Scanning Around With Gene: Our Love/Hate Relationship with the Atom

Most adults above the age of about 45 probably remember having atom-bomb drills at school and being taught that the best chance of survival in a nuclear holocaust was to “duck and cover” under your school desk. At the same time, teachers were also doing their best to teach young Americans that the atom was our friend and, in the right hands, was not something to fear. The mixed-message of atomic power lasted until about the end of the 1960s, when it finally began to sink in that preparing Americans for nuclear attack was a futile and unrealistic exercise. But for a while the atom in all its form was a regular topic of discussion, worry, and even opportunity.

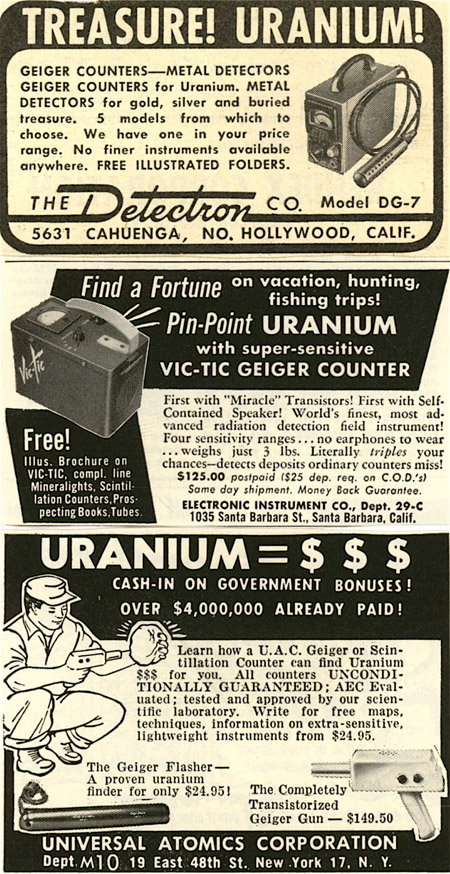

After the Soviet Union tested a nuclear weapon in 1949, the United States government went on a uranium-buying spree, which created the first wave of atomic opportunity. In 1951 the Atomic Energy Commission became the sole legal buyer of uranium ore in the United Sates and offered double the usual rate for miners who discovered uranium deposits. Most uranium is in Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico in prehistoric streambeds, where fossilized trees become radioactive over the centuries. Thousands of individual miners set off in search of uranium using hand-held Geiger counters, such as those advertised here.

Like all mineral rushes, a few people made good money hunting uranium and others went bust. Throughout the ’50s and early ’60s, however, prospectors combed the Colorado Plateau digging and drilling for “atomic gold.” It wasn’t until later that miners started dying in large numbers from lung cancer and other radiation-induced ailments. In uranium mining areas it was not unusual for people to place a chunk of uranium in a pitcher of drinking water to bring about miracle cures. Watch dials were painted with radium to make them glow in the dark, crocks and mugs were made from radioactive materials and sold as healthy kitchenware. Little was known about the dangers of handling low-level radioactive materials. Many people felt that if it existed in nature, it couldn’t be harmful.

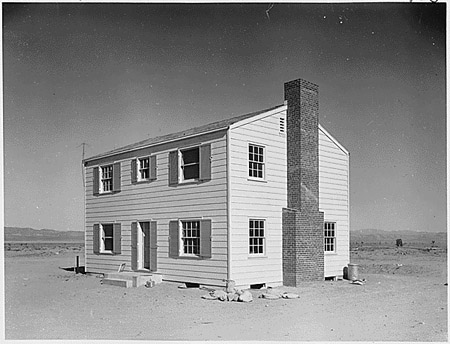

As the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union escalated, the “wonder” of nuclear energy turned more and more toward fear. Testing of nuclear weapons started to show the sort of damage that could be expected in any sort of nuclear combat. These pictures from a 1955 test in the Nevada desert show a before and after picture of a farmhouse 5,500 feet (that’s more than a mile) from the center of a relatively low-level blast.

So the United States began to prepare the citizenry to the possibility of a nuclear attack. A nation-wide system of bomb shelters was set up, and all major cities installed air-raid sirens that would alert the citizenry of a coming nuclear attack. In my town these sirens were tested once a month. We would practice drills at school, always aware that before exiting the building we should line up in height order, presumably so it would be easier to identify our charred bodies later. This 1951 booklet was distributed to teachers in the Los Angeles School district to educate them on the threat of nuclear attack.

The booklet goes on to give this great advice, which includes wearing long-sleeve shirts to minimize burns. And if you think the response to hurricane Katrina was muddled, imagine the response to a nuclear attack from the people listed in the “Civil Defense and Disaster Relief” org chart below. Very reassuring to teachers, I’m sure.

But the real threat and fear came in 1961 during the Cuban Missile Crisis (where it was discovered the Soviet Union was placing nuclear missiles in Cuba, close enough to strike the United States). President John F. Kennedy went on television and advised Americans that they should, among other things, consider building their own fallout shelters to protect themselves from nuclear radiation after a blast. This 1961 record album outlined some of the steps people were advised to take in preparation for the inevitable.

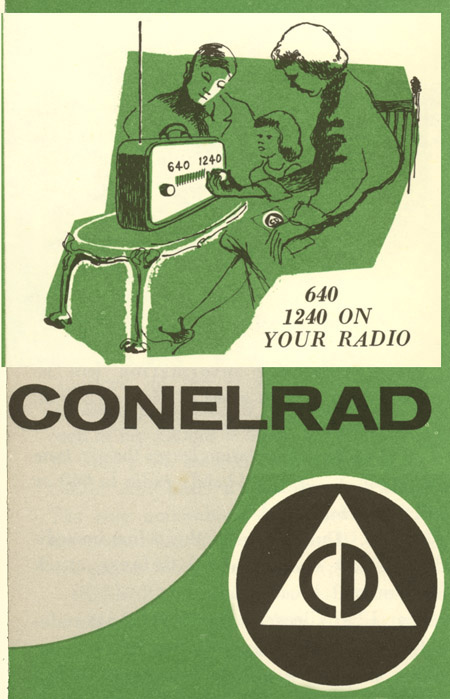

Conelrad, short for CONtrol of ELectromagnetic RADiation, was set up as a nationwide radio alert system and everyone was taught to turn their radio dial to either 640 or 1240 AM for nuclear attack news. Additionally, a standard system of warning signals was worked out, as shown below.

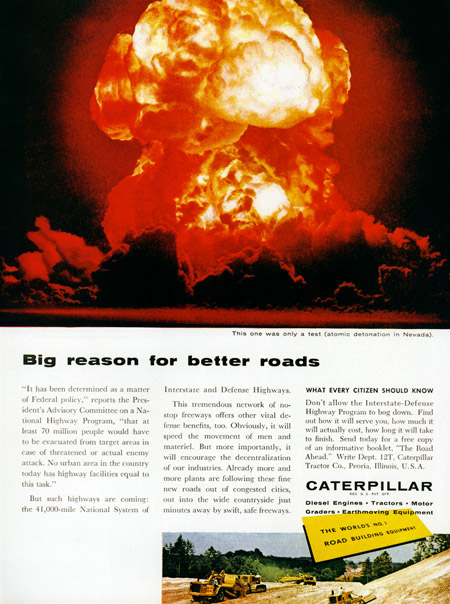

The threat of a nuclear attack was strong enough for advertisers to take some advantage of it, as shown in two interesting cases below. The first ad, from the Portland Cement Association in 1955, suggests that a house made of concrete will be more “blast-resistant.” The ad goes on to say that such a house could protect the occupants at distances as close as 3,600 feet from ground zero with a bomb force equivalent of 20,000 tons of TNT.

The second ad, from Caterpillar, is from 1958 and states that in the event of a nuclear attack, as many as 70 million people may have to be evacuated from major cities. This would, as you may expect, put a tiny bit of stress on the national highways and roads. So Caterpillar suggests building better highways as part of our national defense efforts.

And while I don’t think many people built fallout shelters, many people thought about it, and a small industry was born almost overnight. At my house we started digging a big hole in the backyard but only got about five feet deep before giving up. Here, in 1962, a Life Magazine cover talks about public shelters, and goes on to show examples of how some families were dealing with their own shelter efforts.

Go to page 2 to learn who would be allowed in Gene’s family fallout shelter after the Big One Dropped.

This article was last modified on May 18, 2023

This article was first published on October 3, 2008

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

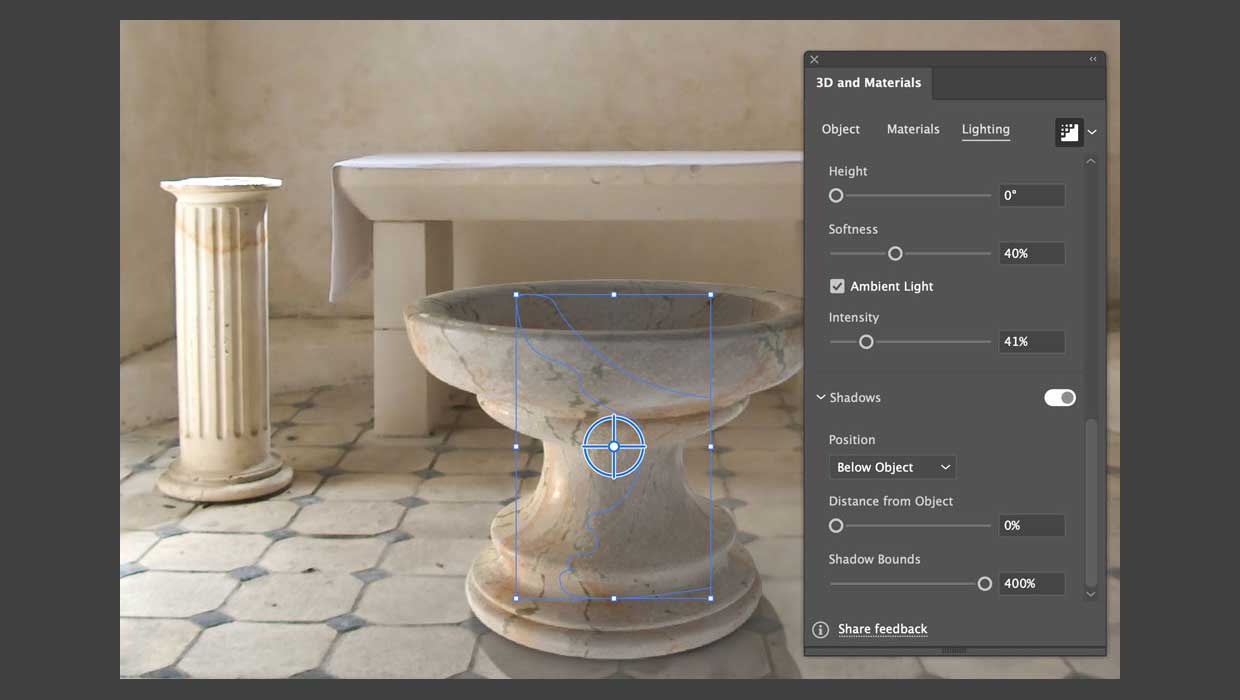

How to Build a 3D Object in Illustrator

Learn how to apply materials and lighting to a simple vector drawing to make a r...

Top Tips for Photoshop Book Now Available!

Twenty of our most popular Photoshop tutorials curated and collected in a conven...

First ClearType Font Pack for Microsoft Office Released

Ascender Corporation today announced the release of its first retail font softwa...