Scanning Around With Gene: Plane Spotting

I always wanted to be the kid in the back of the classroom who drew airplanes and tanks and soldiers instead of listening to the geography lesson. Instead, I was the one with my hand raised, and the closest I got to drawing was filling in little round circles with a yellow number 2 pencil.

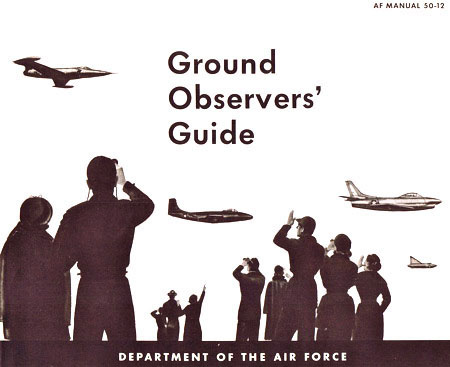

Yet we all grew up, even the kids drawing airplanes on the backs of Pee-Chee folders. I thought of those kids the other day when I came across a 1951 “Ground Observers’ Guide” published by the Department of the Air Force to help volunteer citizens identify and track potential enemy aircraft. Sorry for the bleed-through, but this booklet was printed on very thin paper. Click on any image for a larger version.

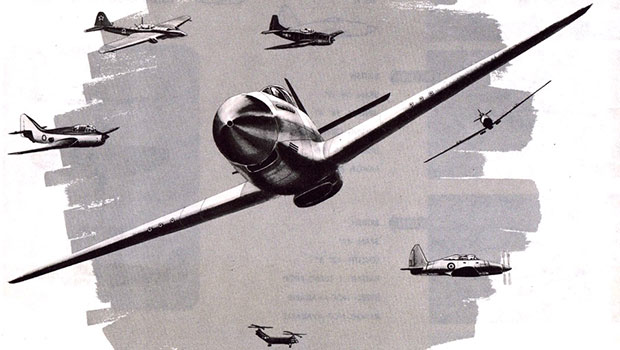

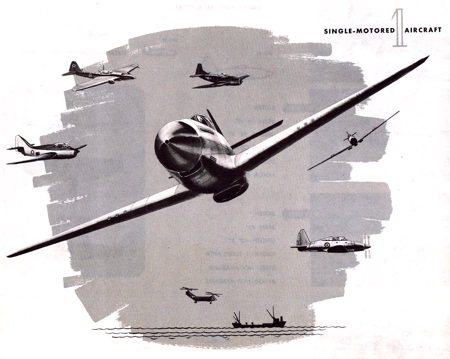

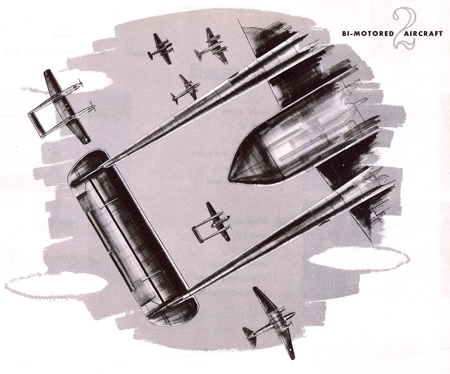

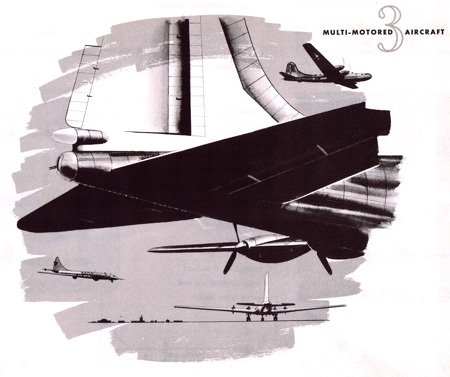

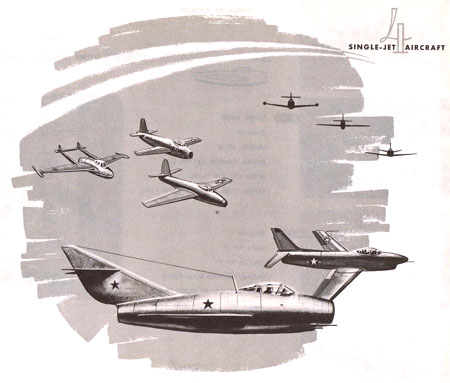

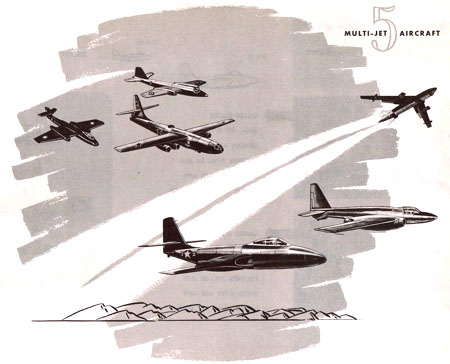

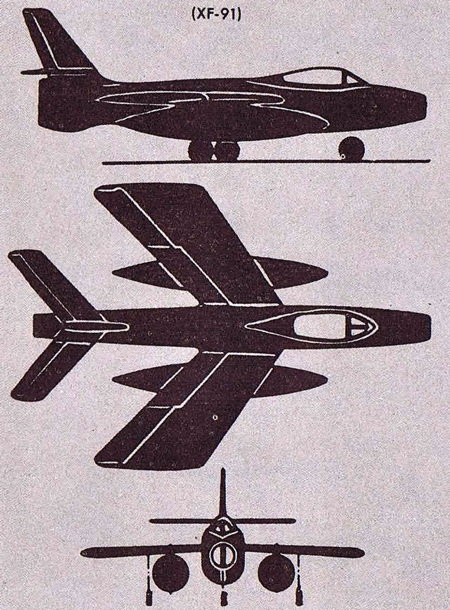

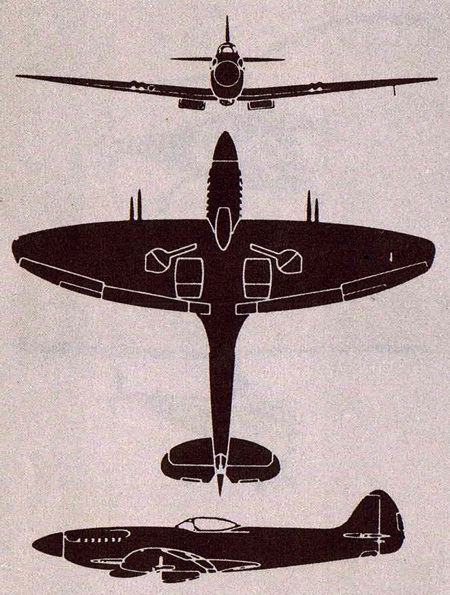

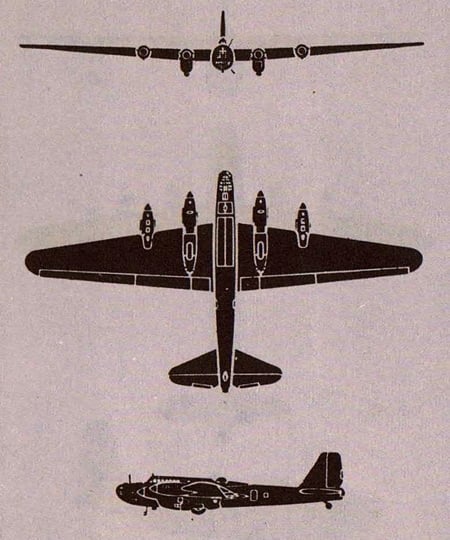

If you were a drawer of airplanes, this project was a dream come true. It has hundreds of illustrations of aircraft of all sorts, all drawn to scale from different views. And dividing each chapter is a title page with an air scene depicted in grayscale. Some talented Air Force artist goes un-credited for these, which appear to be drawn by one person.

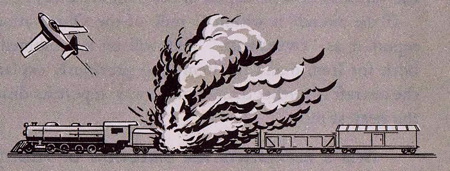

In today’s high-altitude, sophisticated radar world, you might not realize that at one time, citizen observers were the first line of defense from an enemy attack by air. And it was serious business. To quote from the introduction to this guide: “We are in a dangerous position. In a period of international strife and lawlessness, we stand as the bulwark of freedom. Every would-be aggressor knows that he can’t get by unless he defeats us first, for twice already — in two world wars — the tide of aggression has been turned by the weight of our industrial production. The next time an aggressor will certainly try to eliminate us first. He will strike first at our production plants and at the people who man them. What’s worse, he can do it!”

The text goes on to explain that the enemy can now strike us at any moment, even across great oceans. “Of course, the fact that we can hit him far harder than he can hit us should stop any enemy,” the booklet says. “We have far more atomic bombs. Yet the enemy might decide to make the desperate gamble.”

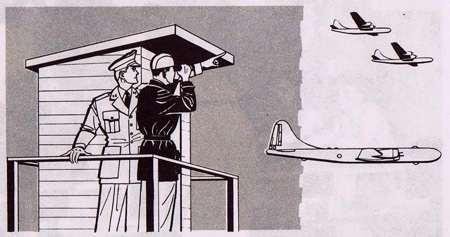

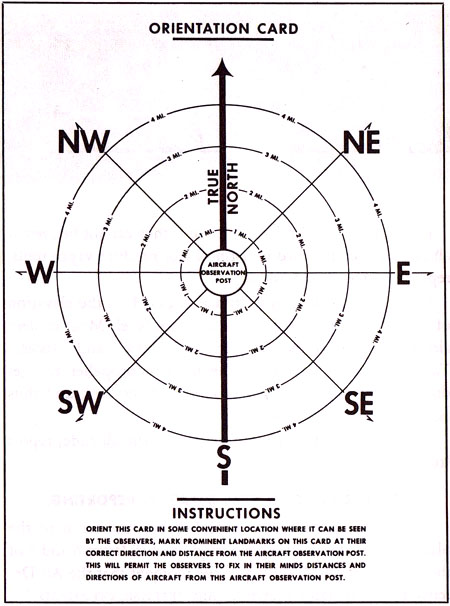

This is where citizen observers came in. There was an elaborate network of observation stations and local observer groups, and a protocol for reporting aircraft to a central tracking station in Colorado. You were expected to take your duties seriously and reporting aircraft sightings immediately.

“There is little probability of turning back an enemy air attack completely,” we discover from the booklet, “however, if we have adequate warning, we can destroy or turn back a large number of his bombers and reduce considerably the losses that the rest might cause. The big problem is adequate warning.”

So for many years, observers reported regularly to their posts and watched the sky for any sign of activity. All aircraft were to be reported. It wasn’t up to the observer to determine if it was an enemy aircraft, only that it had entered into view.

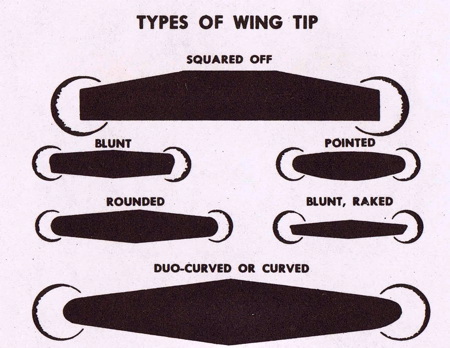

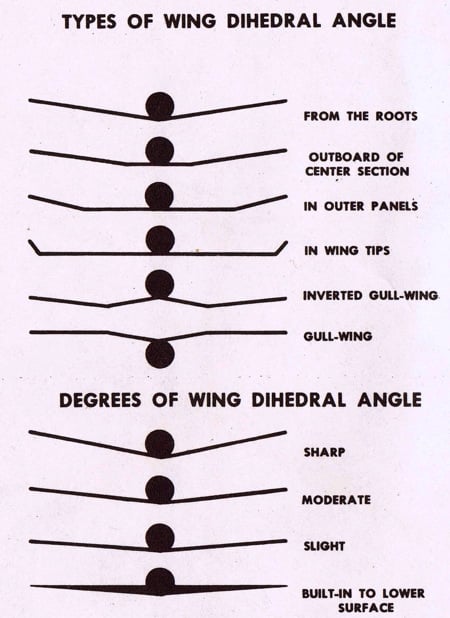

“Ground Observers’ Guide” was the bible of the ground-observer corps and served as a reference manual on all things aircraft-related. There were propeller craft, jet aircraft, single engine, and multi-engine planes. There were all sorts of wing configurations, tail designs, and wing positions. Anything that could be differentiated was drawn for a layman to understand.

I hate to be sexist, but I’m going to speculate that the artists who drew this booklet were all men, if for no other reason than the Air Force was probably all or largely male back then. And I don’t remember a lot of girls in the back of the classroom drawing tanks and planes. I think they were drawing horses.

I love that this booklet exists because it means that at least one of those kids back in the fourth or fifth grade grew up to do exactly what they wanted to do back then: draw airplanes. And here I am still trying to figure out how to put those geography lessons to good use.

This article was last modified on May 17, 2023

This article was first published on June 4, 2010

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Adjust Word Spacing in Paragraph Styles

MH wrote: We are doing a series of children's books and ample space in between w...

Rein in Rogue Leading

Do the last lines of some of your paragraphs sometimes refuse to follow orders,...

Linotype Releases New Fonts in January

A new year is here, time to get back to the drawing board. Linotype has been bus...