Around the World in ePublishing with Pariah Burke: Adobe Illustrator: The Early Years

Each installment of Around the World in ePublishing looks at a different digital publication—sometimes an ebook, sometimes an etextbook, sometimes a digital magazine or catalog. With each publication we’ll examine the techniques and technologies used, the good and bad choices the designer and publisher made, and sometimes even how to incorporate the same features and effects into your own publications.

This time we’re looking at Adobe Illustrator: The Early Years.

What Is It?

One-off iPad app built using InDesign, Adobe DPS, and a special HTML5 JavaScript library.

Authors: Ton and Hans Frederiks

Publisher: Three Publishers B.V.

Published: December 2012

Cost: Free.

Get it: Here.

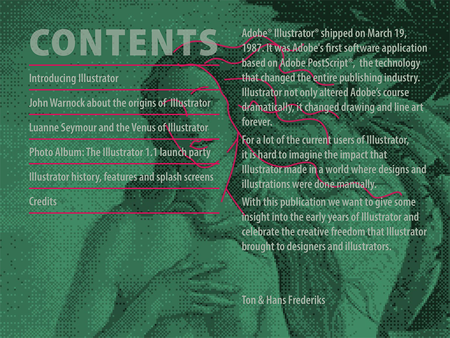

Adobe Illustrator: The Early Years is a one-off Adobe DPS-created publication celebrating the 25th anniversary of Adobe Illustrator. Illustrator was the first application Adobe created, and it was the first application to offer precision illustration abilities on a computer. The creation of Illustrator transformed Adobe from a systems creator into an application publisher, and lead to the vast stable of Adobe applications on which we creatives now rely. Adobe Illustrator: The Early Years, is a brief insight into the beginnings of this game-changing and beloved drawing tool through prose, audio, video, and touch interactivity.

The Good

Very little of Adobe Illustrator: The Early Years is original material—but that’s a benefit, not a drawback. Comprising the majority of the publication are articles, insights, images, and video previously published elsewhere from those who were there at Illustrator’s beginnings.

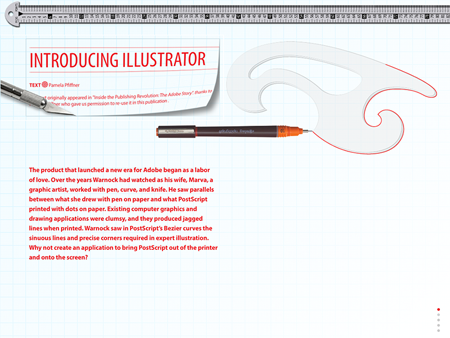

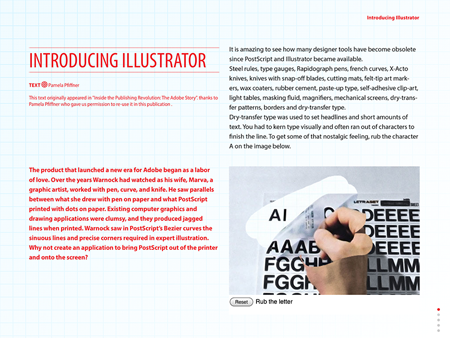

The narrative starts with the article, “Introducing Illustrator,” originally published in the excellent hardcover book Inside the Publishing Revolution: The Adobe Story, written by Pamela Pfiffner. The reprint isn’t a mere duplication of the original’s layout, however, as so many burgeoning digital publishers feel constrained to imitate. Designers Ton and Hans Frederiks included the prose, of course, and several of the photographs from the 2003 original book, they took welcomed liberties with the layout, incorporating photography and illustration not in the original. Even better, the Frederiks took advantage of the digital magazine medium to go beyond what the original book could have included. For example, on the first screen of the piece several images come and go to be ultimately replaced by an interactive feature that lets your finger burnish rub-on lettering onto a page (see Figure 1 and 2).

Figure 1: The imagery on this page changes over the course of a few seconds.

Figure 2: Have a little patience and you’ll be rewarded with the sidebar and interactive rub-on lettering feature.

The third screen of the “Introducing Illustrator” piece features a video news report from the 1987 Macworld Expo at which Adobe debuted Illustrator.

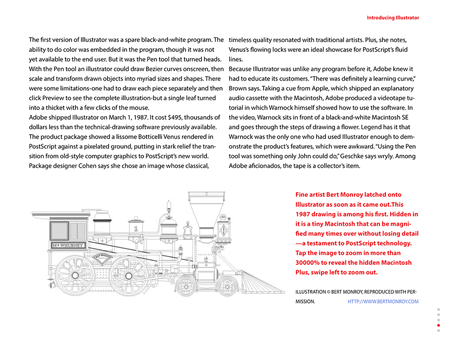

The fourth screen, then includes the famous drawing created by Bert Monroy, a train steam engine (see Figure 3). Hidden within the train is a drawing of a Macintosh Plus, which is only visible when zooming to 30,000% on the train. Although Bert’s drawing has been featured in numerous publications over the years, this is probably the first time it was presented in such a way that readers can actually perform the zooming live on the publication page; a tap on the steam engine zooms the illustration in to the Macintosh Plus while a simple swipe zooms back out.

Figure 3: Bert Monroy’s famous PostScript steam engine (with hidden treasure) illustration demonstrating the resolution independence of vector drawing.

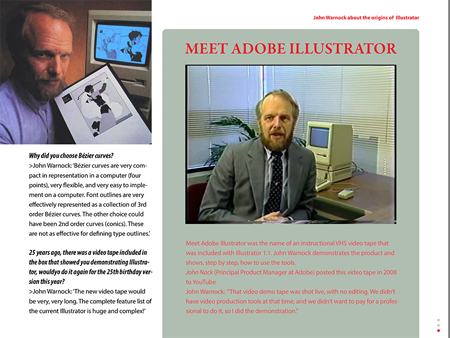

The excellent use of interactivity continues throughout the remaining four features. In the “John Warnock about the origins of Illustrator” piece, for example, the authors have embedded the video Adobe CEO John Warnock produced as an instructional VHS in the Illustrator 1.1 box (see Figure 4). The video is an important piece of history for those of us who are fans of Illustrator, Adobe, or the Desktop Publishing Revolution as a whole. In it John, the father of Illustrator and, according to legend, the only person at Adobe who understood the use of the Pen tool enough to demonstrate it, shares the passion that lead to the creation of Illustrator. The very 80s art video music introducing John’s video is also used within the cover of Adobe Illustrator: The Early Years, invoking nostalgia from the moment the app is opened.

Figure 4: An embedded video overlay brings the most famous and rarest piece of Illustrator nostalgia to everyone.

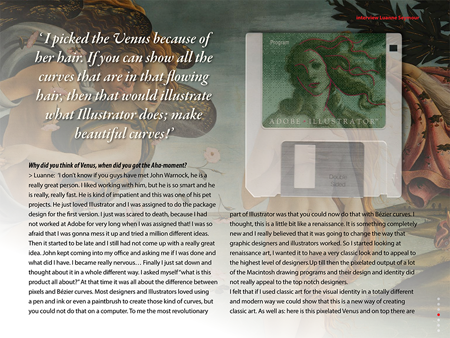

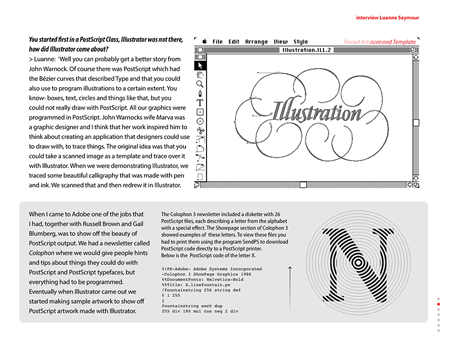

In the next article the Frederiks interview Luanne Seymour, the person who gave Illustrator its unmistakable branding, Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (see Figure 5). Throughout the seven-screen article static and interactive elements are incorporated brilliantly to enhance and punctuate the compelling interview. I particularly like the way the slideshow overlay and the scrolling text frame work together in the sidebar on screen two (see Figure 6).

Figure 5: When Venus became the symbol of Illustrator.

Figure 6: A scrolling text frame of PostScript code and a slideshow enhance this sidebar about the Adobe Colophon newsletter, published to show off the capabilities of Illustrator

Adobe DPS can do a lot with photographs with and multi-state objects, but something DPS can’t do natively is allow readers to move objects arbitrarily around the screen. Instead of living with that limitation, the authors turned to the Hammer.js multitouch JavaScript library. The fourth interior article in the book is an HTML5-based article utilizing Hammer.js to enable readers to explore, move, re-order, and rotate eight photographs as separate objects (see Figure 7). Tapping the top photograph and dragging it with a single finger moves the photo around on the canvas. Tapping and dragging a photograph behind the top one moves the selected image to the top of the stack. Resizing images is accomplished with the familiar two finger pinch-and-pull to zoom actions. Dragging an image with two spread fingers rotates that image through a full 360 degrees.

Figure 7: A JavaScript library added to an HTML5 article enables readers to move, rotate, and resize these images on the page.

The splash screens gallery is another very nice feature (see Figure 8). It’s a simple multi-state object showing the succession of Illustrator’s desktop splash screens from version 1.1 through CS6 (version 16). As each splash screen image changes so does the descriptive text at the bottom revealing that version’s year of publication, its codename, and the new features it brought to vector drawing. The splash screens rotate automatically at five second intervals, with manual swipes across the images, or in response to taps on the MSO thumbnails along the right.

Figure 8: MSOs enable readers to explore the splash screens, codenames, publication years, and new features of every version of Illustrator from 1.1 through CS6.

A Credits page caps off the publication with good information—except as discussed in “The Bad” section below—complete with hyperlinks to sources, a nicety often lacking in one-off digital publications.

The Bad

The lack of paragraph separation is vexing. As you can see in Figure 9, the designers neither indented the first line of new paragraphs nor included vertical spacing between them. Instead, they relied on the natural white space left in the last line of preceding paragraphs to create separation. Sometimes that was almost sufficient, sometimes it wasn’t.

Figure 11: Legibility on the Contents page is improved but not ideal.

On the whole, people dislike being misled into thinking that a work in progress or beta product is the final version. Even though the authors’ intent was to encourage readers to hang onto the app and wait for future updates, the opposite will likely occur. This is especially true if the updates never come. I write this review four months after Adobe Illustrator: The Early Years was published, and it has yet to be updated. Perhaps it will be when Illustrator CS7 is released.

Neophyte self-publishers often fall into the trap the Frederiks created with that Credits page note, and that’s unfortunate. For one reason or another, the self-publisher finds it necessary to publish the material in a form the author feels is incomplete. Sometimes that’s a technology issue—i.e. the self-publishing author wants content to do something the technology won’t allow it to do or he can’t figure out how to make the technology do—and sometimes, as in this case, it’s a matter of unfinished or omitted planned content. When publishing something that isn’t exactly what he planned, the self-publisher feels the need to tell the audience how great the project would have been had it been complete. I call upon self-publishing authors to resist that urge. Giving in to it merely takes what might already be a great project and diminishes it.

If you can’t publish exactly what you want, look at your options:

- Wait until you can publish the complete project, with the functionality desired.

- Publish it as is and let it stand on its own. It might be better than you think even with those missing pieces.

- Publish the project as is and update it later. It’s not at all uncommon for book and periodical publishers to publish corrections, clarifications, and updates as needed. To wit: A layout error caused a table in my recent book, ePublishing with InDesign CS6, to go to press incomplete. Once I recognized the error I published the complete table as a PDF correction to the book on my Website.

- Publish the project as is, letting it stand alone, and then publishing the missing or incomplete elements later as their own projects. To again point to my own work in this regard, because of page count restrictions on the printed book, my publisher elected to cut large sections from ePublishing with InDesign CS6. I then expanded those cut sections into their own books and teaching materials, the first of which is my self-published Creating Fixed-Layout eBooks (The ePublishing with InDesign Series).

Final Word

Despite the design mistakes, which are mostly concentrated on the Credits page, Adobe Illustrator: The Early Years is a publication that belongs on your iPad. If you’re a fan of Illustrator or the Desktop Publishing Revolution, the book, though thin, contains lots of historical imagery, video, and commentary from the people who were there during the early years of Adobe Illustrator. For those producing digital publications for themselves or others, this scant 138 MB book is a beautiful example of digital publication layout and restrained use of DPS overlays.

For both reasons it has certainly earned itself a permanent place in my collection, right alongside—figuratively of course—my autographed copy of Inside the Publishing Revolution: The Adobe Story.

Let Me Feature Your ePublication

Do you produce electronic publications? If so, I’d really like to see them for possible profiling in “Around the World in ePublishing with Pariah Burke.” I’m interested in any type of modern electronic publication built as EPUB, KF8, MOBI, PDF, digital replica, or interactive tablet publication. Please send one or more examples of your publication—or URLs thereto—to *******@*******ah.com?subject=ePublishing%20World%20Example%20Submission”>ep*******@*******ah.com.

This article was last modified on January 18, 2023

This article was first published on April 8, 2013

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Sharpen Focus with Photoshop’s Auto-Blend Layers

This tutorial is courtesy of the Russell Brown Show. There are times when low li...

Raise Image Resolution Directly in InDesign

What do you do if you have dozens of images in InDesign and your printer says th...

Hail to the Glyph: Hillvetica is a Typeface with Presidential Ambitions

Hillary Clinton’s announcement that she was officially running for Preside...

is troubling (click to zoom image).</em></p>

<p>And that leads into the discovery of the second typographic problem. As you can see in Figure 10, widows aren’t uncommon. Remember that Adobe DPS publications are, like PDFs and print output from InDesign, WYSIWYG. Unlike EPUB, HTML5, and similar adaptive formats, text on the page won’t reflow in response to the device resolution and viewport. Those widows you see in the app are in the InDesign file as well. They should have been fixed.</p>

<p><a target=)