Under the Desktop: A Creative Pro Looks at Linux

Walking the aisles of last week’s LinuxWorld conference and expo, I checked out some of the latest and greatest Linux applications and hardware. While a small show, taking up just one hall of San Francisco’s Moscone Center complex (and the smaller one at that), on display were plenty of blade computers (thin, pizza-box-style servers that are made to fit into racks), big storage systems, and a panoply of server and database applications. But for all my searching on the show floor, I found but two demonstrations of digital imaging applications, and one of them was Adobe Photoshop, which doesn’t come in a Linux version.

I shouldn’t have been surprised,, I suppose, but as Linux is being touted as an inexpensive "open" alternative to operating systems like Windows and the Mac OS, I wondered.

The Likable OS

A variant of Unix, Linux is a powerful operating system that’s been in development for decades and used by a wide range of computers, from mainframes to desktop systems. For example, Unix is the foundation of Mac OS X, and versions of it have been used by many companies such as Hewlett-Packard Co., IBM, Sun Microsystems, and SGI. These companies have separate versions of Unix, which support their own processors and graphical user interfaces.

About 12 years ago, a Finnish programmer named Linus Torvalds developed a version of Unix as a hobby and put it out for use by the worldwide community of programmers. Developers can use Linux as a platform for their applications or extend features of the Linux OS itself.

Some programmers have formed ad hoc "projects" aimed at improving a particular function or compatibility of Linux (such as support for processors and other hardware), or developing applications (such as for graphic imaging). Many programs are free, since the community picked up on principles advocated by the Free Software Foundation or the GNU Project, yet another free version of Unix. All of these applications are based on that powerful foundation and are often less expensive than the usual commercial product, or even free. And there’s a community and culture surrounding the OS that can beat that of the Macintosh. (Linux Online offers a good set of articles and links about Linux.)

So I wondered: Given this showing at the tradeshow, is Linux really a viable platform for professional content creation? Or perhaps might a designer be wooed to ditch working with the established operating systems: the classic Mac OS, Mac OS X and Windows, and move over to Linux?

The answer might be difficult to find at last week’s show, which focused almost exclusively on enterprise and Web servers and database applications, the current primary markets for Linux. And there was some evidence of desktop productivity applications. Still, LinuxWorld is supposedly all about Linux and some folks might expect some appearance of content creation applications.

But no.

At the same time, despite their negligible numbers, the imaging apps on display at LinuxWorld revealed quite a bit about the direction of the platform.

On the Right Track?

One of the applications on the floor was Cinelerra NLE, an editing and audio/video effects package for high-definition television from Linux Media Arts Inc. (see Figure 1). It was demonstrated in Advanced Micro Devices’ booth running on the company’s 64-bit Opteron processor.

The real-time effects package supports unlimited audio and video tracks and a bunch of interesting features. It works with the company’s Open HD server, which can import and export a wide range of raw high-def formats and supports the Material Exchange Format (MXF) standard. MXF adds a metadata wrapper to streaming content, much as XML provides a structure for more static data. (Here’s some more detailed discussion from Video Systems magazine.)

Figure 1: There’s a timeline and multiple windows, so we must be in a video editing applications. In this case, it’s the Linux-based Cinelerra. The right hand window shows its digital slate generator.

According to Linux Media Arts’ CEO Michael Collins, the company began by creating OEM drivers for high-end video cards used in film and broadcast production and then branched out with a variety of products, including servers and software. Now, he said the company hopes eventually to take away some business from industry leader Avid Technology.

Collins said a number of his current customers require custom digital controllers for proprietary legacy systems still in use in Hollywood. Linux provides a good base for that development.

"Artists, not engineers, make movies," Collins said. The studios continue to stretch out the use of equipment, some decades old, because of the artistry of individuals using the tools. Conversely, his small development effort can quickly create custom tools and effect plug-ins requested by studios as well as individuals.

Linux’s Photoshop Connection

The other stop-off point for content creators at LinuxWorld was the Wine booth. This Open Source project doesn’t have any innate graphics abilities, rather it’s a good neighbor to non-Linux applications.

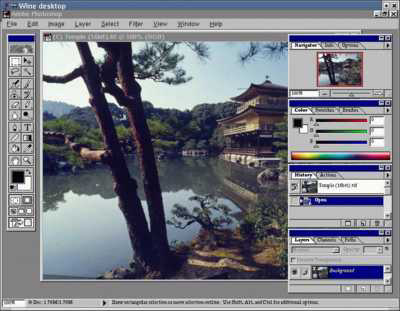

Wine is a Windows emulator for Linux and several other Unix environments. Like Microsoft VirtualPC for Mac, Linux users can use Wine to run useful Windows programs, in this case Microsoft Office and Adobe Photoshop (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: If you squint, this program is familiar enough — maybe it’s the haircut that’s different. Instead, it’s a copy of Adobe Photoshop for Windows running on the Wine emulator for Linux. Go figure.

According to online postings, the Wine emulator offers better compatibility with Photoshop 5.5, although some folks have made Version 6.0 work. However, Crossover Office 2.0, a commercial emulator from CodeWeavers Inc. supports Photoshop 7.0. CodeWeavers contributes routines to the free Wine effort as well.

Now, why would we ever want to do this, some of you might ask? This is the usual question asked when considering emulation software. Obviously, the best compatibility and performance is always available from a workstation running a native operating system; either one OS or the other but not one on top of another.

One answer is the bottom line, according to an interesting eWEEK article covering the move to Linux by Disney’s feature animation department. Most users in the group now run on a Linux desktop, while some machines run Sun Solaris and Mac OS X.

However, the department still had more than 200 users who needed to use Photoshop on a regular basis in their workflows. As with the customers supported by Linux Media Arts’ tools and drivers, Disney recognized that these content creators do their best work (and work best) with Photoshop. It’s the tool they’re used to, so the company found a way to maintain these creators with their familiar tools.

Disney could have purchased Windows workstations for these creators, but that would mean both additional hardware and software expenditures beyond their Linux machines. Instead, Disney decided to run the Windows software with the Crossover Office emulator (actually, they spent a bunch of money to get Crossover Office to fully support Photoshop).

According to the article, Disney IT managers calculated that the Linux emulation offered greater savings when adding in the cost of Windows licenses and the extra support costs for the Windows machines. A manager said the Windows machines will all the licensing would come to $50,000 as well as additional annual support costs of $40,000 a year. Instead, the cost of the Wine emulator and licenses cost about $15,000.

Certainly, given the worldwide problems this week with the Blaster Worm on the Internet, it’s easy to understand how an IT support organization could appreciate a Linux-based workflow. The worm exploits a security hole in Windows and has been completely clogging local area networks and even entire parts of the Internet with bogus traffic. Information about the problem and a patch is available from Microsoft. Networks with even a single Windows machine can be vulnerable.

Looking for Linux in all the Wrong Places

Wiser heads in the industry would simply point out that instead of my asking "where have all the content apps gone" at LinuxWorld, I should have been looking elsewhere. I was looking where the spotlight was brightest at the moment — even though it was a Linux tradeshow. But last week’s show just isn’t the right one for content applications.

Applications in the scientific visualization market as well as in the movie industry have migrated from using plain Unix applications on specialized workstations to Linux versions running on mainstream hardware platforms. Shows like SIGgraph (held in San Diego in July) and the National Association of Broadcaster’s NAB conference (found in Las Vegas in April) are more likely locations.

Most of us are familiar with some of the streaming content creation applications on the Linux platform, including Alias Systems’ Maya, Avid Technology’s SoftImage line, and Pixar’s Renderman. If you don’t recognize the products themselves, you’re no doubt familiar with their images in the movie theater or on television.

Each one is a platform application in its own right, and most of the titles have a bevy of plug-ins and modules. Besides, they’re not just on Linux, most of these applications come in Windows versions and some support OS X.

Well-known in the open source community is the film imaging application CinePaint. The software supports high-resolution images and 32-bit color required for the movies and was recently used to retouch parts of several feature films including the Harry Potter series. The program is available in Linux, OS X, and Windows versions.

Figure 3: Here’s a screen shot of the new Mac OS X version of CinePaint. It’s been used for a number of Sony Pictures Imageworks productions.

Of course, there are professional-level content creation applications outside the film industry and scientific markets. One well-known Open Source project is GIMP, a general-purpose drawing and image editing application with tools that would be familiar to users of Photoshop (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: This anime illustration was created in GIMP by Marco Lamberto. His site, called The Sunny Spot, discusses GIMP and Japanese anime and manga.

Gathering Linux Resources

Still, the experience using these Linux applications would be different for an individual or a small company than it would be for someone inside a large company with greater resources. Unlike OS X or Windows, the Linux content market is very small and there can be gaps in software and system level support for peripherals and certain system resources.

Take for example the response I received from Robin Rowe, the CinePaint project leader and Linux consultant, about a question on color calibration on Linux.

"The studios had already mastered color on Unix, then ported to Linux," Rowe said. "Comparing companies like DreamWorks, with more than a hundred Linux programmers on tap just at their Glendale studio, to other industries is no comparison. The studios have much more technical depth than most people imagine. You can rest assured that DreamWorks and other studios have Linux color calibration. Where tools are missing they simply build something better."

Perhaps I would rest assured if I was a big Hollywood studio. However, if I’m a individual content creator … ? There are several different color-calibration packages at different price points for content creators on Mac and Windows systems. And this is just one product category among the many hardware and software technologies that you use in the course of a job.

From my vantage, the Linux market relies on loosely organized projects to accomplish some big tasks and then fills in the holes with custom programming. That business model may work for you, depending on your need or whether your primary occupation is in the film business. But at this time, that practice could prove difficult for creators of other types of content.

As it is said: "Nothing is difficult — if you only know how." With enough practice, exploration of tools and perhaps some reaching into the pocket for a bit of custom programming, Linux might fit your workflow.

Read more by David Morgenstern

This article was last modified on January 3, 2023

This article was first published on August 14, 2003

Commenting is easier and faster when you're logged in!

Recommended for you

Easy Diacritics and Other Tough Glyphs

In an earlier post I presented a workaround for entering non-native language dia...

InDesign New Features Guide Updated for CC 2015.1

James Wamser has updated his indispensable InDesign New Features Guide so it inc...

Mirroring Vertical Ruler Guides

The layout I most commonly use is one for facing pages, where the settings on th...