred to as “youths,” and those 18 or older as “men.” It was clear and simple. “A 10-year-old youth” drowned while on a scouting trip, or a “17-year-old Pasadena youth” was disfigured in a freak trampoline accident. Somehow all the tragedies of page two seemed even more tragic when they befell a “youth.”

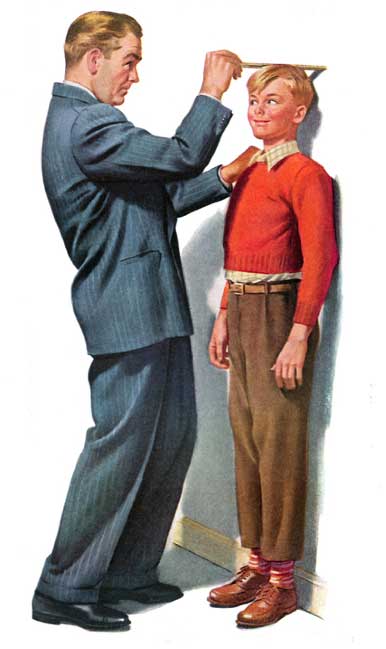

Figure 1: In 1943 this ad ran in Forbes Magazine, promoting the benefits of eating sugar to hasten growth. We know better now, but part of growing to be a man is actually growing to be a man.

The “men,” on the other hand, were almost generic. You could be “an 85-year-old-man” who had a stroke and plowed into a coffee-shop window, or an “18-year-old man” decapitated in a construction accident. No difference. To my youthful mind, reaching your eighteenth birthday simply meant fewer people would feel sorry for you when you tragically died. So I dreaded that day and secretly hoped my time would come while still a “youth.”

Figure 2: In some cultures manhood begins when a young man first has to fight for his honor or survival. This cover from Manhood magazine is typical of the 1940s image of real men.

Journalistic style aside, not much actually changed on my eighteenth birthday, and that seems to be the case for most kids. Recent studies indicate that adolescence can now last until about age 30, regardless of what local laws or customs dictate. And while many parents encourage independent living, the majority of financial, if not emotional, support now accumulates after the age of 18, not before.

But for some kids, such as my nephew Marc, turning 18 represents freedom from the control of adults, especially those who may have abused their responsibilities and hastened an unfortunate childhood. So instead of a gradual transition from youth to adulthood, they make the transition overnight, ready or not. This rarely goes well, and watching it can be difficult.

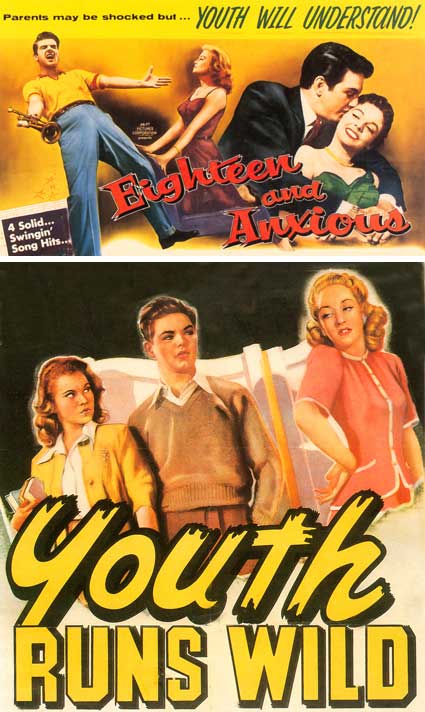

Figure 3: Teens out of control was, and still is, a popular movie theme. Here, two films warn of the gap between teen enthusiasm and adult responsibility. Above, from Republic in 1957 is “Eighteen and Anxious.” Bottom is the 1944 RKO picture “Youth Runs Wild.”

Will I Dig the Same Things That Turn Me On As a Kid?

Figure 4: The subheads in this column are lyrics from the Beach Boys’ hit single “When I Grow Up to Be a Man,” though some would argue the group did not set the best example themselves.

Marc came into our lives at age 14 with enough baggage to excite several therapists. It set off a quest on my part to take on the unfairness of the world, regardless of the folly. I quickly lost perspective, and my career suffered, my professional relationships floundered, my family ties became strained, and I almost lost the person most important to me.

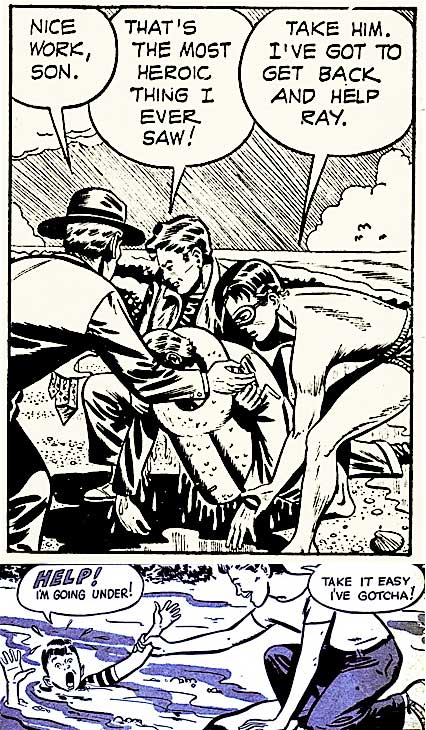

Figure 5: These two images from Boy’s Life Magazine express my feelings when Marc first came to live with us. I wanted to save him and be the hero. If only I had stuck with Scouting and not dropped out after the first year, I may have learned that lifesaving is first about taking care of yourself, then helping others.

Fortunately we saw the light and found a situation that assured Marc’s safety and our sanity in the form of a school in Montana. Things were going reasonably well, and this December, my wife Patty and I flew to Montana as a surprise for Marc’s eighteenth birthday. We were excited to greet him as an adult. On arrival we discovered that Marc had exercised his new adult rights by dropping out of school and embarking on an ill-determined path of independence.

Figure 6: When this ad ran in Hot Rod Magazine in 1967, it was estimated that a high-school dropout earned $100,000 less in his lifetime. Now, of course, $100,000 doesn’t even cover the tuition.

Will I Look Back and Say That I Wish I Hadn’t Done What I Did?

All of that leads to today, where I find myself in the uncomfortable position of giving Marc advice about manhood while holding him accountable for his actions. He’s even less ready to be an adult than I was at age 18, yet there he is, on his own without any means of support, and without a family to come home to. He continues to make poor choices and despite my natural tendencies to bail him out, I know better and so all I can send him are words. And those are very difficult to choose.

Figure 7: This stock cut from the old metal type days captures how I felt the last few years in dealing with a troubled teen. Like a ton of bricks to the head!

Father/son coming-of-age advice has been coming down since the beginning of time, and I’ve tried to tap into the best of it, from Bruce Springsteen (“you’re born into this life paying for the sins of somebody else’s past”) to St. Louis IX (“love all good and hate all evil”). I fear not much of it is getting through, however, and Marc seems to be close to giving up on our relationship. So my time to make a point may be limited.

Figure 8: The Prodigal Son Returns, an engraving by Spada in 1844. One thing I’ve tried to make clear to Marc is that when he sets the right priorities, he’s welcome back.

Will I Look for the Same Things in a Woman That I Dig in a Girl?

In some ways, the definitions of what it means to reach manhood are pretty clear. Sociologists talk about the “big five” markers of adulthood: leaving home, finishing school, starting a job, getting married, and having children. And Jungian psychologists Sanford and Lough identify four dimensions of a young male becoming a man: finding a place in the social order, achieving financial independence, developing a social identity, and establishing a relationship with the inner self and the divine order.

By those definitions, Marc has a long way to go.

Figure 9: It’s hard to imagine most 18-year-olds being ready for adulthood. There are certainly days when I long for the innocence of a Chef Boy-Ar-Dee pizza and folk guitar, as shown in this 1965 advertisement.

Most cultures and religions have formal “coming of age” transition rituals that symbolically, if not actually, signal when a boy (or a girl) is to become a man (or woman). Marc has not had the benefit of any of these, other than the legal ritual provided by the state in the form of contractual and criminal responsibility, along with voting rights and the ability to buy his own cigarettes.

Figure 10: Another metal stock image cut, this one showing what it must feel like to be completely on your own with the burdens of life weighing you down.

In Japan, there’s a yearly national holiday on the second Monday of January where 20-year-olds celebrate becoming adults. There are ceremonies at which speeches are given, costumes are worn, and the whole thing ends up in a big party with lots of drinking.

Figure 11: In most cultures there is a close tie between adulthood and alcohol. In Marc’s case a big part of adult freedom is about the on-going party.

In Australia and New Zealand, a party known as the Twenty-First is traditional on that particular birthday, though now that most adult rights come at age 18, the event is moving up a few years.

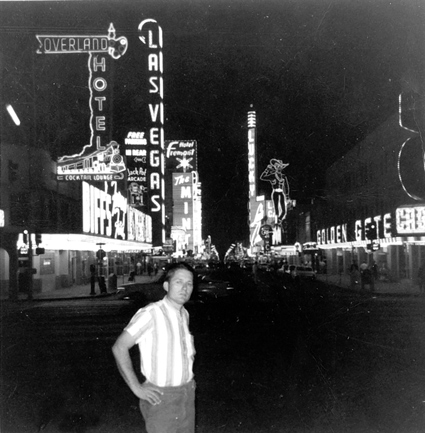

Figure 12: Becoming a man means being able to gamble and take other risks from which no one will protect you or feel sorry for you if you get stung. This 1964 snapshot is of an unknown man on his first trip to Las Vegas.

In many countries, including Spain and Switzerland, becoming an adult means compulsory military or social service of some sort, not a bad transition gimmick for those 18 year-olds still needing a bit of supervision before being set completely loose on society.

Many countries in the world associate adulthood with the right to drink alcohol and view and participate in pornography, the two most “adult” things about being an adult. Though in the end, the ability to enter in contracts is probably the most significant “right” of adulthood, as that becomes the foundation of most law.

Figure 13: These eight infallible rules are wise ones for anyone, especially a budding adult. Image courtesy of

Adgraphic’s Retro Ad Art Collection.

When you get into religious definitions, things are a little different. Catholics consider seven years old the “age of reason.” After that you can sin and go to Hell, so being able to buy a beer or look at porn may seem like a letdown by the time those things come around legally. Jewish boys become men at age thirteen, subject from that moment to the Jewish commandments. Mormon rules hold kids accountable at age eight.

Figure 14: St. Michael the Archangel slew devils at a young age. In the eyes of the Catholic Church, Marc has been an adult for some time. After the age of seven, that Church says your soul is subject to the same rules as everyone else.

Will I Settle Down Fast or Will I First Wanna Travel the World?

All kids have trouble taking responsibility for themselves, and most go through some sort of wild stage, either right away or later in life. It seems you can’t appreciate rules until you break them all at least once. For kids in relatively safe and secure environments, that can be done without a lot of consequences. But for kids on the streets, those mistakes often have very dire results.

Figure 15: I don’t know if these stock metal cuts really depict typical childhoods, but I do know that Marc never had a chance at being a normal kid. And while I want him to get a break, the past can’t be an excuse for current bad behavior.

What worries me most about Marc is not his survival — he’s a charming and resourceful kid when he wants to be. What concerns me is that he’s already getting jaded and beginning to accept his failures as inevitable. He’s been told many times in his life that he’s a screw up, and having been given up by two sets of prior parents doesn’t do much for his self esteem.

So Patty and I have been very careful to be consistent on at least two points, even if we botched plenty of others. First, we have always been clear that we are not Marc’s parents, even when we played a legal parent role. Also, we end every conversation with an open invitation to talk or visit again. Adopted kids classically test every relationship and do everything possible to sabotage them. Marc has done his best to sabotage ours, but if he thinks he’s been successful, then he’s not listening very well.

Figure 16: We made a lot of mistakes in parenting Marc, but one thing I think we’ve handled well is our open-door policy.

I think Marc cares for us beyond our ability to send money, something we’ll find out soon as we hold firm in our refusal to enable him any more. He will likely hit a pretty deep bottom before things get better, and I can only hope that bottom doesn’t include prison or a drug overdose.

Figure 17: Part of what makes a man, I think, is exposure to different places and cultures. One plus Marc has going for him is that he has lived in at least three countries and speaks two languages. That gives him a slight leg up on other kids making the transition to adulthood.

What Will I Be, When I Grow Up to Be a Man?

When Marc turned 18, I have to confess that I breathed a sigh of relief. Not because I think the drama is over (it’s not) or that Marc will have a happy life, but because I simply couldn’t handle the pressure of making decisions for someone else. I don’t know how parents do it day in and day out. I looked around and saw so much damage being done in the name of love and care that I had to second-guess every decision I made and every word I spoke.

Figure 18: In 1938 Progressive Pictures turned the tables and focused on “Delinquent Parents.” I won’t say we were saints in our role modeling to Marc, but we decided that honesty was the best policy, even when it may have sent conflicting messages.

Now at least Marc and I can talk “man-to-man” instead of parent to child. Unfortunately, after his brief period of freedom, Marc wishes he could go back to being the kid again, I’m sure. But, one of the measures of manhood is that there is no going back.

Figure 19: This stock image from the ComCut Company pretty much sums up Marc’s problems — he’s always wrestling with himself.

I feel like I’m at a new beginning myself, and for that I have Marc to thank. I learned that I am not God and that I’m not always right and that I can’t fix everything. I have more compassion now for others who tried their best even when it was misdirected. And perhaps most importantly, I’ve learned to keep my mouth shut and listen more.

So I’ve given up on trying to make a man out of Marc — he’ll have to do that himself. But I am glad to report that after 50 years, Marc has helped make a man out of me.

This article was last modified on May 18, 2023

This article was first published on February 12, 2007

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Chartwell Font Updated

In 2011, type designer Travis Kochel devised a very clever method of creating ch...

5 Great Script Fonts From Adobe Fonts

Need a great script font for use in your next InDesign project? Look no further!

Privacy Policy

Privacy Policy for CreativePro.com Updated as of November, 2007 CreativePro.com...