A Pre-Press Tutorial from PrintPlace.com

“Generally speaking, the term pre-press includes all the steps required to transform an original into a state that is ready for reproduction by printing. Pre-press includes the following steps: art and copy preparation (including typesetting), graphic arts photography (i.e., shooting negatives), image assembly and imposition (stripping) and plate-making. Depending on the nature of the original, other included aspects of pre-press may also include halftone photography, color separation or other procedures.”

GATF Encyclopedia of Graphic Communications, published by Prentice Hall

The quote above came from a 1000-page book considered by many to be the most complete text on the subject of graphic communications. For this tutorial, we’ll attempt to distill as much of this background as possible into a valuable, bite-sized piece that can guide Print Buyers through the concepts of pre-press. We’ll go over the basic workflow used in a typical pre-press division, whether the work is done by an independent service bureau or in the Pre-press department of a large printer.

We’ve seen different pre-press companies and pre-press departments at printers across the country, and for the most part the workflow is similar. Some of the independent pre-press companies have diversified and offered other services, such as video editing and Web site development. There may be varying equipment types from different manufacturers, or slightly different techniques, yet the workflow for pre-press in these companies is essentially the same.

Mechanicals

Printers use mechanicals to manufacture film that then become plates. Creating a mechanical can be done manually or digitally, by hand or on a computer. To create a mechanical by hand, artwork is assembled on acetate overlays positioned on art boards with instructions on where to place photos and color. The artwork is photographed using large-format graphic arts cameras, producing negative or positive film, depending on the printing process to be used. The film is “stripped” together so that the artwork is separated into correct colors. For example, if you are printing a newsletter and there are blue bars in the masthead, and the text and images print black, the bars are on one piece of film, and the rest of the artwork is on another. If the job is a four-color process color job (process is cyan, magenta, yellow and black ink – CMYK – printed at different densities to fool the eye into seeing the full spectrum of color) there is one piece of film for each of the four colors. There can be more than four colors in a job, but in all instances, each color is represented by one piece of film.

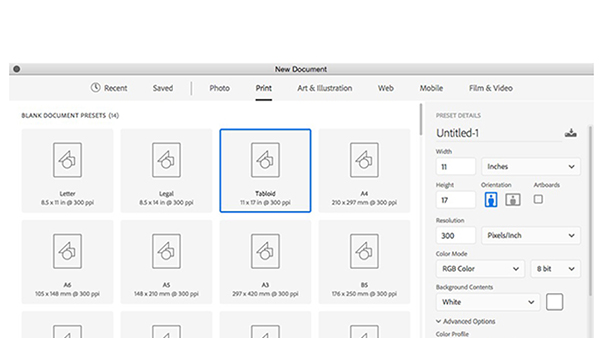

Mechanicals can also be created on a computer. Using illustration software like Adobe Illustrator™ and Macromedia Freehand™, complex logos and drawings can be created and saved as individual graphical elements. Continuous tone images can be digitized in a number of ways and also saved as individual computer files. Page layout programs like QuarkXPress™ and Adobe PageMaker™ allow you put all of the elements together. Type and simple graphic elements, like keylines and picture frames, are created in the page layout program and then the images and illustrations are imported and combined on the pages. The result is a “digital mechanical” that can be sent to a printer or pre-press company to be imaged to film or directly to plate.

Continuous tone images are either reflective copy (prints) or transmission copy (slides). Reflection and transmission are terms used to identify the process by which images are scanned or photographed in order to make negatives. Today, most images are scanned on digital scanners from slides, but more often, photographs are taken with digital cameras and transferred to the computer directly. Transmission refers to light passing through an image to the scanner optics, and reflection refers to light reflecting or bouncing back from an image to the scanner optics or camera lens.

Scanning

Scanning can refer to many processes, but here the term is simply defined as the process of digitally capturing reflective copy or transmission copy for the pre-press process. Images that are scanned require a lot of computer hard drive space, because scanned images are large files. An 8″ x 10″ image scanned at resolutions necessary for graphic reproduction requires about 40 megabytes of storage. If your project has many photographs, color and/or black and white, you may want to let the pre-press company or department scan them for you. Typically, they scan the images and provide them back to you on a disk or as proofs generated from film (or typically both).

If you send images, slides, or prints to a printer or pre-press company, it is important to specify the size and cropping information for each scan. If you have special instructions about color on a scan, you need to specify what the scanner operator should match because the developing process may produce color shifts. Professional scanner operators understand what you hope to achieve with your images, and can make certain your color concerns are addressed at the scanning stage-an experienced operator can take the slides made of the product and the actual product and make adjustments on the scanner, so the end result is a printed piece that will faithfully match the product you are trying to sell.

Imagesetting

Mechanicals created by hand are photographed in order to make film negatives or positives (depending on the printing process). Mechanicals created digitally are imaged on machines called imagesetters. An imagesetter is essentially a high-end version of the office laser printer. Both have computers to convert the digital information to plotting information, but an imagesetter will have resolutions as high as 5000 dpi (dots per inch) whereas the office laser printer might have resolutions up to 1200 dpi. There are two basic types of imagesetters, capstan and drum. With a capstan imagesetter, the media moves through rollers. A drum imagesetter keeps the material stationery while the laser assembly moves down a central axis to image the film. Imagesetters can have media (film, paper, or polyester plate) as small as 11″ wide and some imagesetter’s material can be more than 60″ wide.

Recently there have been great advancements in imaging technology and devices have emerged in the marketplace that will take digital files and image them directly to metal plates, bypassing the entire film process. There are many ramifications to this, particularly in proofing. Typically, a proof made from the film that is used to produce the plates is considered a very stable way to predict what will happen on press. Because going directly to plate bypasses the film stage, what does the customer use to anticipate what will happen on press?

When a printer or pre-press company produces a contract proof for the customer to sign off on, the company is saying, “what you see is what you get”-by signing off on the proof, the customer is agreeing to this shared understanding. However, if you image a proof from a file and then send that file along with the digital proof to be imaged again to metal plate at the printer, and if errors then occur while imaging the plate, you’ll have a good proof but a bad plate. If you don’t catch the mistake before the press run, you have a completed print job with errors. There are techniques, however, that will decrease your risk.

Direct to Plate

Many believe that the issues surrounding direct-to-plate are worth overcoming. The reason is that printing with digitally imaged plates produces higher quality printing than with plates exposed with film. If you take a page from a book and photocopy it, and then photocopy the copy, the quality of the copy becomes progressively worse. Great improvements in quality were seen when digitally produced film was utilized in the printing process, because manual stripping of film often involves many different layers and exposures. Each progressive exposure can degrade the quality slightly. Overall, digital plates produce better quality printing, and for this reason, overcoming the proofing issues is desirable.

Platesetters, like imagesetters, have Raster Image Processors (RIPs) that convert digital information to plotting information so that they can image the plate or film. The RIPing process is what usually introduces errors. Once digital files are RIPed, it is unlikely that errors will occur in the imaging. So smart providers are RIPing the digital files and imaging a contract proof, but keeping the RIPed file on the server until the customer approves the proof. Once the proof is approved, the same RIPed file that made the proof is imaged to metal plate. This is called “RIP once and image many.” If you’re producing work that will go directly to plate, this is an important consideration when choosing a vendor.

Editorial-Future Trends in Pre-press

If you have been in production for a long time, you will remember certain milestones in our industry like Postscript, and the first laser printer made by Apple. A personal milestone for me was when Photoshop had the ability to edit a CMYK scan from a high-end Hell drum scanner; and I remember when we learned how to create a drop shadow in an image in Photoshop. This wasn’t easy, given that the CPU’s on computers at that time ran at about 20-30 MHz, as compared to the 400 MHz speeds we see today.

The birth of new technology and the Internet is a milestone, not only for the pre-press industry, but also for many industries around the world. The Internet will allow us to address issues for printing that would be impossible without a global communications system. And as bandwidth increases, watch for software that will allow us to plan, organize and reduce the bureaucracy associated with today’s business.

I recently had lunch with the production manager of a large shoe manufacturer, and we were discussing life as a professional print buyer. At one point he said to me, “I just want to be able to efficiently produce whatever my designers can create, and not have to worry about everything else.” It is my goal to help him, and you, make that a reality.

About Richard Hawley

Charged with writing 1000 words about pre-press, Rick has had to distill 14 years of pre-press experience into a relatively small amount of space. Most recently, Rick was on the executive management team at a Portland, Oregon-based pre-press company, purchasing all equipment, hiring employees and designing the way the company performed their work for thousands of customers. Rick’s company has produced more than 30,000 pre-press jobs. Much of Rick’s professional and personal time has been spent staying abreast of the latest digital techniques for accomplishing the objectives of the pre-press industry.

Copyright 2000 PrintPlace.com, Inc. All rights reserved.

This article was last modified on August 8, 2000

This article was first published on August 8, 2000

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

How to Be a Better Designer: Learn About Type

Not everyone who knows about type is a good designer, but all good designers kno...

Using Photoshop Templates

Do you suffer from Blank Page Syndrome like I do? Instead of staring at the void...

Get Creative with This iOS 8 Keyboard

Why type your texts or use the same tired emoji icons in your emails when you co...